America’s healthcare system is collapsing — but not evenly. It’s fracturing into separate realities.

Call it MADA: Making America Divided Again.

Once held together by a strong federal backbone, public health in the U.S. is now tearing into a patchwork of wildly unequal systems. From vaccine access to basic care, your ZIP code may determine whether you live. Or die.

As federal agencies weaken under political interference and anti-science leadership, states are left to pick up the pieces.

Phillip Alvelda, a former DARPA program manager in the office that helped pioneer synthetic biology and mRNA vaccine technology, argues that some states, especially science-driven “blue states,” have the tools, the talent, and the financial wherewithal to build their own public health infrastructure.

This includes real-time disease surveillance, universal care, and even the development of next-generation vaccines. Whether they seize this opportunity remains to be seen. Meanwhile, other states are moving in the opposite direction — dismantling protections, slashing funding, and aligning with private interests that put profit ahead of public health.

In a conversation with the Institute for New Economic Thinking, Alvelda explains how this crisis presents a rare chance: to rebuild a system that is leaner, smarter, and truly centered on care rather than profit.

Lynn Parramore: Let’s start with the current state of America’s public health. What concerns you most right now?

Phillip Alvelda: There are so many assaults on different fronts. But perhaps the most significant change is the claw back of Medicare and Medicaid support. An estimated 17 million people could lose their health insurance.

But that number underrepresents the impact. For many, losing health insurance means losing access to care altogether. These are vulnerable populations with no other safety nets. And now there’s talk in Congress about requiring proof of work to receive coverage. It’s a draconian move that amounts to a money grab. People will die without care.

We’re also seeing changes in leadership at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which are now pushing anti-science, anti-vaccine policies. They’ve fired many experienced third-party advisors and replaced them with people who have little experience and long-standing anti-vax positions. The new leadership has already made access to COVID vaccines more difficult and expensive. They’ve removed distribution requirements and failed to approve important drugs like Novavax.

We’re seeing a coordinated campaign against one of the most effective public health interventions in human history — vaccination. The consequences are deadly.

LP: Given the collapse of federal public health infrastructure, do you think states might effectively step in to build the kind of real-time health monitoring systems we need for managing ongoing and future health crises?

PA: I often refer to this as the surveillance piece of public health. Effective surveillance requires infrastructure, clear policy, and enforcement. It’s not that expensive, but it is absolutely essential.

Unfortunately, we’re now up against an anti-science movement that actively resists data collection because it might contradict their political agendas. The CDC has cut funding, stopped maintaining key websites, and allowed once-impressive national surveillance systems to collapse.

But yes, states can and should pick up the slack. Wastewater testing, hospital reporting — these are affordable, manageable systems. States like California already have the infrastructure and capacity to implement them.

This isn’t just about COVID anymore; we’re also facing rising threats like bird flu and measles due to weakened vaccination efforts. To respond effectively, states need to maintain their own reporting requirements. And if only the science-oriented “blue states” have the political will, then perhaps it’s time to form a coalition — a networked public health system to safeguard against future crises.

Our once-envied institutions, like the CDC and HHS, have lost independence, but this is an opportunity to build new agencies, funded and governed by the states. Perhaps a California CDC, a New York CDC, or a regional blue-state CDC, and so on.

LP: That makes sense. States like California and New York already have strong public health departments.

PA: Exactly. These states live and die by public health. The economic impact of long COVID alone is already visible.

California, New York, Oregon, Washington, Massachusetts — these states absolutely have the capacity to lead. And they can also stand up to the insurance industry. A state can decide what it wants to pay for and how.

This is urgent. We need to act now — recruit the right people, who, by the way, are newly unemployed due to federal cuts.

LP: So the talent is there—it’s just a matter of policy and funding?

PA: Yes. We need state-level policy leaders willing to back it and budget for it. Surveillance is just one area. We also need broader bio-surveillance.

LP: Are you concerned about the risks posed by biological research or virus development efforts in other countries?

PA: Absolutely. The technology needed to make dangerous viruses is not very advanced – all you need is basic lab equipment and a few knowledgeable people. The global impact of COVID has surpassed that of nuclear weapons. Yet we spend far more on preventing nuclear accidents than on preventing biological disasters.

