Why do market-centric fixes for “unequal exchange” fall short? Sidelining social relations and production power turns colonialism into a pricing problem—and hides the mechanisms that keep uneven development in place.

When Nievas and Piketty published “Unequal exchange and North-South Relations” in early June 2025, many progressive economists were pleased that the colonial foundations of the British Empire were at last being taken seriously in Economics. It was, they thought, long overdue. But the way Nievas and Piketty present, frame and analyze their data on North-South relations perpetuates deeper structural problems with how the discipline deals with colonialism and empire.

There is a vast literature that demonstrates that ‘development’ in the North and ‘underdevelopment’ in the South are closely connected, including through theories of unequal exchange.[1] But Nievas and Piketty empty that concept of its political content. The move is similar to what Piketty did with his book Capital in the 21st Century, where he took the title from Capital but proceeded to treat capital as wealth rather than as a social relation, as in Marx. It is precisely the social relations underpinning the North-South interactions that is missing in the work. As such, insights into the ways in which value transfers globally reflect the uneven development of productive forces gets lost. With social relations stripped away, the framing of the empirical findings end up reproducing the idea in economics that markets, if properly managed and in the absence of colonial coercion, can produce balanced trade. The ways in which unevenness is reproduced through markets are concealed.

In this piece, I critique the theoretical and methodological foundations of Nievas and Piketty’s study that leads them to this frame of analysis. As I will show, those foundations ensure that even when economists try to grapple with imperial subordination and colonial extraction, their frameworks often prevent them from uncovering the underlying industrial, economic and political realities that produce the observed unequal outcomes. I will particularly draw on radical scholarship on uneven development to contrast it with Nievas and Piketty’s understanding of capitalism. But first let’s unpack their headline findings.

North-South relations seen through the current account

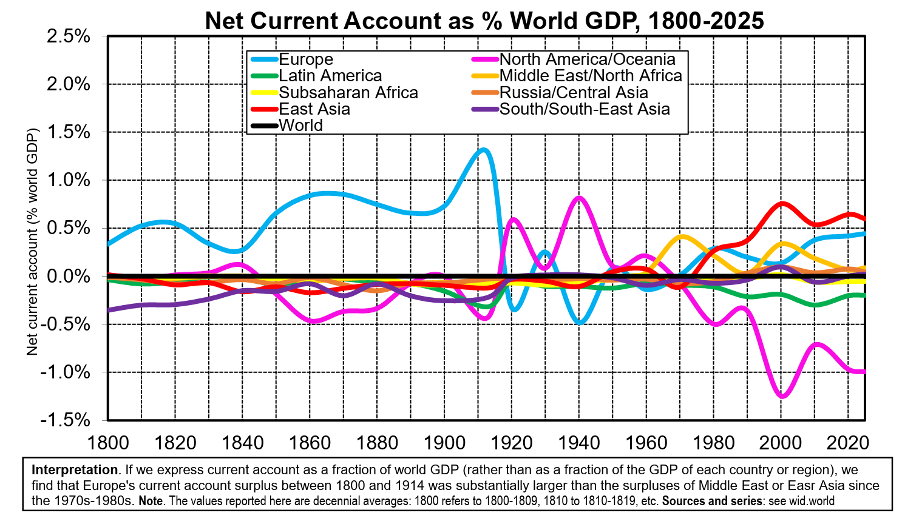

Using a new database developed as a part of their project, Nievas and Piketty find that core European powers had a permanent current account surplus between 1800 and 1914, while the rest of the world had significant deficits (see the current accounts as a percentage of world GDP below). They identify the period between 1800 and 1914, as the ‘first globalization’. However, since the 1970s, in contrast, the main surpluses have come from oil countries in Middle East and North Africa (MENA) as well as from East Asia (driven first by Japan and later China). The only world region in their dataset with a similarly large imbalance as the European core had in the colonial period is North America/Oceania with a structural (US-driven) deficit in the 1990-2025 period. They call this period the ‘second globalization.’ Their whole paper essentially is an analysis of the different elements of the current account for various regions between 1800 and 2025 to explain the shifting nature of North-South relations.

