Storm argues the AI data-centre investment boom is creating a bubble that will be socially and financially expensive when it pops.

If there must be madness, something may be said of having it on a heroic scale

Introduction

Three years ago, on November 30, 2022, ChatGPT was released to the public. This Large Language Model (LLM) was a total novelty, an AI tool that appeared able to do things that no one believed to be possible. Within five days of launch, over one million users had signed up to chat with the AI bot – a growth rate 30 times faster than Instagram’s and 6 times faster than TikTok’s at their start. It became the fastest-growing consumer product in history, recording more than 800 million weekly users in October 2025. OpenAI, the start-up that developed ChatGPT and that began as a non-profit in 2015, became a household-name almost overnight, and is now valued at $500 billion or even $1 trillion (for an initial public offering). Surfing the LLM wave, Nvidia, the producer of around 94% of the GPUs needed by the AI industry, hit, as the first public corporation ever, a market capitalization of $5 trillion on October 29, 2025, up from just $0.4 trillion in 2022. Nvidia currently has a weight of around 8.5% in the S&P500 Index, while the so-called ‘Magnificent 7’ (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla) have a combined weight in the S&P500 of circa 37%.

The data-centre investments by a concentrated set of hyper-scalers in the American AI industry constitute the main source of growth in an otherwise sclerotic U.S. economy. The U.S. is betting the economy on reaching Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), by building ever bigger computing infrastructure to run and test-time their LLMs, using more GPUs, more power, more cooling water and more data than ever before.

But three years after ChatGPT’s launch, fears are growing in many quarters that the bet on scaling LLMs to reach AGI is going wrong. The AI boom, many whisper, may be a bubble. The Trump administration and the AI industry are showing signs of nervousness. At a recent Wall Street Journal tech conference, OpenAI Chief Financial Officer Sarah Friar suggested that a government loan guarantee might be necessary to fund the enormous investments needed to keep the company at the cutting edge. Her coded message was that OpenAI has become TBTF. The message was understood. President Trump’s AI and crypto czar, David Sacks said (in response) that a reversal in AI-related investments would risk a recession. “We can’t afford to go backwards,” he added, indication support for Friar’s demand. (He later clarified that he remains opposed to any bailouts for individual companies in the AI sector.)

History Rhymes, Or Is This Time Different?

