Why real reform in American politics won’t come from slogans, scandals, or new parties — but from breaking the grip of investor politics and rebuilding power from the ground up.

For decades, the tired story hasn’t changed: big money floods politics, alarms go off, and then comes the usual reassurance — political competition will save us. As long as parties need votes, the system really can’t stay bought, so they say. Politicians, journalists, and scholars have repeated this comforting idea again and again. But while they clung to it, wealth and income gaps soared, and Americans began living in increasingly unequal worlds — even in how long they lived.

Voters see through the charade. They’ve lost trust in the system and grown tired of both parties, fueled by big money. By the end of Obama’s presidency, voter turnout had fallen to its lowest point in decades.

Ever since, politicians on both sides have been scrambling to find new ways to reconnect with a disillusioned electorate. During Trump’s 2016 campaign, the call to “drain the swamp” echoed everywhere — even as many saw Trump himself as the very embodiment of that swamp. By 2025, after billionaires dominated Trump’s second inauguration and Elon Musk, the richest man alive, wielded a chainsaw to cut budgets, more Americans caught on to just how tightly wealth controls politics.

Some Democratic leaders have responded by rallying crowds against “oligarchy,” tapping into that frustration. Meanwhile, billionaire power struggles and scandals kept the media focused on elite conflicts. In New York, where inequality surged faster than in any of the nation’s other nine largest cities from 2019 to 2022, a democratic socialist candidate won the Democratic primary for mayor.

The first step for anyone interested in winning back voter support is recognizing the reality of America’s money-driven system once and for all — and then putting forward real reforms to that system, not empty slogans.