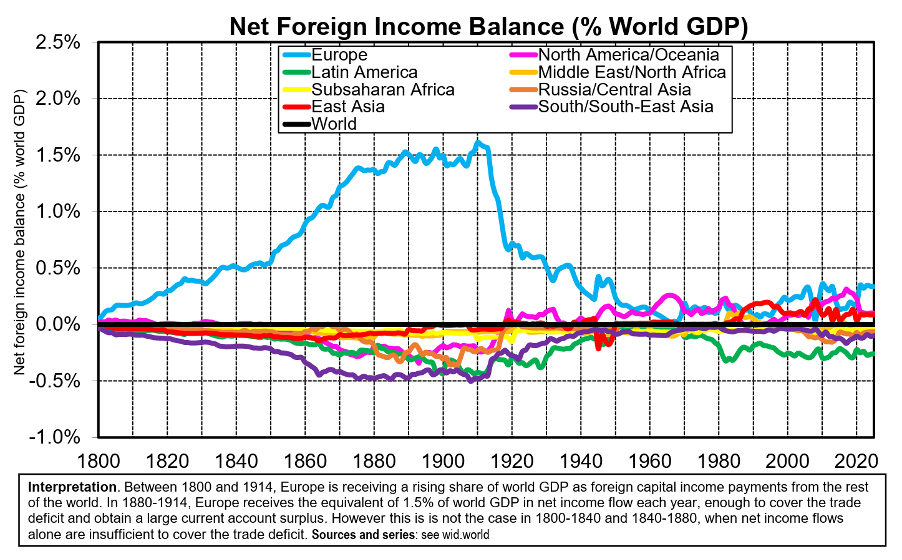

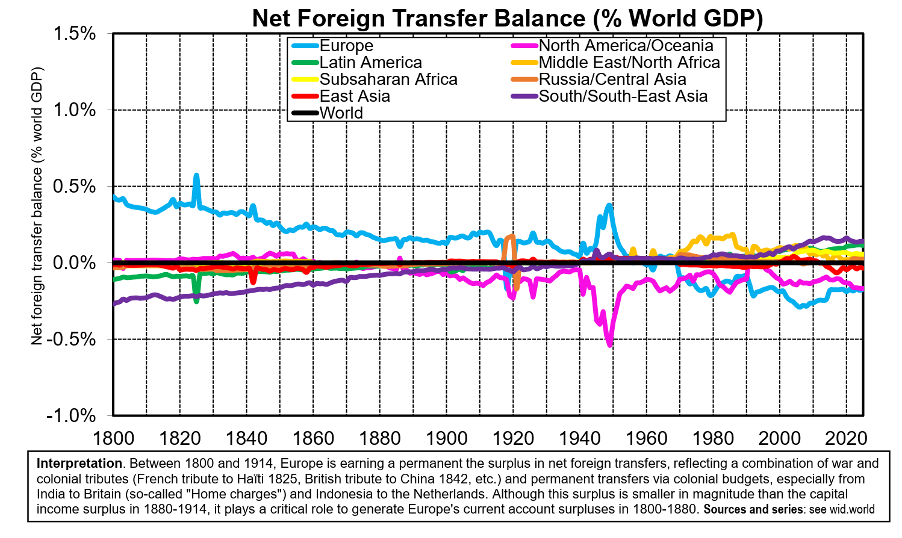

The puzzle they then go on to present is that Europe was in a persistent goods trade deficit between 1800 and 1914. How is this consistent with the observation that Europe had a very high current account surplus in the same period? According to their data, Britain and the other core European countries had surpluses in services, and, more significantly, positive foreign income flows and foreign transfers (see the two graphs below). They find that foreign income inflows – consisting of dividends, interest, royalties and profits from the rest of the world – to the core European countries in the 1880 and 1914 period were so large that no country or region in the world has ever received foreign income inflows approaching that magnitude since. Europe also received significant foreign transfers, consisting of colonial transfers such as one-off tributes and public and private transfers from colonies to the colonizers. Nievas and Piketty then argue that while foreign transfers flowed from South to North in the 1800-1914 period, in recent decades (1970-2025) they flow the opposite way: from North to South. No longer do they consist of colonial transfers but rather of public aid flows, and, most importantly, private remittances sent to countries in the global South from migrants in the global North.

This leads Nievas and Piketty to conclude the following: Under the British Empire, a Britain-led Europe was able to appropriate sufficiently large foreign transfers and income inflows from the rest of the world so that they could transform large trade deficits into large current account surpluses. But in the 1970-2025 period, the US has not been able to do the same. They argue that this can explain some of the “nervousness and aggressivity vis-à-vis the rest of the world observed under the Trump administration in 2025”. They suggest that it seems that Trump would like the kind of financial transfers that Britain received during its imperial period as a compensation for its global leadership, but that the rest of the world is not willing to provide it. This story of shifting current account imbalances is interesting but it tells only part of the story of uneven capitalist development. And in presenting only a partial picture, their paper supports a misleading understanding of capitalism and the balance of forces of our time.