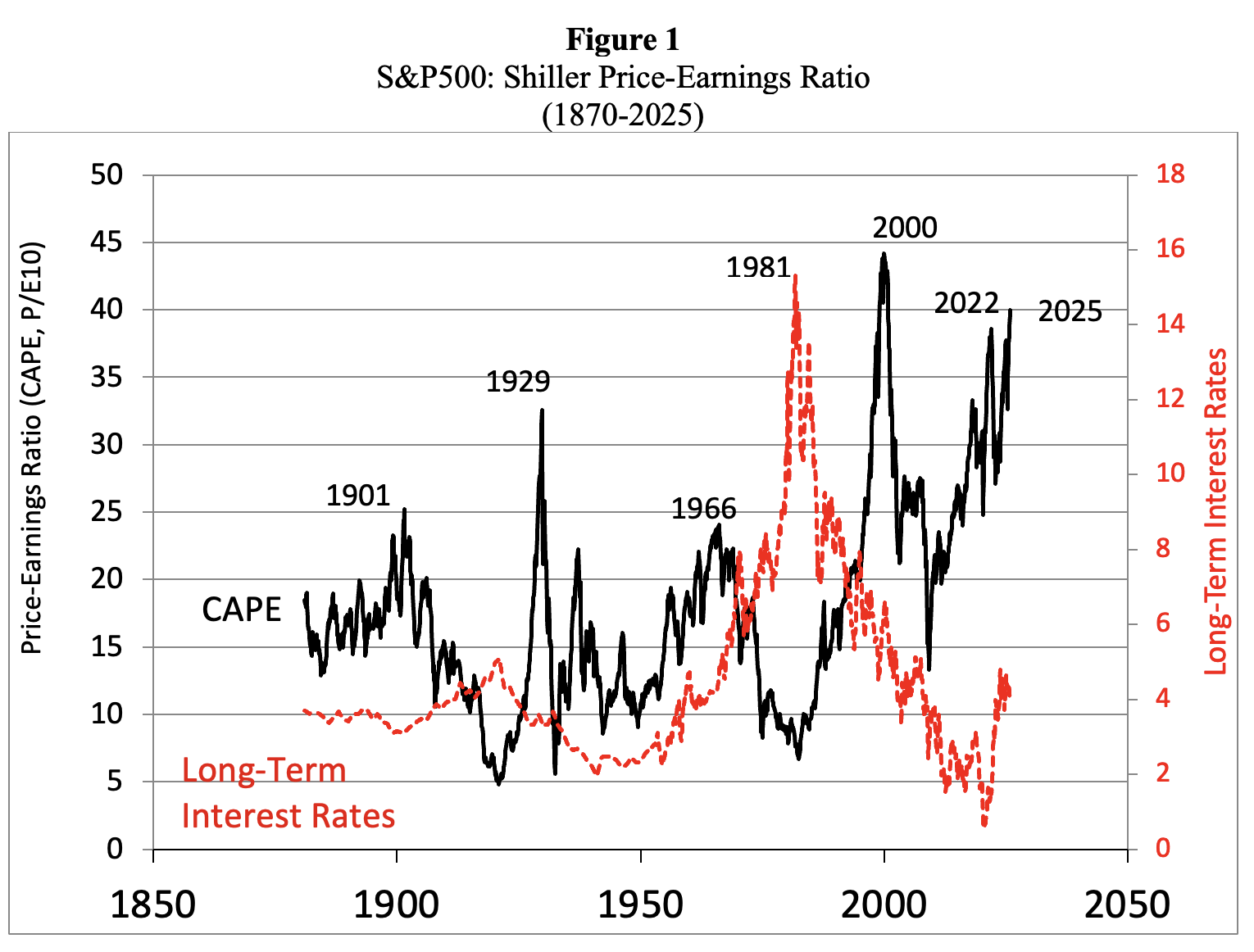

The U.S. stock market is definitely firmly in bubble territory. Figure 1 presents data on the S&P 500’s Shiller P/E Ratio, calculated as average inflation-adjusted earnings from the previous 10 years. Historically, a Shiller P/E Ratio above 30 has been a harbinger of speculative excess, followed by a bear market. In December 2023, the Shiller index rose to 30.45 and has remained above 30 ever since; in November 2025, the Shiller P/E ratio rose above 40.

Since 1871, this is only the sixth instance in which the CAPE Ratio exceeded 30. The first time it happened was during August-September 1929 and we all know what came next: the Dow Jones Industrial Average lost 89% of its value. The second time it happened occurred almost seven decades later: during the end-of-the-millennium dotcom bubble, when the Shiller P/E ratio recorded an all-time high of 44.19 in December 1999. Following the bursting of the dot-com bubble, the S&P 500 lost 49% of its peak value.

The next three peaks above 30 in the Shiller P/E Ratio occurred very recently: during September 2017-November 2018; December 2019-February 2020; and August 2020-May 2022. Following these surges, the S&P 500 eventually dropped by anywhere between 20% and 33%. We are currently living in the sixth such period of speculative excess.

Source: Robert Shiller (2025), https://shillerdata.com/ (accessed on 15/11/2025)