The Real, Unseen Power of Money in Elections

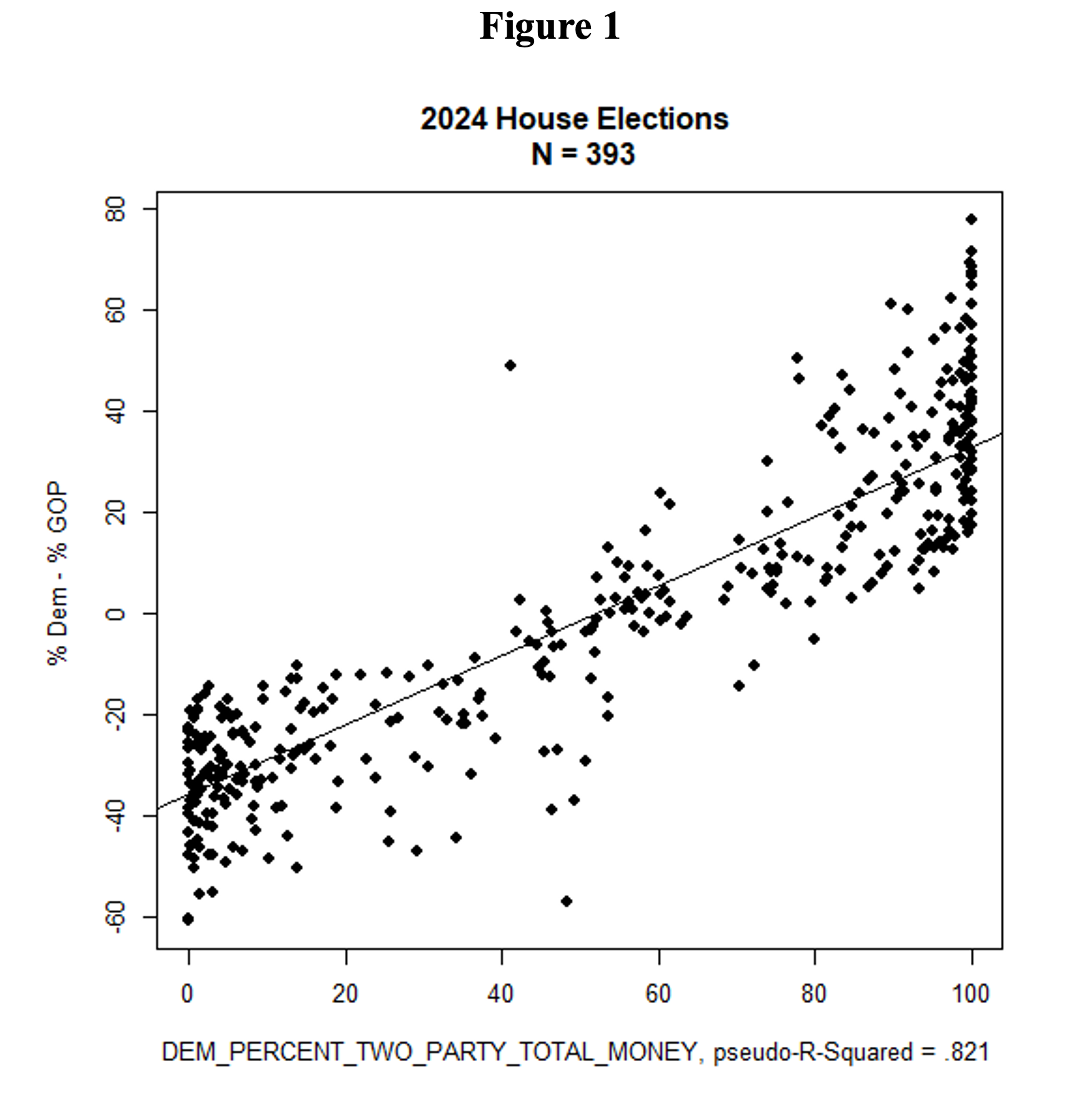

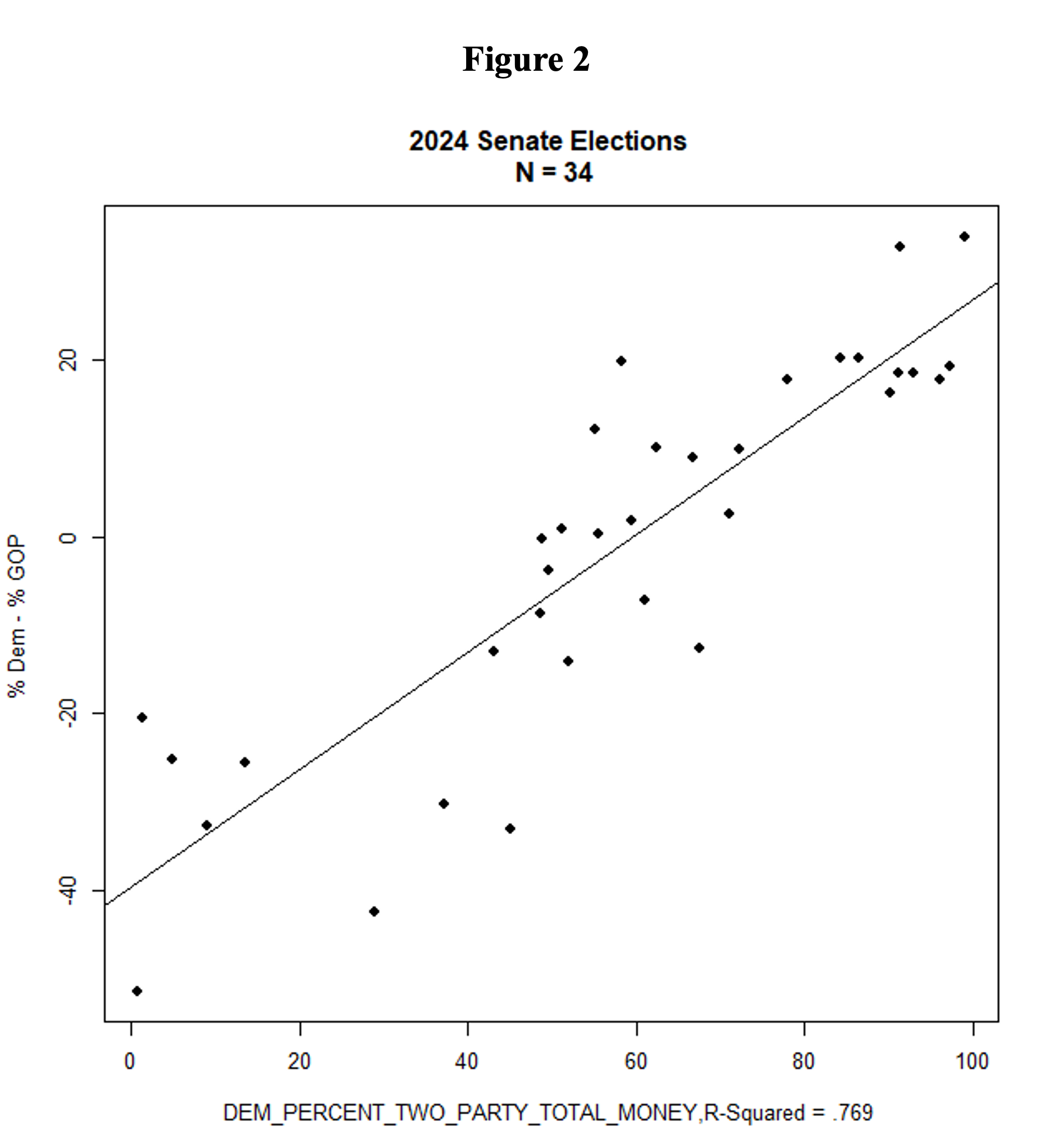

Well before the latest wave of disillusionment, we produced our first statistical demonstration that the outcome of every Congressional election for which the evidence exists – that is, since 1980 – has been strongly driven by political money, meaning that you could predict three quarters or more of the vote from knowing the percentage split in money between the major parties.[1] The rule holds for both the Senate and the House, with the hundreds of cases the latter offers each election making the relationship especially compelling.

The connection between money and votes is so clear and consistent—forming almost a perfect straight line, which we call a “linear model”—that it was hard for us to believe at first. Certainly, nothing in the political science literature ever suggested anything of this sort.

In the early days, we started public presentations with ritual dances of purity lest we convey the impression that money explained everything. We gave that up after the late Francis Bator, the distinguished economist who was Lyndon Johnson’s Deputy National Security Adviser, suggested that it was time to stop apologizing and let facts speak for themselves.

Is Money Really Driving Elections—or Just Following the Polls?

We spent significant time upfront tackling the most common criticism before presenting our full analysis: that the money was not actually shaping outcomes, but mostly followed (usually secret) polls.

Modern methods of “event analysis,” now widely used in finance, allowed us to rule out that money simply follows polls as the general case. We showed that in many races — and likely in nearly every individual contest — big bursts of money, even late in the race, can dramatically change the chances of winning, almost like magic.[2]

Though Democrats sometimes talk about campaign finance reform, neither they nor Republican leaders have seriously pursued it in years.[3] As a result, tracking the increasingly complex and murky flows of money in American elections requires far more time and effort than most media or social scientists are willing to invest. But it can be done.

