In Treasury markets, there are no libertarians, only grateful recipients of single-payer insurance for ailing financial markets.

“Finance, like time, devours its own children.”

—Honoré de Balzac

Bracket for a moment qualms about the Second Coming’s Cheshire Cat tariff politics and talk of invading Greenland, sweeping up Ukrainian mineral rights, or erecting Mediterranean seaside resorts. Instead, focus on one of the highest-profile pledges President Trump and Vice President Vance made to Joe Rogan and their exultant supporters in high tech and related industries: rolling back globalist “socialism” and severing the choking tentacles of Big Government.

Here, the first impression is strong that the new leadership has really tried to deliver, even if its ballyhooed efforts to trim the federal budget are clearly falling far short of Elon Musk’s promises. As Musk returns to his business interests, DOGE crews have rampaged through one federal agency after another, slashing people and budgets. Not even the famously thrifty Social Security Administration escaped their chainsaw. The Education Department has been downsized and is slated to be phased out. Federal support for science and education is being cut to the bone, along with the State Department, foreign assistance, and even the National Weather Service. The Post Office is being decimated for what looks like a possible privatization down the road, while the administration and Congressional Republicans are reaching an agreement on draconian cuts to Medicaid programs for poorer Americans.[1]

But media impressions can be famously deceiving. They may just point analysts in the wrong direction. Recent events in financial markets raise profound questions about this libertarian resurgence – whether, in fact, a familiar specter famously known for haunting Europe is even now stealing further into American money markets.