The social relations underpinning uneven development

Nievas and Piketty’s focus on foreign income inflows and transfers is in line with the foundational (implicit) assumption in the Economics discipline that the development of capitalism was a matter of the intensification of existing commercial processes of market exchange, division of labor and technological advancements (a naturalizing view of capitalism). This contrasts with radical understandings of capitalism that take social relations as their starting point. Such understandings recognize that capitalism entailed a structural shift in economic and social organization, from a feudal society to one based on capital employing free labor. This change in social relations started in Britain before the period Nievas and Piketty present data for. Indeed, by the start of their dataset in 1800, Britain is already a capitalist hegemon, and the industrial revolution is well underway. The authors’ suggestions that “foreign transfers play a crucial role in order to start up the process of foreign wealth accumulation” in the early 1800s is therefore historically contested as it dates the ‘start up’ of British capitalist domination much later than what most historians of capitalism would agree to.[2] As such, Nievas and Piketty’s view attributes the accumulated wealth in Britain to income and wealth transfers rather than the global organization of capitalism with Britain at the top of the hierarchy. This is not to say that transfers from the colonies – and before that, from the Transatlantic Slave Trade – were not important for supporting and shaping economic development in Europe. The issue is, rather, that if we take social relations as a starting point, then these transfers can be better understood as reflections of British dominance and not its primary cause.

Radical understandings of uneven development and unequal exchange draw on two key insights which lead to different analyses of capitalism than what Nievas and Piketty put forward. The first is that differences in capital compositions, wages and rates of surplus value across industries and countries generate inequality and value transfers at an international scale, which is has been traditionally called unequal exchange.[3] The second is that if and when value transfers between the North and South exist, they are a consequence of the uneven development of productive forces globally. As such, inequality cannot be understood simply through measuring and reversing income and wealth flows, but, rather, it is the way capital and labor exploitation has been organized globally that must be interrogated. The organization of development at a global scale is important here. Rather than seeing European development as based on technological advancements, cultural traits or hard work, radical scholars argued that development in the global North was – and continues to be – linked to underdevelopment elsewhere.[4]

Nievas and Piketty’s findings support some of the key arguments of these radical frameworks as they demonstrate that colonial transfers matter for European wealth accumulation. However, the difference lies in their setting up a story of capitalist uneven development being primarily about wealth and income transfers rather than about the appropriation of surplus value from labor. As we’ll see, this narrow focus on flows leads to a highly misleading understanding of capitalism and imperialism today, where foreign income (as defined above) mostly flows to East Asia and MENA, and foreign transfers flow from North to South.

It is important to note that Nievas and Piketty’s paper is not an isolated case of studies of history in the Economics discipline neglecting social relations. In the 1970s, the whole sub-discipline of economic history saw a structural move from studies on social relations to studies focusing on neoclassical models aiming to quantify various flows related to the development of capitalism.

The theoretical foundations for understanding capitalism

Nievas and Piketty’s analysis is rooted in an economic framework for understanding trade, growth and global transfers that is based on (late) neoclassical economic theory, although this is only implicit in their paper. They frame their intervention in quite an atheoretical manner, so we have to dig a little deeper to spot the underlying theory via how they frame their assumptions, questions and findings. For example, one of their research questions is centered on whether international economic relations are characterized by “self-correcting market mechanisms”. This assumption of self-correcting imbalances is a foundation of neoclassical trade theory, where exchange rates and domestic prices adjust to balance trade so that we will not see persistent imbalances if we are in a world of perfect markets. This assumption of self-correcting imbalances in foreign trade date back to David Hume’s price-specie-flow mechanism and David Ricardo’s discussion of comparative advantage – and remains a crucial pillar of mainstream economic theory repeated in every economics textbook.[5]

While their observation of a persistent trade deficit alongside enormous wealth accumulation by Britain is posed as an exception to what would be expected in a Ricardian model, their analysis of the post-colonial period is more in line with standard trade theory. They argue that while the net foreign wealth held by European powers at the end of the first globalization was exceptional, since the 1970s foreign wealth accumulation looks much closer to what is usually described in economics textbooks. They find that countries that accumulate foreign wealth are those which have persistent trade surpluses and those with large debts have large trade deficits.