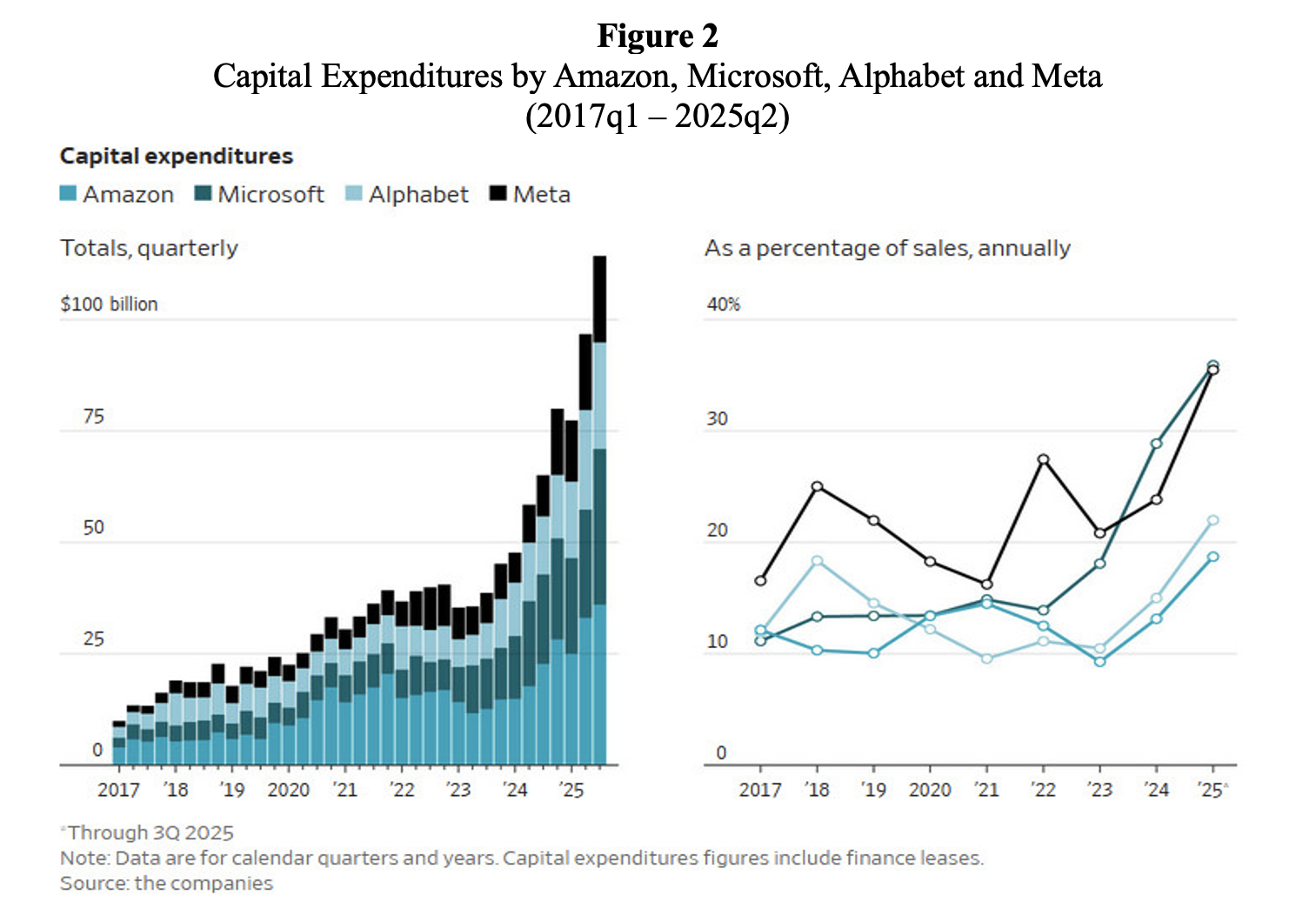

However, the AI party is still in full swing. AI firms are racing to build out data centre infrastructure for what they believe is virtually limitless demand for AI services. Capital expenditures on data-centre infrastructure by Amazon, Alphabet, Meta and Microsoft are steeply rising (also as a percentage of sales) (Figure 2).

JP Morgan Chase & Co projects that 122GW of data centre capacity will be built from 2026-2030 to satisfy the (arguably) astronomical demand for ‘compute’ (Wigglesworth 2025a). The additional 122GW of data centre capacity is estimated to cost between $5-7 trillion. For 2026, the projected data centre funding needs will be around $700 billion, which, according to the report, could probably be entirely financed by hyper-scaler cash flows and by High-Grade bond markets. “However, 2030 funding needs are in excess of $1.4 trillion, which will surpass current market capabilities, necessitating the search for alternative funding sources.”

Source: Christopher Mims (2025), ‘When AI Hype Meets AI Reality: A Reckoning in 6 Charts.’ Wall Street Journal, November 14.

Crucially, most of the mega-financing deals are remarkably circular. To give you a flavour: Nvidia invests in OpenAI and OpenAI is looking to buy millions of Nvidia’s specialized chips. OpenAI buys computing power from Oracle which buys Nvidia’s GPUs. Nvidia owns about 5% of CoreWeave and sells chips to CoreWeave. CoreWeave’s biggest customer is Microsoft, which is an investor in OpenAI, shares revenue with OpenAI, buys chips from Nvidia and has partnerships with AMD. AMD, a rival to Nvidia, was so eager to land OpenAI as a customer that it issued warrants for OpenAI to buy 10% of AMD at a penny a share. OpenAI is a CoreWeave customer and also a shareholder. Nvidia has invested in xAI and will supply it with processors. And so on and so forth. The deals include revenue sharing across the stack and cross-ownership.

Nothing in these circular deals is transparent. It is not clear where the money needed for these deals is coming from. It is not clear what these opaque circular transactions imply for the valuations of the listed and non-public AI firms involved. It is not clear what all this means for the competition over hardware between chip producers (Nvidia versus AMD) and over AI services AI startups (OpenAI versus Anthropic versus xAI versus Microsoft). Not surprisingly, therefore, these astronomical circular financing deals (referencing billions of U.S. dollars) are raising eyebrows. To many observers, they bring back traumatic memories of the circular financing arrangements of the late 1990s, when vendors and clients reinforced each other’s dotcom stock valuations without generating any real value.

AI Bang or Bubble?

AI industry leaders are now busy doubling down on their message that the AI revolution is NOT A BUBBLE, but real and sustainable. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang stated (in an earnings call on November 19) that there is no AI bubble and exponentially growing AI demand is structural rather than speculative. Huang claims that the AI boom constitutes a Big Bang, a historical revolution, because of three fundamental shifts toward accelerated computing: the move from CPUs to GPUs (which can simultaneously process multiple tasks and solutions), the rise of generative AI, and the emergence of agentic AI systems that supposedly can independently make decisions based on large datasets. Asset-managing firm Blackrock concurs: “AI is not just a technological trend; it represents an infrastructure transformation with growing macroeconomic significance”, adding that “unlike the speculative frenzy of the late 1990s and early 2000s, today’s technology leaders are anchored by fundamental stability.” The optimistic vibes around the transformative power of AI have even infected Nouriel Roubini (2025), the profession’s perennial Dr. Doom and now a senior economic strategist at Hudson Bay Capital, who has somehow become convinced that the tailwinds of the unprecedented AI data-centre investment boom will overwhelm any disruptions coming from Trump’s tariffs and geopolitical strains.

But the various statements by Huang, Blackrock and Roubini are “sound and fury, signifying nothing.” The structural demand for Nvidia’s GPUs originates from the same circle of companies that are betting the business on scaling AI. The AI data centres may not be the “shovels of the AI gold rush”, but rather a black hole in which billions of dollars disappear.

The surge in demand for GPUs and data-centre infrastructure may, in other words, very well be speculative, if it turns out that the AI models are not delivering good value for money to the investors – and cannot live up to the exaggerated expectations of the Lords of the AI Ring. Every reader of Kindleberger and Galbraith knows that this would not be the first time in (economic) history that most people – all in the same bubble – had it fully wrong, all at the same time. The financial crisis of 2008 is just the most recent example of a collective mania that ended in a crash.