Treasury Distemper

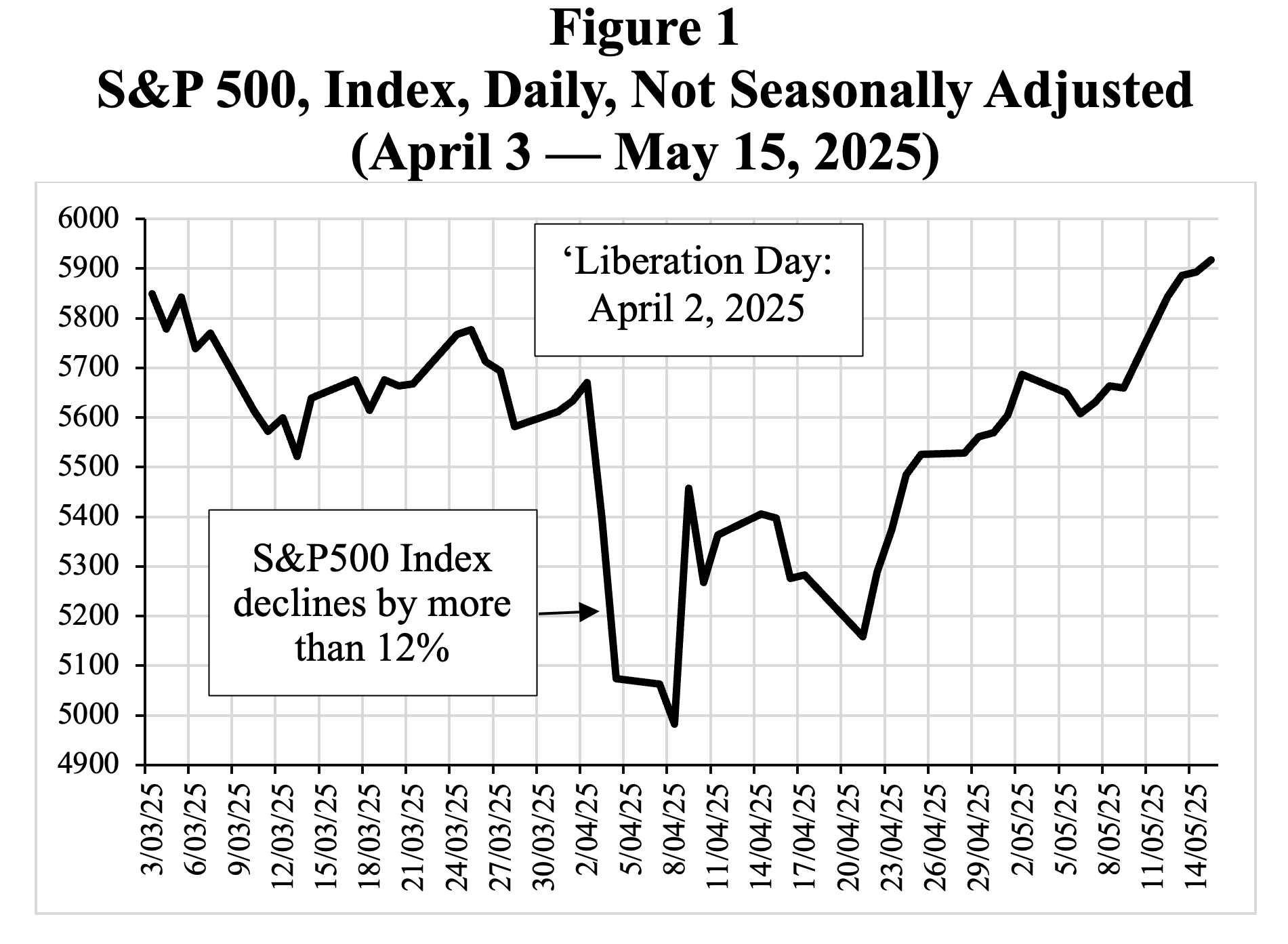

On April 2nd, the President proposed tariffs dramatically higher than most observers expected. Celebrations of “Liberation Day” were cut short, as US and world stock markets cratered (Figure 1). Normally, when vultures circle over equity markets, investors flee into bonds, especially US Treasuries, supposedly the world’s safest asset.

Source: FRED Database.