Our results for the 2024 Congressional races confirm the usual pattern. While a handful of mostly Republican primaries make for minor statistical quirks, there are no surprises.[4] The straight-line relationship is clear as ever.

We’ve placed the technical details in the Appendices and focus here on the key visuals. Figure 1 shows the House results. The vertical axis measures the difference between Republican and Democratic vote percentages—when it’s above zero, Democrats are winning. The upward slope of the line clearly shows that as Democrats receive a larger share of political money, their chances of winning increase.

Figure 2 for the Senate shows a similar pattern, though results for that body, involving less than a tenth of the number of cases the House offers, always look more sparsely ragged.

Money-driven political systems work very differently from the nursery tales of conventional voter-centered approaches. Given the disarray among Democrats and the growing talk of an Elon Musk-led new “American Party,” it’s important to explain the key lessons of the “investment approach” to party competition once again.

The interdependence between issues and constituencies

What truly drives party renewal isn’t slogans or talk — those are cheap and easy, especially online. What matters is how parties handle the hard reality of high campaign costs in real elections, where running a campaign demands huge amounts of money, energy, and time from average voters.[5] And that’s before you factor in the suffocating fog of subsidized misinformation that can choke public debate even in small towns.

The basic rule is simple: In real political systems, only campaign appeals that can be financed can be mounted. As a result, in the absence of networks of organizations readily accessible to ordinary people that enable them to spread costs and take advantage of economies of scale, power passes by default into the hands of major investors and organized interest groups that can bear those costs.