The Insufferable Irrationality of the AI Industry

The AI race is mostly based on the irrational fear of missing out (FOMO), in Silicon Valley and on Wall Street – which induces a herd mentality to follow ‘momentum’, a complete disregard for fundamental values in favour of placing an exaggerated importance to the limited availability of a key resource (here: Nvidia’s GPUs and ‘compute’), and overwhelming confirmation bias (the all-too-human inclination to look for information that confirms our own biased outlook). To bring home the point: the use of ChatGPT has been found to decrease idea diversity in brainstorming, as per an article in Nature.

It is deeply ironic that the industry that is supposed to build ‘super-intelligence’, a deeply flawed concept with rather sinister origins (see Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna 2025), is itself deeply irrational. But solid anthropological evidence on the local tribes living in Silicon Valley and working on Wall Street shows that this irrationality is hardwired into the perma-adolescent psyches of the inhabitants, who are wont to talk to each other about the coming AIpocalypse, almost religiously believe in AI prophecies, have deep faith in their algorithms, regard AI as a superior ‘sentient being’ in need of legal representation, enthusiastically engage in techno-eschatology, and, above all, are deeply fond of Hobbits and the LOTR. These very same people are also used to talk about and think in terms of billions of dollars as just ‘stuff’ that funds compute, necessary for scaling in order to reach AGI. “I don’t care if we burn $50 billion a year, we’re building AGI,” Sam Altman said, adding: “We are making AGI, and it is going to be expensive and totally worth it.” The same Sam Altman lost his cool during an interview with podcaster and OpenAI investor Brad Gerstner, when he was asked how it all is supposed to add up, given OpenAI’s miniscule revenue. “If you want to sell your shares, I’ll find you a buyer,” a taken-aback Altman replied curtly. “Enough.”

There are more signs of irrationality in the AI industry. In the first six months of 2025, AI start-ups that have no profits, no sales, no pitch and no product to speak of, have been securing billions of dollars of funding. For example, pre-revenue, pre-product AI company ‘Safe Superintelligence’, founded by Ilya Sutskever, ex-chief scientist at OpenAI, raised $2 billion at a $32 billion valuation in April 2025. Similarly, ‘Thinking Machines Lab’, an AI research and product company launched by OpenAI’s former chief technology officer Mira Murati, raised $2 billion at a valuation of $12 billion from investors such as Nvidia, AMD and Cisco in July 2025. The company has not released a product, has no customers and has even refused to tell investors what they’re even trying to build. “It was the most absurd pitch meeting,” one investor who met with Murati said. “She was like, ‘So we’re doing an AI company with the best AI people, but we can’t answer any questions.”

The best AI people are in charge, or so they tell us. A handful of labs, led by Tolkienesque techies, control the narrative around frontier LLMs. The narrative they tell the public is that they are on a mission to build AGI to benefit all of humanity, but this emerging autonomous super-intelligence is so complex and potentially dangerous, even apocalyptic. Anthropic’s chief scientist Jared Kaplan is only the latest in a long line of AI-experts sounding the alarm; or consider Geoffrey Hinton who predicts, once more, the total breakdown of society once AI gets smarter than people. The overblown claims go like this: “It would become impossible for humans to get paid to do work because the superintelligence could do it better and cheaper. You and I would not have jobs. Nobody would have jobs.” The message is clear: reaching AGI is Very Serious Stuff, and Potentially Dangerous. But rest assured: the AI-developers can safely handle these risks and they have the expertise to decide what counts as ‘safe’. Reaching AGI will also need gigantic data-centres, land, electricity and water (for cooling), but don’t worry: the promised results will be transformative and a benefit for all. AGI will find cures for cancer, discover ways to end hunger, solve the affordability crisis, empower students and workers, and somehow also solve climate change. Just trust us, they tell us. Give us the resources we need to build AGI.

But what they tell their investors is altogether different: we are building technology that can “do essentially what you will pay us for”, including making workers redundant by automating jobs or turning them into gig workers while putting them under corporate surveillance. Emily M. Bender and Alex Hanna (2025) recount, for example, how the National Eating Disorders Association in the U.S. replaced their hotline operators with a chatbot days after the former voted to unionise. AI algorithms also work successfully to help landlords push the highest possible rents on tenants. Likewise, the health insurance industry uses AI automation and predictive technologies to systematically deny patients coverage for necessary medical care. AI also works for the military: defence company Anduril builds autonomous drones, virtual reality headsets, and other AI-powered technologies for the U.S. military. And private equity firms are hiring AI people to go through the companies they own and see how these should be restructured.

This way, the AI industry has convinced the financial sector, the cash-rich platform corporations and wealthy venture capitalists to invest their cash in funding the training and inference of the LLMs and the giga-data-centre infrastructure, that is driving the current AGI boom in the U.S. In a new Working Paper, I argue that this AI data-centre investment boom is a bubble which will pop, probably rather sooner than later. This will prove to be socially costly to the larger U.S. economy, not just because of the inevitable correction, crash and recession, but more fundamentally, in terms of the scarce resources that have been and will be wasted on the hallucinogenic pipe dreams of a few entitled Ayn Randian billionaire tech brothers and sisters, who, quite in character and as was noted already above, have begun to hedge their bets by begging the taxpayer for subsidies and government loan guarantees (Cooper 2025). The AI bubble will eventually pop for the following four reasons.