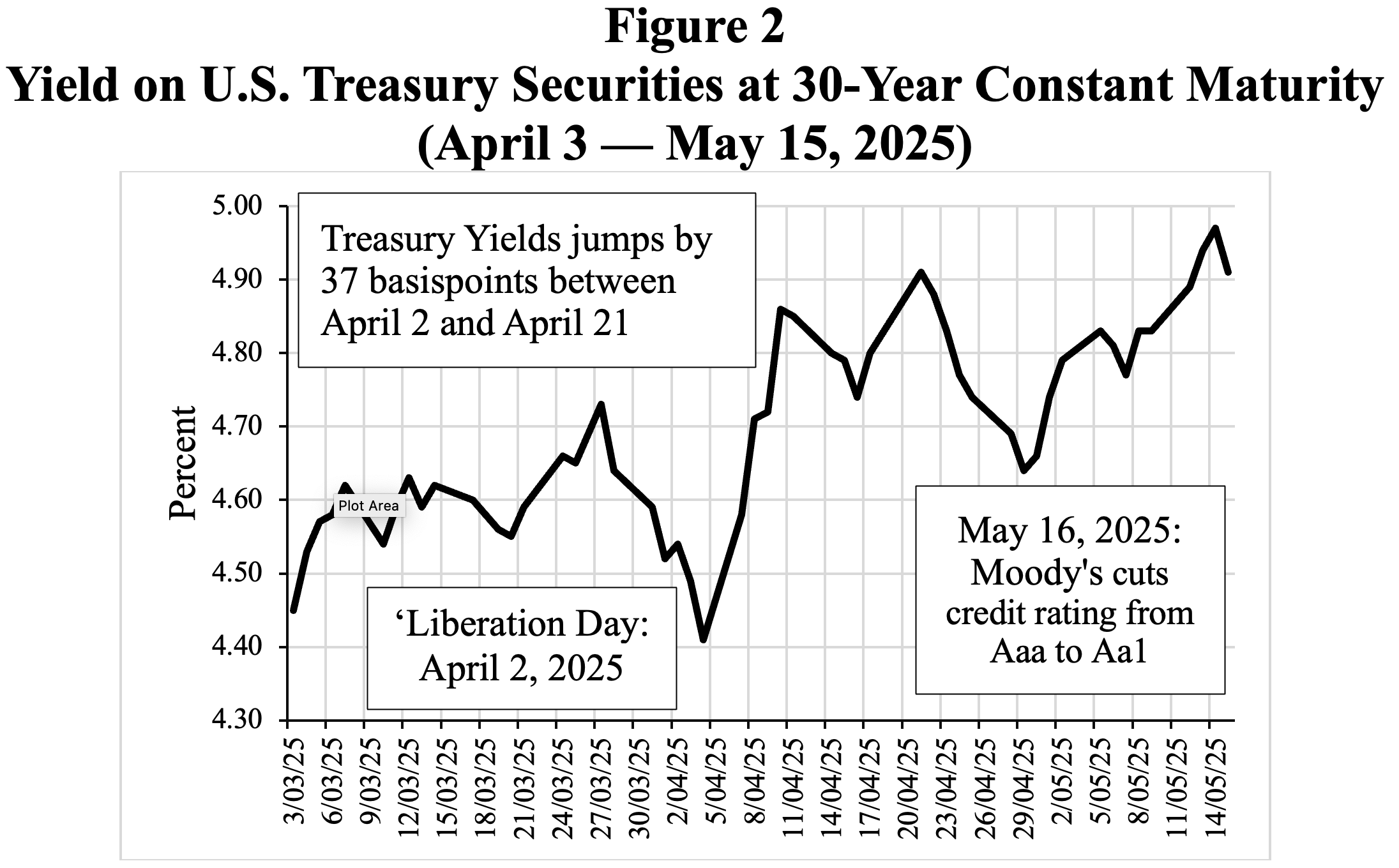

This time, though, bond investors also headed for the exits. Yields on US Treasuries, which go up when their owners sell en masse, shot up (Figure 2). As the London Times reported, by Wednesday of the following week, “the yield on US 30-year bonds had recorded its largest three-day rise in nearly 40 years.” Alarm deepened as word got around that at least one Federal Reserve Bank President with deep experience in financial bailouts was dropping hints that some kind of intervention might be possible, and federal funds futures markets started pricing in Fed emergency action.

Source: FRED Database.

Amid a flurry of reports that tariff-skeptical aides were frantically imploring a course change, the President abruptly called a timeout on April 9th. Explaining that he was “watching the bond market,” which he termed “very tricky,” he put off implementing many – far from all – tariffs for ninety days. Along with a successful Treasury auction of long-term debt, the reversal soothed markets, leading to a rebound in stocks.