Underpinning their approach is an expectation that trade can in theory balance. This fits with a discipline that generally sees capitalism as a rational system that has the capacity to be even and equal if managed well, in line with a neoclassical framework. This contrasts starkly with more radical traditions mentioned above that see capitalism as inherently uneven and hierarchical. Below we further unpack the consequences of this theoretical and methodological approach in terms of conceptual understanding of colonialism and imperialism, the dynamics of global capital accumulation that underpin current account imbalances, and finally the policy implications of it all.

The separation of economics and politics

Nievas and Piketty’s analysis reveals an understanding of capitalism that separates the economic from the political – a separation that first emerged in the discipline with the marginalist revolution of the late 19th. century. There are several ways in which this separation manifests and shapes the analysis of their paper. The first is that they analyze colonialism separately from capitalism, rather than understanding that colonialism was also subject to capitalist logics. The British state at the time under question was a capitalist state and therefore compelled to support the appropriation of value both domestically and globally. For example, many British corporations sought profits abroad in the 19th century when profits were dipping in Britain, and the colonial state followed to support with legal cover and infrastructure. Colonialism was not outside of or separate from capitalism, or something extra-economic, but rather one of the ways in which the capitalist colonial states secured capital accumulation for their capitals and territory. From such a perspective, setting up a counterfactual where all else is equal except colonial transfers (a part of Nievas and Piketty’s empirical contribution) does not make much sense analytically. What’s more, in separating colonialism from capitalism, Nievas and Piketty also separate colonialism from imperialism. They set up the story of a world economy where imperialism is a thing of the past, rather than the classical imperialist period of the late nineteenth century being only a specific moment in the history of a world capitalist system that is predicated upon imperialist hierarchies and exploitation.

The separation of the economic and the political also shows up is in how Nievas and Piketty treat market mechanisms as implicitly distinct from what the authors consider political forms of power. While we can critique this separation for being inadequate for understanding the world (and it is), it is also worth noting that radical scholars have long noted that the separation of economics and politics is in fact a specifically capitalist way of understanding the world that serves to preserve the current economic order. Economists “emptying capitalism of its social and political content” to study economic or market forces in isolation is a tendency towards apolitical science that dates to the heyday of classical political economy. As such, the popularity of Nievas and Piketty’s framework must also be understood in relation to the political function that it serves, given that it blinds us from seeing how the contemporary capitalist order is itself built on geographically uneven forms of exploitation.

Grasping global capital accumulation at its root

Now let us get to the nitty-gritty of how Nievas and Piketty’s framework shapes our understanding of growth and development. Their primary reliance on current account data and their conceptualization of wealth at only the national scale makes them effectively unable to see how the US today represents imperial power.[6] When analyzing the ‘second globalization’, they do not even mention the new international division of labor that emerged in the 1970s which allowed US corporations to secure profits via outsourcing manufacturing production to the global South, including to East Asia. As such, they are unable to capture the fact that much innovation that supports this production is still highly concentrated in the US, while manufacturing for American companies happens abroad.

When a Foxconn factory exports iPhones to the US from China, India or Vietnam, this shows up as an import to the US even though Apple is an American company. Focusing only on the US trade deficit and sovereign debt sidesteps the ways in which some parts of Chinese production are structured in a way that support the US Empire rather than challenge it. Focusing only on various elements of the current account and seeing the US trade deficit and debt as a source of weakness effectively makes it impossible to see the continued power of US capital in the world today. Rather than focusing on how the world is now, at last, free from colonial transfers, which is a conclusion many will draw from Nievas and Piketty’s work, a more radical reading of the second globalization would rather suggest that the US does not in fact need coercive colonial transfers as the British Empire did, because capitalism is now organized in a way that allows US corporations to keep accumulating at a global scale (mostly) without the support of colonial coercion.