The Revenue Delusion

There is no world in which the enormous spending in data centre infrastructure (more than $5 trillion in the next five years) is going to pay off; the AI-revenue projections are pie-in-the-sky because of the following:

- The costs of training AI models and the cost of inference are rising. It is particularly painful that compute demand is scaling faster than the efficiency of the tools that generate it. As a result, the (operational) costs of inference continue to rise faster than the revenues of the AI companies. This is shown by the very clever financial detective work done on OpenAI’s quarterly revenue and inference costs by Ed Zitron. In fact, the growth rate for AI’s compute demand (which is driven by the industry’s belief that the bigger the scale of AI computing power, the better will be its output) is more than twice the rate of Moore’s law. As a result, the demand for GPUs by the AI industry is soaring and Nvidia, which has a near-monopoly market share of 94% in GPUs, can charge high prices for the newest chips or high fees for leasing the GPUs to the AI firms.

- AI’s inference costs are rising (not declining), even though the cost per million tokens of LLM inference has declined by around 98% — from $20 per million tokens in late 2022 to around $0.40 per million tokens in August 2025 (Barla 2025). However, the AI industry uses considerably larger training data sets now than one or two years ago, and also consumes more tokens because of test-time computing. Test-time computing is the latest approach to scaling LLMs, which allows for longer context windows and bigger suggestions from the models. As a result, a typical enterprise query in 2021 used fewer than 220 tokens; by 2025, models such as GPT-4 Pro and ChatGPT-5 process around 22,000 tokens in a single exchange based on test-time computing. At the current rate of expansion, tokens per query could rise to between 150,000 and 1,500,000 by 2030, depending on task complexity. In effect, with a rapidly declining cost per token and a much larger increase in token consumption per generated word, AI application inference costs have grown about 10 times over the last two years (see Working Paper). Scaling is very costly, in other words.

- The sad truth is that customers are unlikely to pay (enough) for the rather modest services offered by the LLMs and given the eventual oversupply of LLM services. Only 5% of OpenAI users (circa 4 million users) currently are paying subscribers, paying (a minimum of) $20 per month. 95% of everyday users use the free product and remain unconvinced about the value of AI-powered devices and services. More money from usage comes from the 1.5 million enterprise customers that are using ChatGPT. However, enterprises have the option to use much cheaper Chinese LLMs, such as DeepSeek and Alibaba Cloud, which achieve performance levels comparable to leading American AI models and continue to slash prices. The user cost per 1 million tokens is $0.14 for DeepSeek R1 compared to $7.50 for ChatGPT o1. To illustrate the difference: A news website that uses AI for automated article summaries and processes 500 million tokens per month, would pay $70 for DeepSeek R1 versus $3,750 for ChatGPT o1. The cost difference is considerable and impossible to justify in terms of any superior performance of the OpenAI tool. Price competition will drive down user costs charged by U.S. AI firms, which fatally undermines their business model. OpenAI has just has just declared Code Red, after losing 6% of its users in a week due to Google’s new Gemini-3 model. By any reasonable measure OpenAI has squandered the sizable lead it once had. If investors decide to opt out, it will be impossible to keep the operation afloat and OpenAI’s predicted valuation could drop, perhaps dramatically – as happened with WeWork, the value of which dropped rapidly from its peak of $47 billion to near-bankruptcy. If OpenAI goes down, the stock price of Nvidia will as well drop.