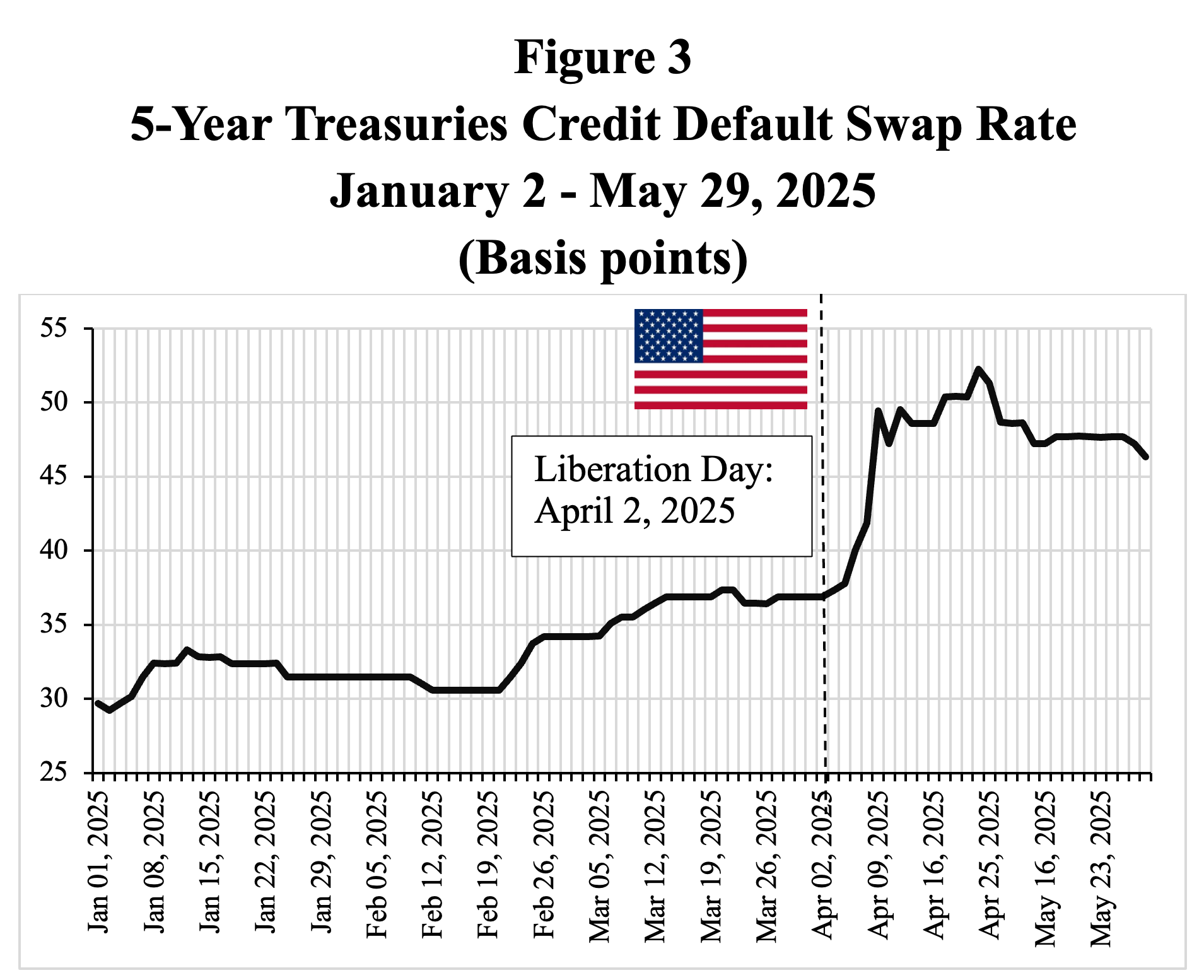

From the start, most media analysts focused on the plunge in stock markets and scorched the tariff decision. But an electric shock also ran through financial markets, as they recognized that something extraordinary was going down in the $28 trillion US Treasury bond markets. Bond investors have clear doubts about the stability of the Treasury market: the price of US credit default swaps — which are supposed to protect bond investors if America fails to honor its debt, and are an indicator of market sentiment — has increased significantly (see Figure 3). On May 16, 2025, Moody’s Ratings cut the US’ sovereign credit rating down one notch to Aa1 from Aaa, the highest possible, citing the growing burden of financing the federal government’s budget deficit and the rising cost of rolling over existing debt amid high interest rates. The turmoil is by no means over.

Source: https://www.investing.com/rates-bonds/united-states-cds-5-years-usd-historical-data .

The key: Continuing financial fragility

The market meltdown in April provoked a riot of claims and counterclaims about exactly what was occurring. A singularly coherent account emerged very early in stories in the London Times and some other papers. Citing economists working in markets and the Bank of England, the Times reported that a “sharp sell-off in US government bonds, known as treasuries, threatens to imperil hedge funds that exploit the small price difference between the spot price of sovereign bonds and bets on their future price — the so-called “basis trade.”

Hedge funds use basis trades to generate an arbitrage profit that should be almost riskless in normal markets.[2] They borrow money (via so-called “repurchase agreements”[3]) to buy an actual Treasury bond while simultaneously agreeing to offload it later by selling a corresponding futures contract.

Customarily, the lender advances a bit less than the value of the Treasury bond to the hedge fund to protect itself against fluctuations in its value, with the difference referred to as a “haircut” on it. The sale of the futures contract by the hedge fund also entails a cost: it advances a modest percentage of the transaction’s total value in cash to the buyer. If financing rates at both ends are reasonably stable, the firm can snag an arbitrage profit.

Interest rate jolts, however, can suddenly turn the paired transactions toxic. Lenders may demand more “margin,” meaning an increase in the cash advanced as security for the repo, along with the Treasury itself. For hedge funds, this can pose a problem. Because the difference, or basis, between spot and futures prices of Treasuries is typically tiny, they typically use large amounts of borrowed money to amplify their bets, so-called “leverage.”

