And so the first question that the priest asked —

the first question that the Levite asked was, “If I stop to

help this man, what will happen to me?” But then the Good

Samaritan came by. And he reversed the question: “If I do

not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?”

That’s the question before you tonight.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. died on April 4th 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee. I recall the fear I felt, and my parents discussed openly when hearing the news. Detroit had riots in July of 1967 that were fresh in my memory. And on March 14th—just three weeks before he was assassinated—Dr. King had spoken at the high school that I would attend a few years later. We deeply feared that riots in Detroit would resume on that night.

What was also ignited in those three weeks and the news of assassination was an intense curiosity within my spirit. I wondered why this man, who spoke of nonviolence, was so violently murdered. I wondered why someone would kill him. I wondered why my city was a cauldron. The fear of those moments propelled me to explore. To listen to the recordings of Dr. King’s speeches, some of which were released by Motown Records.

Years later at M.I.T. I had to choose my minors to supplement my engineering degree. I chose creative writing and spent four semesters reading and writing about the work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

I came to understand that Dr. King’s focus and agenda in the last years of his life had widened to address deeper and larger structures of American society, and that he focused on militarism, racism and materialism. He zeroed in on the importance of economics.

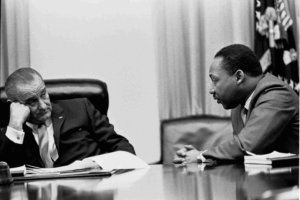

I went on to become an economist and, when working in Washington D.C. at the Senate Banking Committee, I became friends with the great political writer William Greider who was working on his book Secrets of the Temple about the Federal Reserve and U.S. politics. Bill interviewed Dr. King’s son Martin Luther King III for Rolling Stone magazine. And this is what Dr. King’s son had to say about his father’s death.

And then Daddy comes out in 1966 and attacks his (LBJ’s) stance on the war. Well, that made people feel like he was not grateful for what Lyndon Johnson had done. But that’s not really what the major issue was, because everything is over economics. When Daddy talked about Vietnam, he didn’t just talk about it from a moral standpoint; he talked about it from an economic standpoint. It was interesting that in Vietnam we were able to design bombs to bomb villages yet our bombs never bombed any of the poppy fields. So he was getting on to an economic issue, a corrupt economic issue. And that’s when people started saying, “Well, hmmm, he’s talking about turf.” In late 1967 he called for a poor people’s campaign, and he talked about redistributing the wealth and resources of this land. That’s what he was killed about: redistributing the wealth and resources. And if anybody could’ve organized the masses to say, “We want this wealth redistributed: he could have. So the powers that be said, “Well, he’s got to be removed.” That’s my understanding of what happened. On his economic ideas, I believe he was saying, “Teach a man to fish, and he’s fed for a lifetime.” We gotta teach people how to provide food, clothing and shelter for themselves. What that means is that the wealth has gotta be redistributed to some degree. It’s absurd, he said, to have so many millionaires in America who’ve got so much and at the same time to have so many poor. So there needs to be some balance – that’s what he was saying. And he had the ability to unify masses of people – not just black people but white people too. He started to bring in whites in 1965, and white ministers started supporting the civil-rights effort. When they started seeing his leadership of the masses – the moral leadership, the spiritual leadership he could provide as a preacher – they said, “This guy is dangerous.”

As the years went on I was introduced to a friend of Dr. King who helped him write his speech “A Time to Break the Silence” in 1967 named Vincent Harding by the marvelous activist and leader Grace Lee Boggs of Detroit. Dr. Harding wrote a book about Dr. King called The Inconvenient Hero. It illuminated the pressure that Dr. King courageously brought to bear on economic injustice, militarism and racism. It is the clearest portrait of who I believe Dr. King really was that I have read to date.

Dr. King is not just a historical deity. A student of his thinking will see his vision of a universal basic income discussed in a speech at Stanford University 45 years before it became popular in Silicon Valley and Palo Alto to address the disruption of technological change in the digital era.

Dr. King wrote and spoke presciently in his speech called, “The Other America” that was delivered in California, New York and Detroit in the last months of his life about a dual economy that, at that time, was focused on the differences between white Americans and black Americans in the cities that had exploded. As he gave that speech he was holding meetings with Hispanics, whites and Native Americans to plan a Poor People’s March that Reverend William Barber and Liz Theoharis have reinvigorated now 50 years later.