Money-driven political systems do not guarantee that everyday people’s issues get attention. Instead, in key areas like property rights, taxes, labor, and regulations, important debates disappear into a political “Bermuda Triangle” — a zone where real competition vanishes because powerful investor groups all avoid those issues. This does not happen because parties collude — though that happens — it’s because investor-backed parties know pushing costly changes would hurt their funders.

In politics, the biggest obstacles are not natural or accidental — they are deliberate protections set up to defend the interests of the rich and powerful.

Money-dominated systems do manifest a certain kind of competition—but it’s a stylized, limited kind, much like the old American car market before foreign companies arrived. Candidates flood the scene with flashy appeals, video events, fundraisers, and nonstop debates. But for everyday people, it’s mostly theater — a show designed to entertain and reassure donors, not serve voters.

Debates over party and campaign messages mostly rely on biased readings of selectively leaked polls that aren’t fully public and usually lack important controls. In reality, these debates are thinly veiled appeals to donors by party insiders who rarely retire from the stage, no matter how disastrous their advice has been in previous elections. They are competing in rigged contests to see who can create the most convincing voter messages that protect donor interests.[6]

Over time, lawmakers in both parties tend to increase their wealth far beyond that of the voters they represent. When Congress breaks for the summer, party leaders and lawmakers often spend time in places like the Hamptons or on the West Coast, meeting with donors and leaders from both parties. They may appear in social columns, but rarely make major news. Then, in the fall, they return to begin another round of fundraising.

This is why American politics is full of empty promises, loud speeches, and constant scapegoating — where Democrats promise the moon but deliver little more than token reforms.

Real Reform Demands More Than Just a New Party

Starting a new party does not solve the fundamental problem. It’s expensive — in time, energy, and money — and rarely succeeds.[7] The real question is: Who controls the party’s funding? True change only comes when, like during the New Deal, broad popular support promotes policies that help the many — not just the few — and when strong democratic organizations emerge to sustain those policies over time without relying on begging bowls.

Reform efforts are doomed unless they drop the unrealistic belief that money for change grows on trees and acknowledge that parties and policies rely heavily on powerful investor groups. If you think strong antitrust enforcement is key to public welfare and economic growth, it’s self-defeating to expect crucial support from the very trusts you want to regulate—as the Harris campaign learned last year when reaching out to Silicon Valley. That high-profile failure revealed a broader truth: financiers rarely hide their demands anymore, and their influence is widespread.

If you believe higher taxes on the wealthy are needed to reduce soaring public debt without slashing domestic spending, don’t count on most top financiers to put the public’s interest ahead of their own. History shows some can be convinced — sometimes out of enlightened self-interest — but the impetus for real change has to come from elsewhere. Otherwise, reform efforts risk ending up like the Biden administration: after rolling out investment initiatives praised by business groups, not a single major player backed its modest tax reform proposals.

A toxic mix of regulatory loopholes and court rulings currently protects big money’s nearly unlimited right to intervene in elections. Right now, the Supreme Court is reviewing a case that could allow even closer coordination between parties, candidates, and wealthy donors.

But Democrats don’t have to follow the Republicans’ lead. They could reform their party’s rules and practices. (In theory, any new third party could do the same, but we’re not betting on Elon Musk’s proposed party taking that path.) The Democrats, for example, could ban SuperPACs within party primaries, as several U.S. senators have recently suggested.

Democrats could also reform the rules governing national and state parties. Specifically, they could restructure the Democratic National Committee to remove the heavy presence of corporate lobbyists and require easily accessible, full disclosure of all members’ outside affiliations. They could also push for more timely disclosure of campaign financing in party primaries, ensuring voters know who is funding candidates before casting their ballots.

Wealthy Democrats frequently dismiss steps to reduce money’s role in the party by comparing this to unilateral disarmament in the middle of a war. The analogy slips past the crucial point about the interdependence of money and campaign appeals.