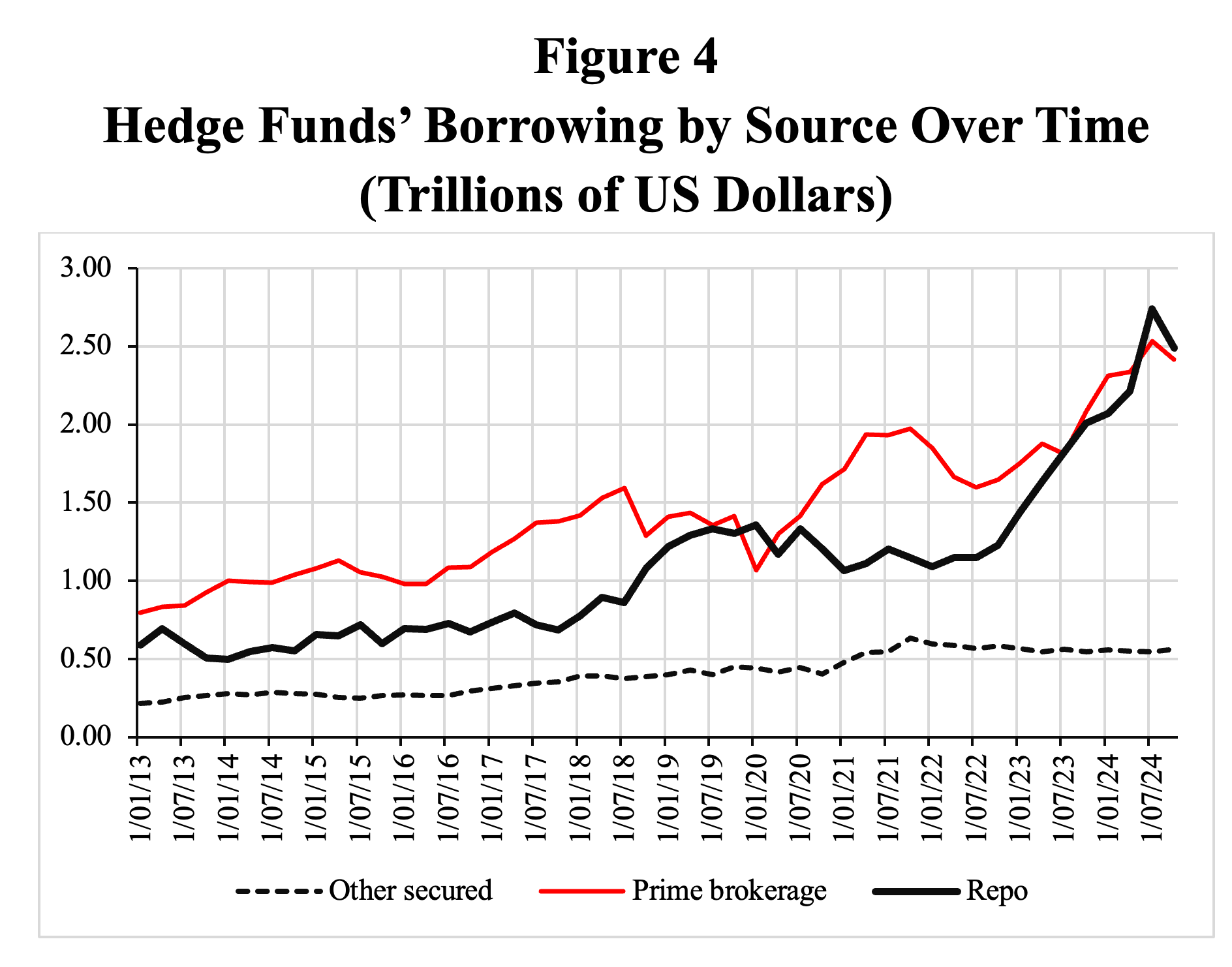

Data suggest that hedge fund leverage in basis markets can range from 50-to-1 or even to 100-to-1, i.e., the funds borrow 50 or 100 dollars for every dollar of their own they have at risk. As can be seen in Figure 4, hedge funds’ borrowing via repos has grown enormously in recent years: from around $0.7 trillion in 2017 to a sizeable $2.7 trillion in the third quarter of 2024. Hedge funds’ net short position in Treasury futures reached $ 1.1 trillion in May (2025), up from $990 billion on April 1 and $434 billion before the onset of the COVID crisis, according to a recent article in the Financial Times of May 22, 2025.

Big, unexpected movements in bond prices, such as the Trump announcement triggered, can thus create serious problems. Demands for more margin in highly leveraged positions can threaten the cash position of the trade, the firm, or, in extremis, a whole sector.

A “former senior Bank of England policymaker” told the Times “that the high leverage — the use of borrowed funds — used by hedge funds to make bets on US bonds, known as treasuries, was one of the reasons for the unusual sharp fall in prices and spike in yields on Wednesday.”

Source: U.S. Office of Financial Research (OFR).

The former central banker zeroed in on an underlying cause of the strange developments: a competitive race to the bottom in financial regulation: “Regulators are not doing enough with respect to containing leverage.” “The US is moving in the opposite direction, and other central banks are being bamboozled by their own banks to follow.”

An account in the Financial Times reinforced the race-to-the-bottom theme even as it raised a yellow flag about the emphasis on basis trades. The piece highlighted a different trade along with runaway animal spirits giddy at the prospect of sweeping financial market deregulation: “At the start of the year, a lot of people were getting excited by the prospect of the new Trump administration unwinding a lot of the post-crisis regulatory edifice…. As a result, hedge funds went long Treasuries and short swaps in the expectation that the spread would flip from being deeply negative to closer to zero. But the convergence trade only works with lots of leverage. And the recent volatility will have ratcheted up margins across the board, forcing some to unwind these trades. That in turn turns the swap spread even more negative, and leads to another round of margin calls, and so on.”