LP: Viruses and diseases don’t respect state lines. If we end up with essentially separate public health systems—one for red states and another for blue—with different rules for regulation, surveillance, and response, what does that mean for the country as a whole?

PA: That’s exactly the danger of the “leave it to the states” approach. We’ve already seen the consequences — fatality rates as much as seven times higher in areas with low vaccination rates and underfunded health systems.

We need state-level public health systems that are universal, accessible, and focused on prevention. Wealthier states must lead the way, because when one part of the country is vulnerable, we’re all at risk.

LP: Could blue states take the lead in developing next-generation vaccines—like the nasal mucosal vaccines widely held to be especially effective at stopping COVID infections?

PA: They absolutely could, and they should. States like California, with world-class research institutions and a thriving biotech sector, are uniquely positioned to lead the next wave of vaccine innovation. Nasal vaccines, in particular, could be a game-changer.

If the federal government won’t lead, states have to. That means building and maintaining the entire vaccine development pipeline, from education and research to clinical trials and manufacturing.

Right now, that pipeline is under threat. Funding for advanced training programs has been slashed by nearly 50%, and we’re actively discouraging the international talent that has long powered American science.

California, for example, should invest directly in universities like UC Berkeley and Stanford, and support in-state clinical trials. We may not be able to preserve the full national infrastructure, but we can build strong, self-sustaining regional capacity. The stakes are too high to wait.

LP: So, potentially, a resident of California could get access to a vaccine that isn’t even available in another state?

PA: It’s already happening. Some states have stopped stocking key vaccines entirely. We’ve effectively fractured into multiple healthcare systems, where your access to lifesaving medicine depends on where you live. It’s a dangerous precedent, and it’s accelerating.

Poor healthcare in under-resourced states isn’t new, but it’s more visible now, thanks to broader media coverage and national crises like COVID. The Trump administration accelerated the dismantling of the safety net. Rural hospitals are shutting down. Public health infrastructure is collapsing. More and more, the system is designed to serve the wealthy—while abandoning workers and the vulnerable.

We’re already seeing the cost: the life expectancy gap between wealthy white Americans and poor Black Americans is now about seven years. It’s even worse for Native Americans.

That’s not just a health disparity. It’s a national failure.

LP: Let’s talk about AI. What role could it play in addressing the failures of our healthcare system?

PA: There’s huge potential, though not necessarily in the ways people expect. While many worry about AI replacing jobs, it’s already outperforming doctors in one of the most critical areas: diagnostics.

General AI models like Claude, ChatGPT, and Gemini are now achieving diagnostic accuracy rates above 90%. For comparison, the average physician gets it right only about 20% of the time, and even top-performing doctors cap out around 40%. That’s a staggering gap — and a massive opportunity to expand access, improve outcomes, and reduce medical errors, especially in underserved communities.

Consider the case of long COVID. Most clinicians are out of date on it, haven’t read the latest papers, and so on. Patient-led treatment groups are doing a better job directing clinical trials. AI models, with access to the latest research, are proving more helpful than clinicians in treating long COVID.

LP: Could AI also help with public health surveillance?

PA: Yes. It can help analyze trends, predict outbreaks, and guide policy decisions in response to real-time surveillance data. For example, if the surveillance system detects rising viral loads, AI can recommend specific mitigation steps — like indoor air quality mandates for schools.

LP: Paint a picture of your vision for a better healthcare future. What does it look like?

PA: First, we have to confront the reality: our healthcare system is driven by profit, not care. It’s bloated with administrators, insurance middlemen, and pharmacy benefit managers—all extracting value without delivering any actual healthcare.

Health insurance isn’t healthcare—it’s a financial product designed to limit access and deny claims. The ratio of administrators to care providers is absurd. We’re spending more and getting less.

If the federal system continues to break down, we have a rare opportunity to build something better from the ground up. Strip away the bureaucracy. Fund doctors and nurses directly. Deliver real care to everyone — not just coverage, but actual services that improve lives.

We’d save money. We’d save lives. It’s time to build healthcare, not health insurance.

LP: How effective do you think private integrated care models like Kaiser Permanente really are? Do they offer a path toward better healthcare, or do they share some of the same systemic problems as the broader industry?