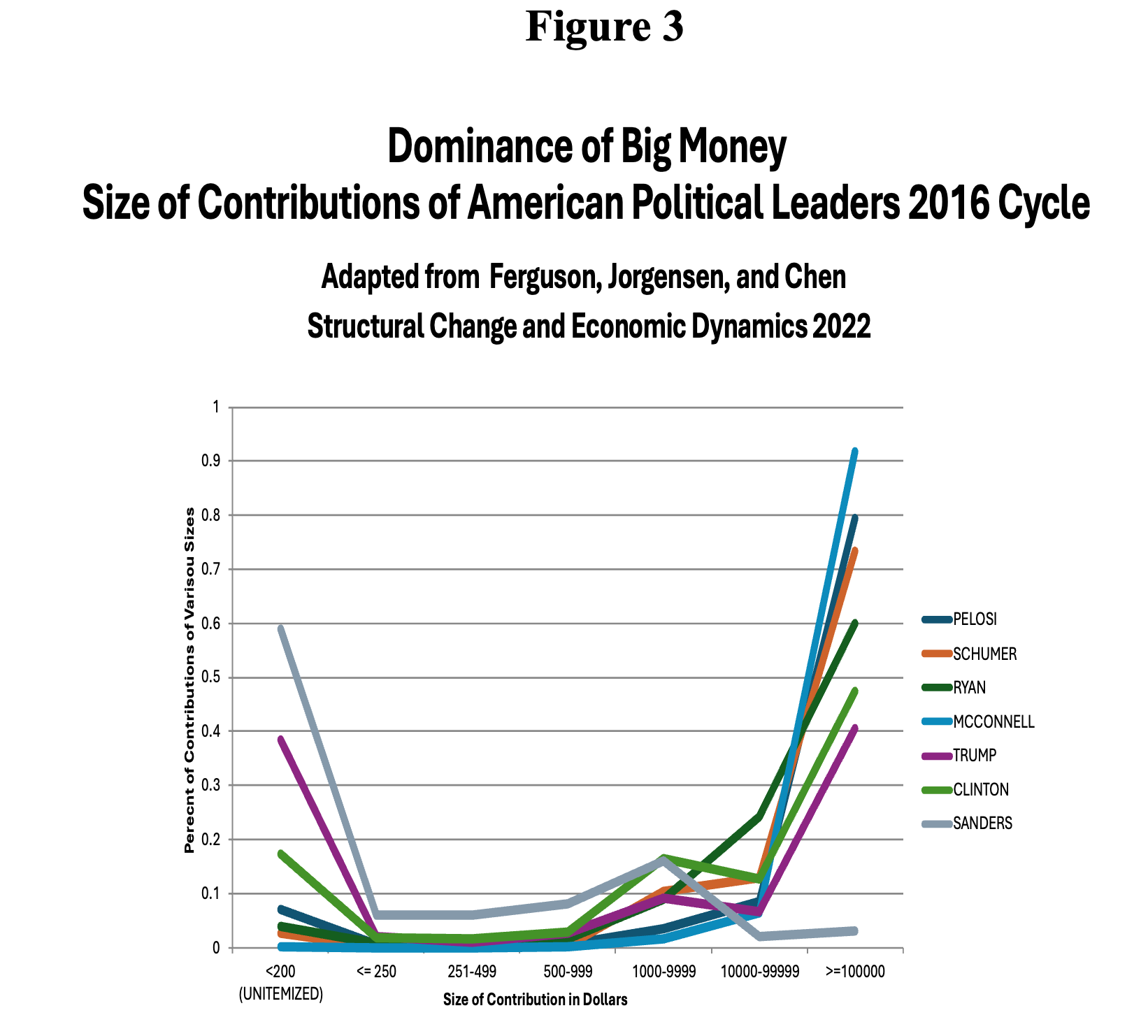

We’ve shown the chart in Figure 3 before because it makes the point very clearly. It’s from the 2016 election, but we believe it still holds true today and thus display it again. (There is no doubt that the new Republican Senate leader fits right in, as our colleague Matthias Lalisse has recently documented.)