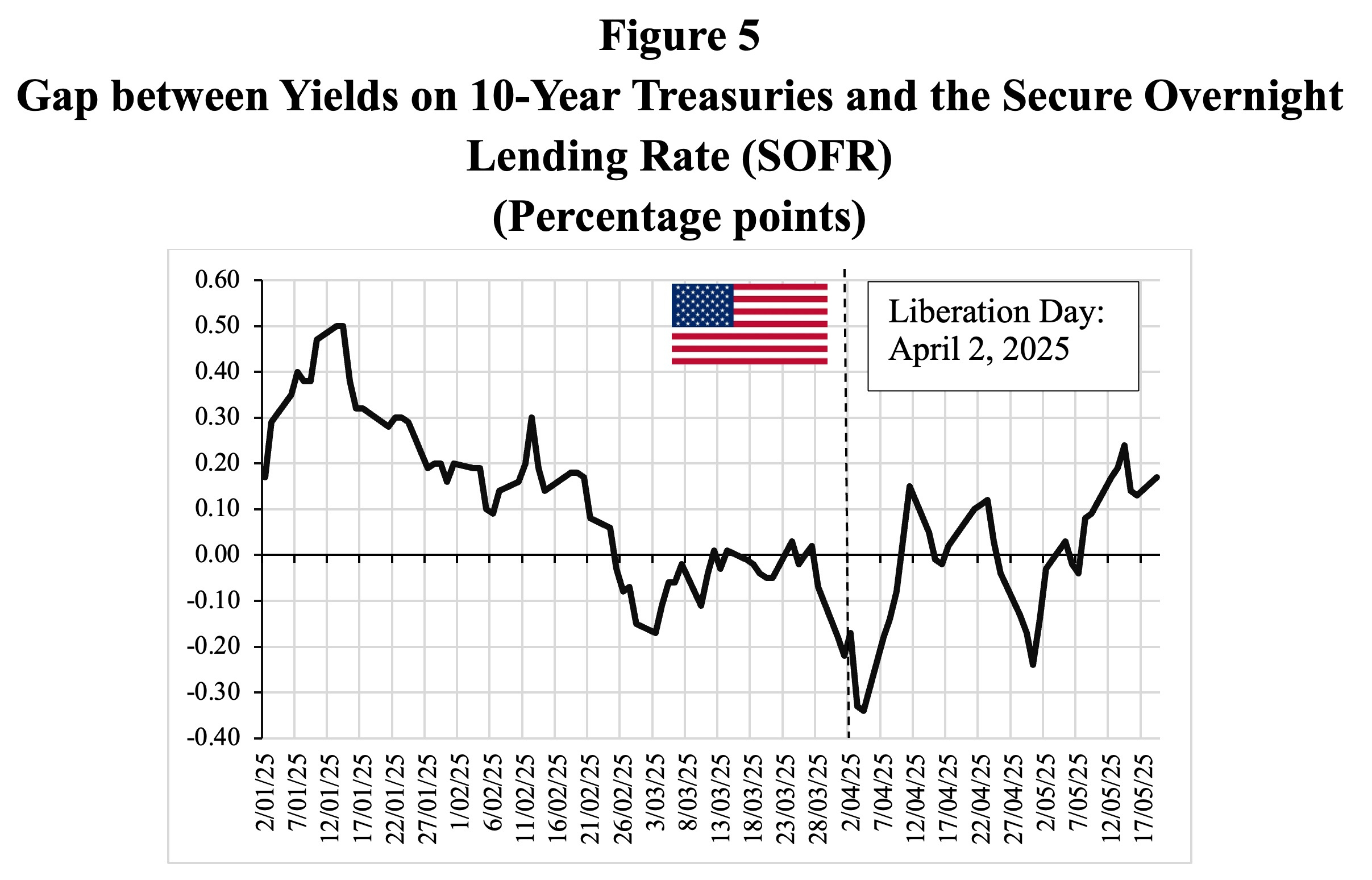

Exhibit A in this account was a rapidly widening gap between 10-year Treasuries and the so-called Secure Overnight Lending Rate (SOFR), as is shown in Figure 5. The inference that actors, likely hedge funds, were selling a lot in a hurry was difficult to avoid.

The diagnosis carried a weighty implication: that not simply the tariff proposals, but elevated financial fragility within the US financial system was a fundamental ingredient in what had just happened. The implications for the Trump administration’s controversial deregulatory agenda for the financial sector were stark.

Source: FRED Database.

The cover-up

Pushback in the media and from finance and politically connected policy makers came quickly. Critics advanced two principal responses. The first was that the whole episode was vastly exaggerated. They insisted on benchmarking the turbulence to the dreaded “dash for cash” that broke out when COVID struck in March of 2020 – a financial market freeze-up that ended only when the Federal Reserve launched a vast new round of quantitative easing and emergency securities purchases. It was a peculiar choice of scale, since analysts wringing their hands over the April market turmoil had plainly stated that the recent turbulence was nothing like the onset of COVID: “we are not nearly there now.”