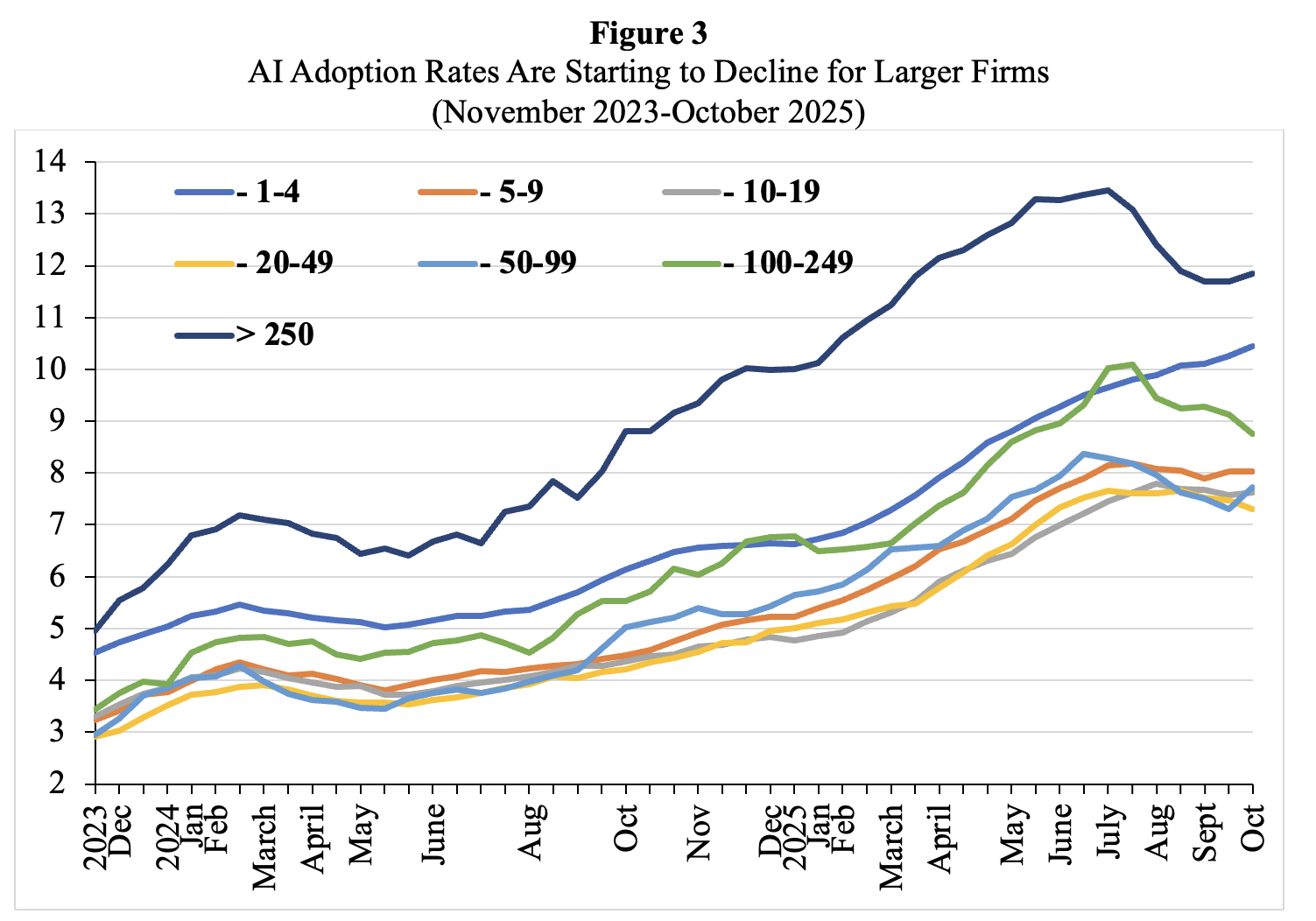

- Finally, user satisfaction with the performance of AI tools is stagnating or even already declining. Enterprise customers are becoming less enthusiastic about their AI tools. Everybody has already heard about the MIT study that showed only 5% of companies were getting a return on generative AI investment. McKinsey (2025) just ran a study, and the results weren’t much different,. McKinsey (2025) finds that two-thirds of companies are just at the piloting stage. Nearly two-thirds of respondents said their organizations have not yet begun scaling AI across the enterprise. And only about one in 18 companies are what the consulting firm calls “high performers” that have deeply integrated AI and see it driving more than 5% of their earnings. The problem is the integration of the AI tools in workflows and organisation. Recent U.S. Census Bureau data by firm size show that AI adoption has been declining among companies with more than 250 employees (Figure 3).

Hence, most AI companies will fail to turn a profit, as prices will fall (because of Chinese competition), while (training and inference) costs go up due to the scaling strategy.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Business Trends and Outlook Survey (BTOS) 2023-2025. Notes: The U.S. Census Bureau conducts a biweekly survey of 1.2 million firms. Businesses are asked whether they have used AI tools such as machine learning, natural language processing, virtual agents or voice recognition to help produce goods or services in the past two weeks. See Torsten Sløk (2025b), https://www.apolloacademy.com/ai-adoption-rate-trending-down-for-large-companies/

The Ticking Time-Bomb of Hyperscale Borrowing

There is no way in which the AI industry can fund its capital expenditures out of revenues from paid subscribers or money from sovereign wealth funds. Hence, AI firms will have to resort to hyperscale borrowing from banks and investment-grade bond markets to fund their capex, laying the foundations for the next debt crisis. This hyperscale borrowing will create a ticking time bomb on the balance sheets of AI firms, because the core capital expenditure is on specialised GPUs and servers, which — because of unrelenting technological progress — risk becoming economically obsolete within two or three years.

Nvidia is not helping in this respect, because it is building new generation GPUs each and every year and GPU prices are likely falling. Nvidia’s latest generation Blackwell GPU’s require entirely new servers, and if you use many of them, an entirely new data centre, because the Blackwell GPUs require much more power and cooling. The rate of economic decay of the AI compute infrastructure, therefore, is high and the payback periods are correspondingly short. “You’re investing in something that is a perishable good,” economist David McWilliams told Fortune, calling AI hardware “digital lettuce” that is “going to go off now.” Data servers, networking equipment and storage devices have a useful lifetime of 3-5 years and a corresponding annual depreciation rate of 20%-30%. These chips are not general-purpose compute engines; they are purpose-built for training and running generative AI models, tuned to the specific architectures and software stacks of a few major suppliers such as Nvidia, Google, and Amazon. These chips are part of purpose-built AI data centres — engineered for extreme power density, advanced cooling, and specialised networking. Together, they form a closed system optimised for scale but hard to repurpose.