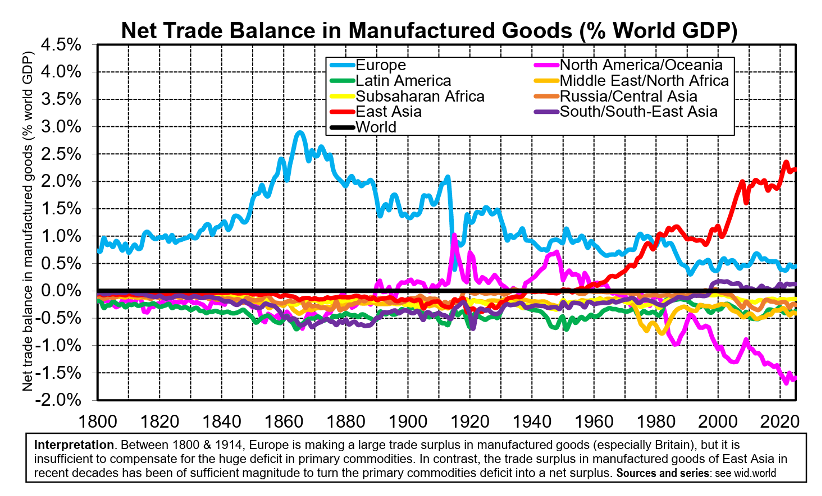

With this alternative understanding of global production in mind, the authors’ argument that East Asia today is the world’s manufacturing powerhouse on par with imperial Europe also falls apart. The authors base this argument on their observation that East Asia’s manufacturing surplus in 1960-2025 is comparable to that of Europe 1860-1914 (see the graph below). This kind of observation – simply based on a comparison of the quantitative expansion of manufacturing exports – does not fully capture the way the political economy of manufacturing production has fundamentally shifted from the first to second wave of globalization.

When focusing only on the trade balance in goods, Nievas and Piketty’s account does not capture that substantial parts of the manufacturing happening in East Asia is controlled by US – or other Western – capital. Instead, Nievas and Piketty’s analysis remains at a surface level given their focus on quantitative flows rather than the qualitative organization of capital and labor. Similarly, their observation that the oil exporting countries of MENA are now in persistent surplus without further analysis or contextualization fails to account for the importance of the US in the global transition to an oil-centered and USD-centered global economy, where countries in the Middle East have played a pivotal role.

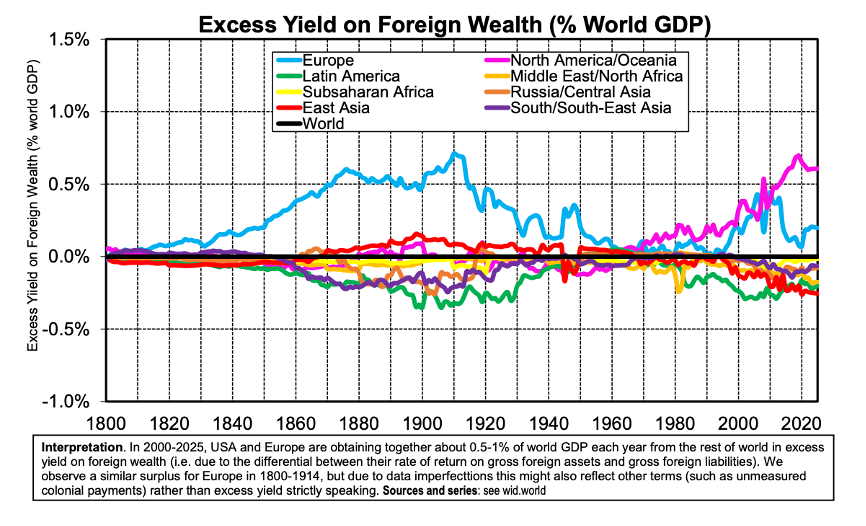

While their analysis of the current account in the second globalization largely supports an idea that the world is somewhat fairer now since the end of colonialism, Nievas and Piketty point to one crucial source of US power of our day, namely its “exorbitant privilege”: They observe that the countries that control the dominant currency and the leading financial institutions of the time can borrow at lower rates and obtain high returns on their foreign investment and thereby earn substantial extra income out of that. Nievas and Piketty call this “excess yield” (because of the differential between their rate of return on gross foreign assets and gross foreign liabilities) and some of the novelty of their dataset is that they can estimate this from 1800-2025 (see graph below). This is illuminating as most discussions and estimates related to exorbitant privilege to date has been limited to the period since the 1970s.[7] Interestingly, their findings show that Europe’s excess yield over the 1800-1914 period is comparable in size to the US excess yield in the 1970-2025 period.