Citing data from J.P. Morgan Chase, a major primary dealer in Treasuries, the dissenters poured scorn on the notion that Treasury basis trades by hedge funds explained much. A story in the Wall Street Journal, for example, compared complaints about basis trades to a search for a “boogeyman.” It also brushed aside suspicions of any regulatory race to the bottom. In dismissing both possibilities, the piece breezed past acknowledgements that some market developments told in favor of both.

The Journal piece was equally dismissive of the evidence from swaps, concluding that if there were anything really wrong, it was regulatory restrictions on bank leverage. The response reflected a common criticism put forward for some years by Jamie Dimon and many other bankers, that the reforms imposed on banks in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis restrict their ability to step in to fill voids when more thinly capitalized “shadow banks” – hedge funds, high frequency traders, and others that increasingly dominated the market since – become skittish.[4]

Nellie Liang, a former US Treasury official now associated with the Brookings Institution, struck similar notes, though in a less derisive key. She acknowledged that for a few days, the data on interest rate swaps did indeed suggest real turmoil. But she echoed the “not too much to see here” narrative, and its faux comparison to 2020: “available evidence suggests that the current episode so far is not a repeat of the market dysfunction in March 2020.”

She suggested that some credit for April 2025’s happier outcome derived from lessons regulators learned from the earlier disaster. She praised the Fed, the Treasury, and other US regulators for making sure that “much more data on Treasury securities transactions and on hedge funds are being disclosed to the public,” and for introducing other measures to strengthen liquidity within Treasury markets. Among these were a new Treasury “buyback program to allow dealers to sell off-the-run securities on a predictable basis to help free up their balance sheets” and a Fed “standing facility to finance Treasury repo with pre-authorized dealers and banks which could encourage dealers to invest in market-making capacity and support liquidity in times of market stress.”

Despite the increased market transparency, she passed on questions about the role of basis trades or even swaps. She insisted that more data needed to be analyzed before reaching any conclusions. But, remarkably, murky data did not preclude her from avowing that part of the cure might well be to increase the leverage permitted to the very largest banks, specifically by lowering the “Supplementary Leverage Ratio” (SLR) of the big bank holding companies that own the six largest US Treasury securities dealers.[5] The justification, once again, was that rolling back this post-2008 reform would allow banks to absorb more Treasuries coming onto the market.[6]

A recent analysis of the April market turmoil from Robert Perli, head of the Fed’s System Open Market Account. added important twists to the emerging regulatory consensus response. Prefacing his remarks by allowing that “I and my colleagues on the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Desk (the Desk) monitor closely” developments in Treasury market liquidity, Perli also began with a swipe at the March 2020 strawman: “although liquidity in Treasury cash markets became strained in early April, those markets continued to function.”

The question, of course, was how they functioned and their effects on market participants. Here, he offered several interesting observations. Not all are completely persuasive, though, for our purposes, the points of difference are second-order.

We are open-minded, but reserved, for example, about his assurances that hedge fund basis trades counted for little in the April turmoil. Recalling how Fed analyses of the 2020 breakdown initially minimized the role hedge funds played in that, only to be corrected later by a study from the Treasury’s Office of Financial Research, we think future analyses would benefit from direct confrontations with the Bloomberg data presented in Rivas.[7] These indicate a marked widening of the “basis” (the spread between current and future prices crucial to the trade’s profitability) in the run-up to the President’s switch. This must have led to substantial selling.[8] Some other recent Fed accounts of the turmoil also indicate substantial unwinding of leveraged trades by hedge funds during early April.[9]

Moreover, the headline emphasis Perli (and Liang) place on overall market “liquidity” proved to be a poor indicator for understanding the hedge fund behavior in March 2020.[10] Now it is widely accepted that hedge funds unwound vast numbers of basis trades then. These, however, are details that can be left for another time.

Other points in Perli’s analysis are of first-order importance and point to fundamental issues that have so far received less attention than they deserve.