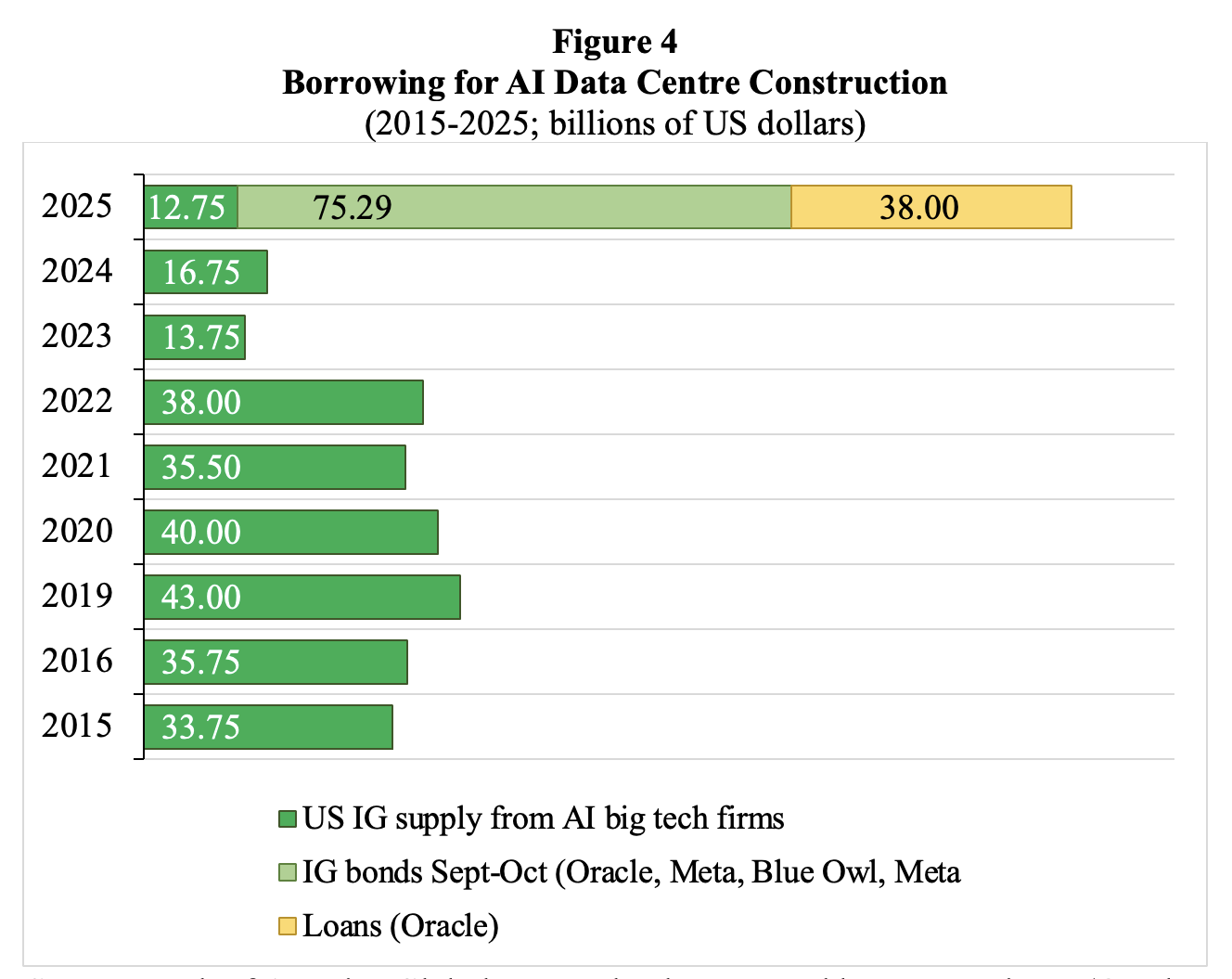

Figure 4 shows borrowing for AI data-centre construction. Investment-grade (IG) borrowing by AI big tech firms during September-October 2025 amounted to $75 billion — compared to $32 billion on average per year during 2015-2024. IG bonds issued by the AI companies make up 14% of the American IG bond market in October 2025. Barclays estimates that cumulative AI-related investment could reach the equivalent of more than 10% of U.S. GDP by 2029, compared to circa 6% in the first six months of 2025.

OpenAI, Anthropic and other startups continue to lose money, and must fund most of the planned investment by selling off pieces of themselves to investors and by resorting to hyperscale borrowing from banks and investment-grade bond markets. Ignoring numerous red flags, particularly operating and financial leverage and the short pay-back periods, virtually every Wall Street player is angling to get a slice of the action, generally via off-balance-sheet Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs), from banks such as JPMorgan Chase and Morgan Stanley to asset managers such as BlackRock and Apollo Global Management. This Wall Street frenzy will in all likelihood lay the foundations for the next debt crisis (Fitch 2025).

Source: Bank of America Global Research; chart created by Lucy Raitano (October 31 2025). Notes: IG = investment grade. The data for Blue Owl and Meta refer to a project-style holding company created by Blue Owl Capital to invest in a large-scale Hyperion data centre joint venture with Meta.

Exponential Growth in an Analogue World

It will be impossible to build the projected data centre infrastructure in the next five years or so (which is the horizon of most AI investors). The lead time necessary to build a hyperscale data centre is currently around 2 years, but expect it to become much longer, say 7 or more years. Why? Upstream suppliers to the growth in data centres — the established industrial companies — have to expand production. These upstream suppliers will run into labour shortages, long waiting times for power grid connections, material bottlenecks and regulatory blowback – and all this will lengthen the lead times necessary to build a hyperscale data centre, as explained in more detail in the Working Paper.