Our analysis breaks down big and small donations to the leaders of Congress and presidential candidates in 2016, aggregating them to reveal the real role of big money in bankrolling party leaders.[8]

The main point is clear: Both the presidential candidates and the leaders of both parties in Congress relied heavily on big money donations. The exceptions were Sanders and Trump. Almost no big donors supported Sanders, while Trump’s donations showed an unusual “barbell” pattern—he received large amounts of money from both the very rich and ordinary voters.

Instead of pushing people out of the party, a better and more effective approach is to open up party finances to real transparency and reform. In the New Deal era, grassroots pressure from organized labor — especially the CIO — played a key role in driving bold, popular policies. That didn’t stop big, capital-intensive trade-focused businesses from supporting Roosevelt either.[9]

The issues that matter most to Americans — like Social Security, health care, wages, public health, civil rights, and investment in science and technology –– are widely popular. But if those priorities are going to be protected and advanced, the loudest voices can’t just be lobbyists or donors. The renewal has to come from the mobilization of everyday people. Leaving the future of the parties in the hands of whichever interest groups write the biggest checks isn’t just shortsighted — it’s a recipe for more of the same. Real renewal starts from the ground up, or it will not happen.

Appendix 1

Our statistical methods here follow those in the appendices to Thomas Ferguson, Paul, Jorgensen, and Jie Chen, “How Money Drives US Congressional Elections: Linear models of Money and Outcomes,” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 2022.

For our models we drop races without two major party candidates; see our Structural Change and Economic Dynamics discussion. In many cases those are best viewed as auctions.

Our models are for U.S. House districts and states with Senate elections. All are definite areas in space, with many adjacent to one another. This spatial adjacency can make trouble for statistical analysis, as strong similarities between neighboring areas may signal that the observations are not independent in a statistical sense. As a result, the effective information contained in the data (and our analysis) could be less than what one would expect if the observations were fully independent. In this case, reliance on the usual ordinary least squares regressions (OLS) technique will be misleading.

We thus begin with OLS regressions but then run tests for spatial autocorrelation. In 2024, as in many other cases, these indicated that the House elections were spatially autocorrelated, but that the Senate elections were not. For the latter, OLS regressions suffice.

For the House, to deal with the spatial autocorrelation, we estimate a spatial Conditional Autoregressive model.

Our main text discussed the methods we used to analyze the possibility that the money in elections was simply following polls, along with the event analysis referenced there. But in recent years, as we became familiar with the work of Peter Ebbes and the analysis of that research by Hueter, we have also estimated models that control for endogeneity, that is, the possibility of two-way causality when no plausible instruments are available. Since the Ebbes model had never been extended for cases that were spatially autocorrelated, we developed a version that we could estimate using spatial Bayesian methods – a spatial Bayesian instrumental variable model (SBIV).

We thus report three estimates for the House and two for the Senate: Ordinary least squares estimates for each chamber, followed by the results of the spatial CAR model for the House, and finally, results for our spatial latent instrumental variable (SBIV) regression in the spirit of Ebbes for both. We include R-squared and pseudo-R-squared measures (Nagelkerke’s) for the spatial model.

Appendix Table 1: House and Senate 2024 Data

|

Year |

OLS |

Spatial Model |

SBLIV |

Rsq/Psd |

PV(I) |

N |

|

House |

.719 (.018) |

.686 (.019) |

.689 (.650,.732) |

.806/.821 |

.000 |

393 |

|

Senate |

664 (.064) |

.633 (.501,.785) |

.769 |

.358 |

34 |

Note that

- PV(I) is the p-value of Moran’s I test for the residuals based on an OLS model. For the House data, PV(I) < .05 indicates the need for a spatial model. For the Senate data, PV(I) > .05 suggests that the OLS model is adequate.

- Estimated coefficients and standard errors are reported for the OLS and spatial models, while the median and 75th interquartile range are reported for SBLIV and BLIV models.

The basic lesson from all these is that their results differ only a bit, offering further reason for rejecting suggestions that money is not actually significantly driving elections.

Appendix 2

Our data once again tracks our Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, Vol. 61 (2022): 527-545. We analyze general election races without multiple major-party candidates, which for the House of Representatives yields 423 districts (12 of the 435 districts had races with two Republicans or two Democrats facing each other. Of those 423 districts, 30 had races without a major party opponent, which means our regression analysis contained 393 cases for the House. We kept the House race for Alaska despite a second Democrat on the ballot who garnered 1% of the vote from a federal prison. Our Senate model contained 34 races. After examining the contribution patterns of Dan Osborn in Nebraska and Angus King in Maine, we included them as Democratic candidates and did not drop either race for missing a major party opponent.