Looking today at the work of Dr. Peter Temin in his book The Vanishing Middle Class, we see that the toxicity of racism continues and furthermore we see that the divide has deepened as more and more Americans descend into stagnation and poverty.

Dr. King’s agenda is as urgent as ever and it should not be masked by a deified hero image that encourages us to avert our gaze from the challenge in front of us. As Michael Eric Dyson wrote 10 years ago in his book entitled, April 4th, 1968: Martin Luther King’s Death and How it Changed America,

Whites want him clawless; blacks want him flawless.

and

He has been idealized into uselessness for the poor he loved, immortalized into a niceness that dilutes the radical politics he endorsed. His justice agenda has been smothered by adulation.

Dyson goes on to quote Andrew Young who asserts:

Martin has become a larger-than-life symbol, almost a deity, rather than the flesh-and-blood man I knew. There is a danger in this. We should not lose our sense of how the civil rights movement happened, because if we do, younger generations, along with ourselves, will lose a sense of how new opportunities were fought for, and won. In blurring, or ignoring, the context of the struggle, the veneration of Martin Luther King becomes devoid of depth and context, and the ability to use his model to renew the struggle for a just and equitable society is lost.

Andrew Young is right to emphasize the depth and context of the struggle that Martin Luther King fought. Economics was at the center of that struggle and to study the visions of tragedy and the blueprints of health (such as the Freedom Budget for All Americans that Dr. King helped create under the leadership of A. Phillip Randolph) helps us as we strive to put it at the center of the struggle today.

Andrew Young was also well grounded in his fear that King’s model might be lost as a guiding light. But in the suffering and tension of tragedy there is often regenerative energy. James H. Cone has written about this masterfully in his superb book The Cross and the Lynching Tree.

Even in the moments just after Dr. King’s death, Robert F. Kennedy shared a vision in Indianapolis. Kennedy quoted Aeschylus:

In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.

It is hard to know if our society can meet these challenges. It also hard to imagine life if we do not.

The resistances are real. Dr. King himself envisioned these tensions in his sermon called “The Drum Major Instinct”. He talked about the attractions of conformity to the structure of power and the ideas that support them. As Michael Eric Dyson says about this sermon:

The point of King’s sermon was to unmask the yearning “to be important,to surpass others … to lead the parade,” calling it the “drum major instinct” after psychoanalyst Alfred Adler, who argued that “this quest for recognition, thisdesire for attention, this desire for distinction is the basicimpulse.” King argued that the that the hunger for recognitionand praise is understandable; it may even be a healthyboost to the ego. Still, the “drum major instinct” oftentempted individuals to snobbish behavior and drovenations to war to prove their dominance.

Cornel West also writes about the resistances to the vision of the real Dr. King, the one that Vincent Harding wrote about. West writes (today in The Guardian):

In this brief celebratory moment of King’s life and death we should be highly suspicious of those who sing his praises yet refuse to pay the cost of embodying King’s strong indictment of the US empire, capitalism and racism in their own lives. We now expect the depressing spectacle every January of King’s “fans” giving us the sanitized versions of his life. We now come to the 50th anniversary of his assassination, and we once again are met with sterilized versions of his legacy. A radical man deeply hated and held in contempt is recast as if he was a universally loved moderate. These neoliberal revisionists thrive on the spectacle of their smartness and the visibility of their mainstream status – yet rarely, if ever, have they said a mumbling word about what would have concerned King, such as US drone strikes, house raids, and torture sites, or raised their voices about escalating inequality, poverty or Wall Street domination under neoliberal administrations – be the president white or black. The police killing of Stephon Clark in Sacramento may stir them but the imperial massacres in Yemen, Libya or Gaza leave them cold. Why? Because so many of King’s “fans” are afraid. Yet one of King’s favorite sayings was “I would rather be dead than afraid.” Why are they afraid? Because they fear for their careers in and acceptance by the neoliberal establishment. Yet King said angrily: “What you’re saying may get you a foundation grant, but it won’t get you into the Kingdom of Truth.”

Dr. King, late in his life increasingly walked alone. He walked alone amidst the crowd despite the attacks from the media and many of his fellow civil rights leaders. He was an inconvenient hero and his agenda was fiercely challenging to the structure of society.

Today one senses that many people are despondent and question the legitimacy of governance and economic institutions in our advanced economies. Today there is not just a fear of the elites but also a fear of disintegration of society if the body politics abides the design of the elites. The challenge now appears to me to envision how we can put back together society, broaden prosperity and opportunity and reestablish legitimacy and trust. In recent weeks there are signs that suggest that we might do better. Young people are rising. Not opportunistically operating to please the powerful or conform to a stale notion of hierarchical authority. They know they need new maps and better maps.