Even while noting this unevenness in the global financial system, there is a lack of reflection in their paper around why the US has the exorbitant privilege that it has. In order to understand that, one would need to explore how the rise of the US as a hegemon was intertwined with the emergence of the USD as world money.[8] Only by connecting these structural factors are we able to see that the ‘privilege’ is a reflection of historical and contemporary power and that the ‘financial’ and ‘productive’ cannot be well understood separately. Without considering this connection, Nievas and Piketty cannot square the fact that the US has both an exorbitant privilege on the one hand as well as a huge debt and trade deficit on the other.

Nonetheless, it is worth noting that Nievas and Piketty are on to something in their search for answers to the rise of Trump in the US. We are in a potentially pivotal period of friction and rivalry in the world, where the contradictions of the system are being very crudely exposed. Nievas and Piketty’s data take us part of the way towards understanding the changing nature of imperialism. But because of their narrow methodology and understanding of capitalism they’re only able to grasp a small part of the picture. And with only a small part of the picture in view, their story risks excluding insights from radical scholarship on how imperialism shapes the world today.

Big inequalities, small tweaks

The policy proposals that come out of Nievas and Piketty’s work flow naturally from their theoretical and methodological framework and findings:

“…unequal comparative development largely stems from unequal exchange, in the sense that a different set of trade rules and institutions could have led to a different pattern of comparative development, and could contribute to do so in the future.”

The authors locate the problem in the sphere of exchange and political power to manage prices, financial transfers, taxes, and currencies. In other words, they are focused on managing the market better, rather than challenging the foundations of the economy itself. For example, one policy proposals is centered on pegging exchange rates closer to purchasing power parities and/or a common currency. Thereby, they maintain the possibility of balanced trade but assume that it is simply the ‘wrong’ exchange rates that have led to imbalances in the world today. Other policy proposals include common borrowing rates to challenge the inequality related to the US exorbitant privilege and a corrective tax on excessive current account surpluses.

More progressive proposals in their paper have to do with challenging the governance of the international financial system itself via reforms of the IMF, including reform of voting rights for countries of the global South. While such changes to international institutions would be welcome by global South countries, there is little reflection in the paper on the political economy of these institutions themselves and the power that underpins reform attempts. The problem is that Nievas and Piketty’s limited theory of power fails to capture the global uneven development of production and how international institutions have evolved to support this development. On the contrary, their theory of power contributes to the masking of the very source of this unevenness.

Their isolation of power into only the realm of market exchange thus leads them to offer only policy mechanisms that can adjust the market in particular directions, such as reforms to credit allocation, price and currency management, and taxes, as well as reforms of the existing international institutions which could further support the promotion of such mechanisms. As such, Nievas and Piketty, while seemingly offering a progressive reading of the role of colonialism in shaping the global economy, end up with a narrow set of policy proposals for managing uneven development that are unlikely to tip the scales substantially in favor of the global South, let alone the working classes of the global South. What’s more, given that those policies will not be adopted unless the power balance in the world changes, focusing on the policies and institutions alone distracts from critically challenging the foundations of the power imbalance themselves. As the radical anti-imperialist economist Samir Amin put it after it became clear that the New International Economic Order could not be implemented given the prevailing power imbalances and capitalist dynamics of the 1970s, those policy proposals “can be ‘speechified’ about without any danger”. When such speechifiable reforms take center stage in political debates, they sweep more radical understandings of imperialism and capitalism out of view.

NOTES

The author is grateful to Thomas Ferguson, Paulo dos Santos, Tom Purcell and two anonymous reviewers for very helpful comments on various versions of this piece.

[1] Some classics include Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications 1972; Andre Gunder Frank, ‘The development of underdevelopment’, Monthly Review 18(4): 17. 1966; Samir Amin, Accumulation on a World Scale: A Critique of the Theory of Underdevelopment, Monthly Review Press 1974. For more contemporary analysis, see for example Ilias Alami, Carolina Alves, Bruno, Bonizzi, Annina Kaltenbrunner, Kai Koddenbrock, Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven and Jeff Powell, ‘International financial subordination: a critical research agenda,’ Review of International Political Economy 30(4): 1360–1386, 2022; Felipe Antunes de Oliveira, Dependency and Crisis in Brazil and Argentina: A Critique of Market and State Utopias. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press 2024; Sam Ashman, Ben Fine and Susan Newman, ‘The Crisis in South Africa: Neoliberalism, Financialization and Uneven and Combined Development,’ Socialist Register (47), 2011; Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven, ‘Beyond the Stereotype: Restating the Relevance of the Dependency Research Programme,’ Development and Change 52(1): 76-112, 2021; and Utsa Patnaik and Prabhat Patnaik, Capital and Imperialism: Theory, History, and the Present. New York: Columbia University Press, 2021.