For 2024, as usual, we gathered all candidate disbursements and outside money from any source spent in support of the candidate occurring within the entire 2-year cycle, including negative advertising against opponents, to construct the percentage of all money favoring the Democratic candidate in each House and Senate election. We count the money spent on negative advertising as positive money for the candidates that those ads are meant to help. For example, negative ads attacking a Republican are counted as money supporting the Democrat. The campaign spending data derives from multiple Federal Election Commission datasets, containing candidate summary spending totals, independent expenditures (from Super PACs and dark money groups), party coordinated expenditures, electioneering communications (which we examine to clearly identify the support of or opposition to candidates), and communication costs (campaigning internal to some corporations and unions). Note that these include ‘dark money’ totals for each race, but not the real sources of that money. The FEC data and the methodology for calculating total disbursements and “adjusted” disbursements can be accessed here (https://www.fec.gov/data/browse-data/?tab=spending); all outside spending can be extracted from the FEC’s bulk, itemized data accessed here (https://www.fec.gov/data/browse-data/?tab=bulk-data). Adjusted disbursements discount the total for spending that does not directly support the campaign, but using the total or the adjusted figure does not affect the overall analysis. For 2024, we used the adjusted disbursement figure for each candidate to construct our independent variable. The voting data comes from David Leip’s Atlas of US Presidential Elections.

Notes

[1] See Thomas Ferguson, Paul Jorgensen, and Jie Chen, “How Money Drives US Congressional Elections: Linear Models of Money and Outcomes,” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics Vol. 61, June 2022, pp. 527-545. Our first discussions followed the 2012 elections.

Settling on the form of the variable to be explained was a key reason several generations of academic studies missed the relation. They pursued dead ends, such as dollars per vote. Such measures do not scale uniformly in vastly heterogeneous districts.

[2] We also applied recently developed statistical techniques for taking account of potential “two-way” causality (“endogeneity” in social science jargon), further buttress the conclusion. See the discussion in Appendix 1. Not surprisingly, among the first to get our point were some campaign consultants, who realized it meant the number of potentially contestable contests was wider than many analysts believed.

[3] See the discussion of data problems in Ferguson, Jorgensen, and Chen, “Party Competition and Industrial Structure in the 2012 Elections,” International Journal of Political Economy Vol. 42, Issue 2 (2013), pp. 3-41.

[4] We have typically counted money spent against winning primary candidates as benefiting the opposing party in the general election. Common sense recommended the practice, along with the observation that rather a lot of primary races have witnessed ads by the opposing party, not simply intra-party rivals, put forth in the hope of softening up the primary winner for the general election. Possibly reflecting Trump’s efforts to control the party, though, 2024 saw enough Republican primaries to push up totals for some races. The amounts are not large; they just move a few dots slightly on the graph, affecting some outliers. If such cases increase in frequency, it might be advisable to change our practice, but no one should be fooled: money is talking here, loud and clear.

[5] See the discussion in Thomas Ferguson, Golden Rule (University of Chicago Press, 1995), esp. Appendix, “Deduced and Abandoned: Rational Expectations, the Investment Theory of Political Parties, and the Myth of the Median Voter.”

[6] The Appendix to Golden Rule observed that the logic of “competitive” mass media adhered to the same investor-dominated logic as political parties. That point has now become almost embarrassingly obvious, but expanding on it would take us too far afield.

[7] State ballot laws for counting candidates nominated on more than one party line and other apparently technical issues make generalizations hazardous. See the discussion in Ferguson, Golden Rule, Chapter 1.

[8] Virtually all analyses of political money barely scratch the surface when it comes to aggregating contributions by individual contributors. That is why you see so many news stories about a handful of billionaires who are mostly easy to identify. These, we know, underestimate the true concentration levels of big money.

[9] See the discussion in Ferguson, Golden Rule, Chapter 2.