I am often asked what is new economic thinking? I say that new economic thinking is something different than the conventional wisdom that failed yesterday. It is not novelty. It is an economics that is rigorous, evidence-based when it can be, and focused on the real problems of society today. We are now in an unsustainable social dynamic. We need to reimagine what is good for our country. The old model is failing in many respects. There are new structural dimensions that were not present during Martin Luther King Jr.’s lifetime. But the vision that he provided us of the evils and of the possibilities are a very good compass to meet the challenges of tomorrow. And the political will to rise to the occasion will have to accompany the augmented vision of Dr. King. I sense that there is a new vitality of activism on the horizon.

Interestingly an example includes the videos of the granddaughter of Martin Luther King Jr, Yolanda Renee King, age 9, and of another young woman named Naomi Wadler, age 11, as they gave speeches at the March for our Lives rally to support gun control. They and the young people around this world who are increasingly vocal and active inspire me to believe that they just might answer the call of Dr. King’s agenda and answer the call to action of June Jordan, the poet and activist who once wrote in a poem:

And who will join this standing up

and the ones who stood without sweet company

will sing and sing

back into the mountains and

if necessary

even under the seawe are the ones we have been waiting for

Below is a series of links to videos, speeches and books to help anyone who wants to delve deeply into the vision and life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr and what it perhaps portends for our future. You can also see other essays and videos published and shared by INET on MLK’s Economic Legacy and the Economics of Race.

Read

- A. Phillip Randolph Institute, A “Freedom Budget” For All Americans (1966)

- Taylor Branch’s The King Years trilogy (2006)

- Sam Bowles Remembering MLK (2010)

- James H. Cone, Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or a Nightmare (1991)

- James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (2011)

- Michael Eric Dyson, April 4, 1968: Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Death and How It Changed America (2008)

- William Greider (for Rolling Stone), “Martin Luther King III: The Rolling Stone Interview” (1988)

- Vincent Harding, Martin Luther King: The Inconvenient Hero (2008)

- Harding was a friend of King and drafted his famous 1967 Riverside Church speech, in which King publicly denounced the American war in Vietnam—Ed.

- Martin Luther King, Jr., A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches (2003)

- Martin Luther King, Jr. (ed. Cornel West), The Radical King (2015)

- Cornel West, “Martin Luther King Jr was a radical. We must not sterilize his legacy,” The Guardian (2018)

- Martin Luther King, Jr., The Trumpet of Conscience (2010)

- William F Pepper, Esq, The Plot to Kill King, The Truth Behind the Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. (2016)

Listen

- Martin Luther King, Jr, “The Other America,” narrated by Wanda Sykes (2018)

- Martin Luther King Jr. Massey Lectures

- Seeing White podcast

Watch

- “The Betrayal by the Black Elite” (with Cornel West), TheRealNews (2015)

- “Dr. Cornel West on the Unpopular James Baldwin” (2017)

- Cornel West, “American Democracy” (2018)

- “Ex-Speechwriter, Confidante Dr. Vincent Harding on Dr. Martin Luther King’s Courageous — and Overlooked — Antiwar and Economic Justice Activism,” DemocracyNow (2008)

- “The Greatest Speech Ever - Robert F Kennedy Announcing The Death Of Martin Luther King” (1968)

- “Harry Styles, Katy Perry, And More Celebs Come Together In New MLK Video Tribute” (2018)

- James Brown at Boston Garden April 4 1968: Concert after the killing of MLK Jr. (1968)

- They wanted to cancel the concert and James Brown called the Mayor Kevin White and said “Do not cancel it. Put it on PBS and keep people off the streets”—RJ

- James H. Cone talking with Bill Moyers on The Cross and the Lynching Tree (2014)

- King in the Wilderness (dir. Peter Kunhardt) (2018)

- Martin Luther King, Jr., “Mountaintop Speech” (1968)

- Martin Luther King, Jr. and Harry Belanfonte on “The Tonight Show” (1968)

- “MLK Jr.’s granddaughter: No guns in this world” (2018)

- “MLK Jr’s granddaughter: I have a dream … enough is enough” (2018)

- “Vincent Harding – The Inconvenient Hero, Martin Luther King,” Ikeda Center (2010)