PA: Kaiser is probably one of the more efficient ones, but don’t mistake their giant buildings for good governance.

They suffer from the same disease: they claim, “We’re only generating 3% profit,” but they grew 20% last year. How did they grow? Not in doctors and nurses. They grew in administrators and overhead. They’re becoming larger and more impactful for shareholders, but less impactful for actual care.

Kaiser is very good at managing and minimizing the cost of care — with a huge apparatus generating administrative overhead and revenue. So yes, they fall into the same category as others.

Another example would be pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). PBMs were originally designed to stand between consumers and pharmaceutical companies, using collective bargaining and economies of scale to negotiate better prices and pass savings on to the consumer. But once pharma companies realized what was happening, they started acquiring PBMs. And then PBMs were turned against the consumer, to extract more money on behalf of pharma.

PBMs became one of the most rapacious tools of the last few decades. Several states, like Oregon, have now cracked down on them for that reason. But we still have rapacious pharmaceutical companies charging hundreds of dollars for things like insulin that cost just a few dollars to make.

LP: States like Oregon are also restricting private equity from getting involved in medical practices. Do you see this kind of state-level action as a promising step?

PA: Absolutely. I’d like to see more states follow suit. The problem with private equity in healthcare is that it leverages financial tactics to extract increasing profits while cutting back on actual services. This isn’t just a few bad actors. It’s a systemic issue that demands broad, meaningful regulation, not just piecemeal bans.

We need clear, enforceable rules that ensure healthcare funds go directly to patient care — not bloated administration, overhead, or systems designed to deny coverage.

LP: Would you support banning private equity altogether from healthcare?

PA: Honestly, yes. That would be my favorite outcome. But I also recognize that private equity can play a role. The real question is: What limits do we place on profitability? And where can these firms contribute by building systems that provide fair market value?

There are responsible examples. Take Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs — it’s an open, transparent company that sells medications at a fair price and exposes the entire value chain. It’s disrupting the big pharma model, and they hate it.

Unplugging healthcare from the profit machine is essential. Many of these companies market themselves as “just making 3% profit,” but that’s after massive reinvestment in technology, acquisitions, and expansion. To go back to Kaiser, they were building new campuses in Oakland during the height of the pandemic, when everything else was shutting down. And they had their most profitable run ever during that period—even as Americans were dying in record numbers.

This system has created a parasite that’s feeding off Americans, and it’s gotten too big to bear.

The federal government is stepping back, but the states can step forward.

LP: Is there anything you wish the media were focusing on right now but aren’t?

PA: Absolutely. They need to expose how the federal government is systematically dismantling the very institutions that hold this nation together. This isn’t just policy. It’s a fundamental attack on our unity.

We call ourselves the United States because together we are stronger. But that bond is fraying fast.

Rights and access to basic services — abortion, LGBTQ+ protections, healthcare, clean air, education — are no longer universal. They depend on your ZIP code. We’re unraveling the very fabric that binds us as a nation.

This feels like the unresolved wounds of the Civil War reopening, with the Confederacy’s ideology rising again: stripping protections from the poor, suppressing wages, denying education and healthcare. The Supreme Court is pushing these battles back to the states, just like before the civil rights movement. That’s precisely why we established federal agencies — to protect those who states historically abandoned.

Now, we’re watching all that progress unwind. The Confederacy is returning.

LP: You could imagine figures like John C. Calhoun smiling at this.

PA: Absolutely. But there is hope. Strong, responsible leadership exists in many blue states. The problem is the Democratic establishment hasn’t yet grasped that this is an existential fight for democracy itself. Clinging to old norms and moral posturing won’t be enough. We need bold, decisive action.

Here’s the bright spot: California is the fourth-largest economy in the world. It has the power to act independently—in healthcare, education, disease control, public policy—even if the federal government collapses.

What we need now are leaders like Newsom, Hochul, and others to seize that moment. To build the future by making states strong, independent actors stepping into the void left behind.