[2] For some historical analyses of the development of capitalism in Britain, see for example the classic texts Robert Brenner, ‘Agrarian class structure and economic development in pre-industrial Europe’, Past & Present 70: 30–75, 1976; Joseph E. Inikori, Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England: A Study in International Trade and Economic Development, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002; Eric Williams, Capitalism and Slavery, University of North Carolina Press, 1944; Ellen Meiksins Wood, The Origin of Capitalism; New York: Monthly Review Press, 1999. For some contemporary discussions and analyses, see for example David McNally, Blood and Money: War, Slavery, Finance and Empire, New York: Columbia University Press, 2020; Gavin Wright, ‘Slavery and Anglo-American capitalism revisited,’ The Economic History Review 73(2): 353-383, 2020.

[3] For some classic works, see Arghiri Emmanuel, Unequal Exchange: A Study of the Imperialism of Trade. Monthly Review Press, 1972; Samir Amin, 1974; Ruy Mauro Marini, Dialectics of Dependency, Monthly Review Press, 2022 (1973). For contemporary contributions see Jason Hickel, Christian Dorninger, Hanspeter Wieland and Intan Suwandi, ‘Imperialist appropriation in the world economy: Drain from the global South through unequal exchange, 1990–2015’, Global Environmental Change 73, 2022; Tomás N. Rotta, ‘Value capture and value production in the world economy: A Marxian analysis of global value chains, 2000–2014,’ Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 57(2-3), 184-202,2025; Andrea Ricci, ‘Unequal Exchange in the Age of Globalization,’ Review of Radical Political Economics 51(2): 225-245, 2018, and the forthcoming Güney Işıkara, Patrick Mokre, Marx’s Theory of Value at the Frontiers Classical Political Economics, Imperialism and Ecological Breakdown, Routledge, 2026.

[4] We revisit this argument and discuss its implications for the Economics discipline explicitly in our recent book Devika Dutt, Carolina Alves, Surbhi Kesar and Ingrid Harvold Kvangraven, Decolonizing Economics – An Introduction, London: Polity Press, 2025. For a classic critique, see Samir Amin, Eurocentrism, New York: Monthly Review Press (2nd Ed), 2010(1989).

[5] Of course, Marx was an early challenger of this assumption and there’s a strong tradition in heterodox economics of engaging critically with Ricardo and proposing alternative understandings of trade.

[6] The extent and nature of US Empire is vigorously debated today. For some radical understandings, see for example Capasso, M., and A. Kadri. 2023. “The Imperialist Question: A Sociological Approach.” Middle East Critique 32(2): 149–166. Chesnais, F. 2007. “The Economic Foundations of Contemporary Imperialism.” Historical Materialism, 15(3), 121–142; Gindin, Sam and Leo Panitch. 2021. The Making of Global Capitalism: The Political Economy of American Empire. London: Verso; Vasudevan, Ramaa. 2021. “The network of empire and universal capitalism: imperialism and the laws of capitalist competition.” Review of Social Economy 79(1): 76-102.

[7] See for example Pierre‐Olivier Gourinchas and and Hélène Rey, ’From World Banker to World Venture Capitalist: US External Adjustment and the Exorbitant Privilege,’ In G7 Current Account Imbalances: Sustainability and Adjustment, edited by R. H. Clarida, 11–66. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007, or Gastón Nievas and Alice Sodano,. ‘Has the US Exorbitant Privilege Become a Rich World Privilege? Rates of Return and Foreign Assets from a Global Perspective, 1970–2022,’ WIL Working Paper No. 2024/14.

[8] Adam Hanieh, ‘World Money and Oil: Theoretical and Historical Considerations,’ Science & Society: A Journal of Marxist Thought and Analysis, 87(1), 50–75, 2023; Maria N. Ivanova, ‘The Dollar as World Money,’ Science & Society: A Journal of Marxist Thought and Analysis, 77(1), 44–71, 2013; Ramaa Vasudevan, ‘From the Gold Standard to the Floating Dollar Standard: An Appraisal in the Light of Marx’s Theory of Money,’ Review of Radical Political Economics, 41(4), 473–491, 2009.