FT Alphaville (2025) further notes that the nature of the AI-related power demand is particularly problematic (Wigglesworth 2025a). It cites a recent Nvidia (2025) report:

“Unlike a traditional data center running thousands of uncorrelated tasks, an AI factory operates as a single, synchronous system. When training a large language model (LLM), thousands of GPUs execute cycles of intense computation, followed by periods of data exchange, in near-perfect unison. This creates a facility-wide power profile characterized by massive and rapid load swings. This volatility challenge has been documented in joint research by NVIDIA, Microsoft, and OpenAI on power stabilization for AI training data centers. The research shows how synchronized GPU workloads can cause grid-scale oscillations. The power draw of a rack can swing from an “idle” state of around 30% to 100% utilization and back again in milliseconds. This forces engineers to oversize components for handling the peak current, not the average, driving up costs and footprint. When aggregated across an entire data hall, these volatile swings — representing hundreds of megawatts ramping up and down in seconds — pose a significant threat to the stability of the utility grid, making grid interconnection a primary bottleneck for AI scaling.”

AI Scaling is Hitting a Wall

The strategic bet of leading AI firms that Generative AI can be achieved by building ever more data centres and using ever more chips is already going bad. This scaling strategy is already exhibiting diminishing returns. It is the wrong strategy, since generic LLMs are not constructed on proper and robust world models, but instead are built to autocomplete, based on sophisticated pattern-matching (Shojaee et al. 2025). LLMs will continue to make errors and hallucinate, especially when used outside their training data. Generic AI products are never going to actually work right and will continue to be untrustworthy.

Three years into the LLM wave, AI-expert Gary Marcus explains very clearly why ChatGPT has not lived up to expectations: “The results are disappointing because the underlying tech is unreliable. And that’s been obvious from the start.” Generic LLMs are hard to control; they still can’t reason reliably and never will; they still don’t work reliably with external tools; they continue to hallucinate; they still can’t match domain specific models, they continue to struggle with alignment between what human beings want and what machines actually do. “The truth is that ChatGPT has never grown up,” Marcus concludes.

Marcus also presents disturbing new research on the performance of frontier LLMs across three benchmarks by CMU professor Niloofar Mireshgalleh. The first benchmark is a math test that could plausibly be answered by large quantities of data. Unsurprisingly, the frontier LLMs perform increasingly well – but, as we saw, at the cost of gigantic volumes of compute. On the second benchmark (which is focused on coding), initial progress in performance is now tailing off, exhibiting diminishing returns. However, as Marcus explains, on the third benchmark, “on a complex task combining theory of mind and privacy that seems harder to game”, the frontier LLMs show slow linear progress – again, at the cost of billions of dollars and huge quantities of electricity and water. In sum, progress in performance on complex tasks is just terribly slow – which is the key factor explaining the disappointment of users of LLMs and the limits to profitable adoption by enterprises.

LLMs are great at generating plausible output – while being much less good at getting their facts straight, while being incapable of reasoning. The hardwired inclination to hallucinate (Metz and Weise 2025) limits the usefulness of AI in high-stakes activities such as healthcare, education and finance. Potential liabilities resulting from the harm done by the decisions of autonomous unsupervised AI tools are simply too large in these high-stake activities — and this will restrict the adoption of and reliance on such AI tools. More generally, we have to think of LLMs, as Bender and Hanna (2025), suggest, as “synthetic text-extruding machines”. “Like an industrial plastic process,” they explain, text databases “are forced through complicated machinery to produce a product that looks like communicative language, but without any intent or thinking mind behind it”. The same is true of other “generative” AI models that spit out images and music. They are all, the authors say, “synthetic media machines” – or giant plagiarism machines. “Both language models and text-to-image models will out-and-out plagiarize their inputs,” the authors write. A large fraction of the output will be AI-slop.

In an ironic twist, the supply of AI-slop will only increase in future, because due to the lack of ‘authentic training data’ , LLMs will increase their input of ‘synthetic’ AI-generated artificial data — an incredible act of self-poisoning. The more AI-slop these models ingest, the greater the likelihood that their outputs will be junk: the “garbage-in, garbage-out” (GIGO) principle does hold. AI systems, which are trained on their own outputs, gradually lose accuracy, diversity, and reliability. This occurs because errors compound across successive model generations, leading to distorted data distributions and irreversible defects in performance. Veteran tech columnist Steven Vaughn-Nichols warns that “we’re going to invest more and more in AI, right up to the point that model collapse hits hard and AI answers are so bad even a brain-dead CEO can’t ignore it.”

Conclusion

Because of these four reasons, AI’s ‘scaling’ strategy will fail and the AI data-centre investment bubble will pop. The unavoidable AI-data-centre crash in the U.S. will be painful to the economy, even if some useful technology and infrastructure will survive and be productive in the longer run. However, given the unrestricted greed of the platform and other Big Tech corporations, this will also mean that AI tools that weaken the labour conditions — in activities including the visual arts, education, health care and the media — will survive. Similarly, generative AI is already entrenched in militaries and intelligence agencies and will, for sure, get used for surveillance and corporate control. All the big promises of the AI industry will fade, but many harmful uses of the technology will stick around.

The immediate economic harm done will look rather insignificant compared to the long-term damage of the AI mania. The continuous oversupply of AI slop, LLM fabricated hallucinations, clickbait fake news and propaganda, deliberate deepfake images and endless machine-made junk, all produced under capitalism’s banner of progress and greed, consuming loads of energy and spouting tonnes of carbon emissions will further undermine and self-poison the trust in and the foundations of America’s economic and social order. The massive direct and indirect costs of generic LLMs will outweigh the rather limited benefits, by far.