Economic Analysis and Policy Implications

Administrative Cost Burden

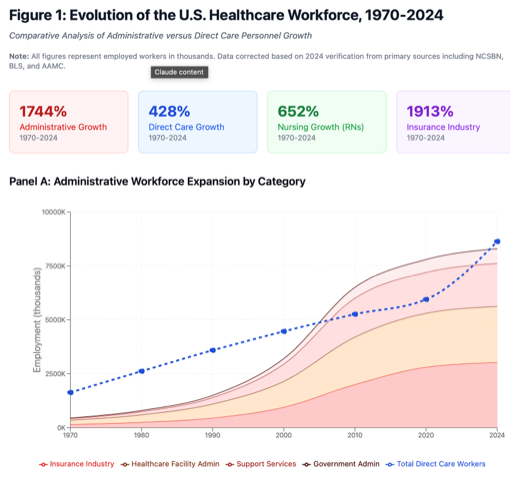

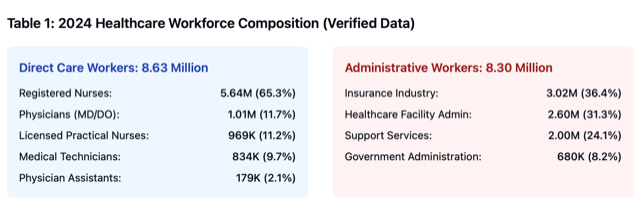

Administrative spending represents 34.2% of total healthcare expenditures, approximately $1.2 trillion annually. This far exceeds administrative costs in other developed healthcare systems (Himmelstein et al., 2020).

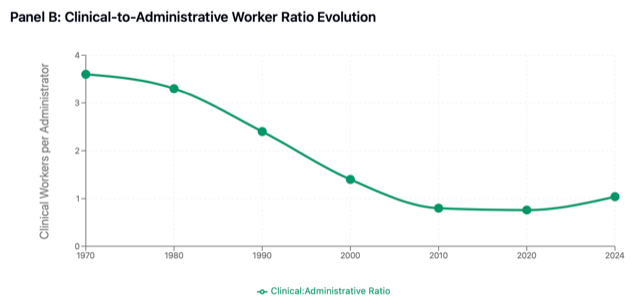

Workforce Structural Shift

The U.S. healthcare system evolved from 3.6 clinical workers per administrator (1970) to near parity by 2024, representing a fundamental restructuring of healthcare labor allocation.

Nursing Workforce Expansion

Registered nurse employment reached 5.64 million in 2024, 61% higher than previous projections, now representing 33% of the total healthcare workforce and driving much of the sector’s employment growth.

Insurance Sector Transformation

Health insurance industry employment expanded 1,913% from 1970-2024, becoming the largest single administrative category and employing more workers than physicians and physician assistants combined.

REFERENCES AND DATA SOURCES

Primary Government Sources

• U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024). Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics.

• U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024). Insurance Carriers and Related Activities: NAICS 524.

• Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Health, United States, 2015.

• Health Resources and Services Administration. (2024). State of the Health Workforce Report.

Professional Association Data

• Association of American Medical Colleges. (2024). US. Physician Workforce Data Dashboard.

• National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. (2024). 2023 Statistical Profile of Board Certified PAs.

• National Council of State Boards of Nursing. (2024). The 2024 National Nursing Workforce Survey.

Academic Literature

• Himmelstein, D.U., Campbell, T., & Woolhandler, S. (2020). Health Care Administrative Costs in the United States and Canada, 2017. Annals of Internal Medicine, 172(2), 134-142.

• Woolhandler, S., Campbell, T. & Himmelstein, D.U, (2003), Costs of Health Care Administration in the United states are Canada. New England Journal of Medicine, 349, 768-776.

Industry Reports

• Insurance Business America. (2024). US insurance employment surpasses 3 million.

• Athenahealth. (2024). How a rise in healthcare administrators is shaping care delivery.

Data Notes: Historical figures for 1970-1990 estimated using CDC Health Statistics, Census occupational data, and professional association reports. Post-1990 data from BLS Occupational Employment Statistics. 2024 nursing data represents active licenses (NCSBN); other professions represent employed workers (BLS).

Methodology: Administrative workforce categories defined as non-clinical positions involved in healthcare financing, regulation, billing, claims processing, and facility management. Direct care workers defined as licensed professionals providing direct patient care services.