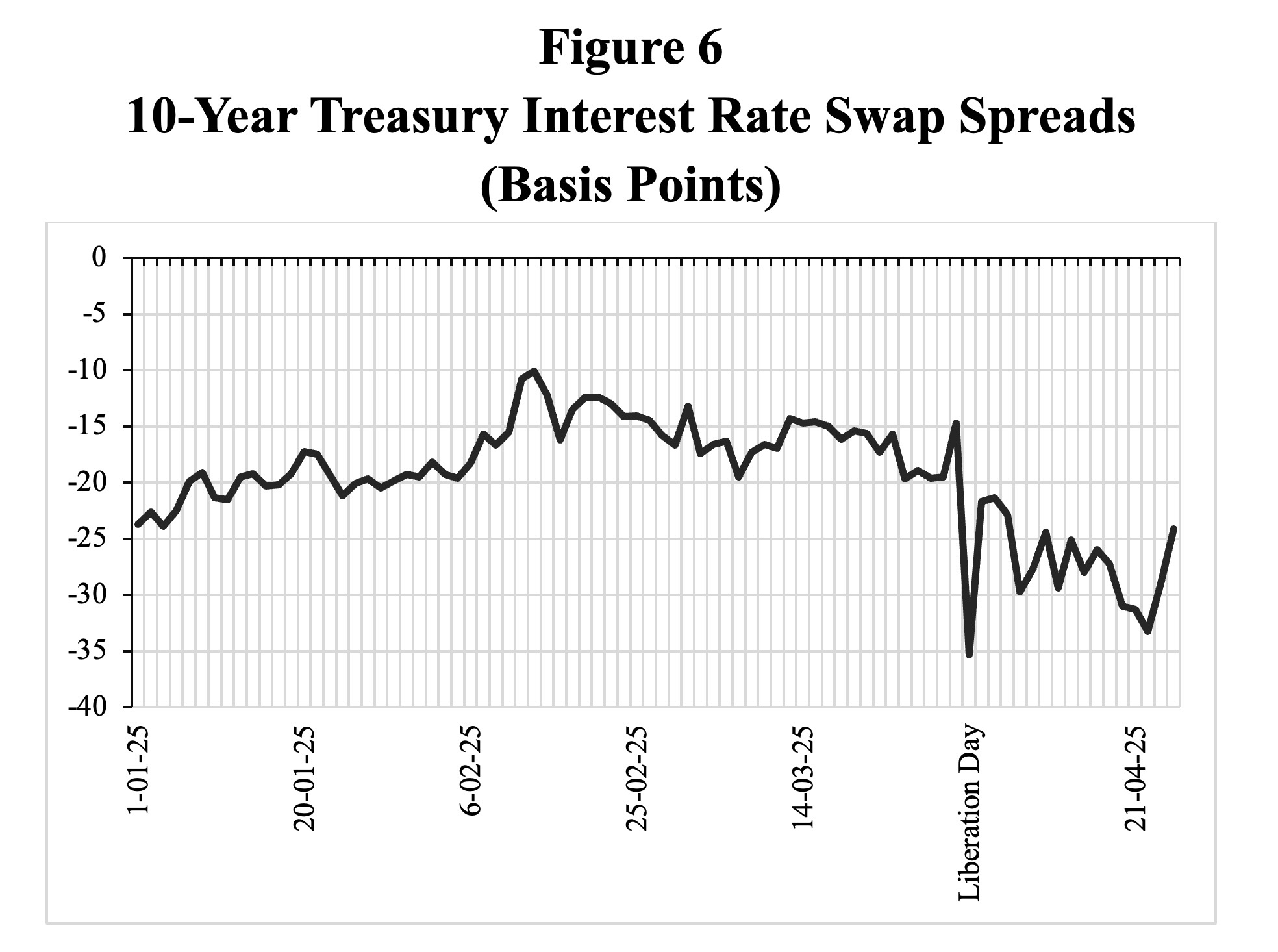

First is his backhanded confirmation of the claim by the anonymous onetime Bank of England regulator in the London Times that visions of deregulatory sugar plums were indeed dancing in the heads of market participants and that those helped destabilize swap prices: “Reportedly, many leveraged investors were positioned to benefit from a decrease in Treasury yields of longer maturity relative to equivalent-maturity interest rate swaps, partially due to the expectation for an easing of banking regulation that would bolster bank demand for Treasuries. Since swap spreads are defined as the swap rate minus the Treasury yield, leveraged investors were making a directional bet that swap spreads would increase.”

The point is illustrated by Figure 6. The 10-Year Treasury interest rate swap spread, which is negative to begin with, rose from circa -20 basis points on January 20, 2025 – President Trump’s inauguration day – to around -15 basis points in early April, 2025, in anticipation of a lowering of the SLR and higher demand for Treasuries. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell also messaged support for a diminished SLR in his semi-annual Monetary Policy Report on February 12, citing the need to bolster liquidity in the Treasury markets.[11]

However, in April, when markets moved adversely, participants bolted for the exits: “The unwinding involved selling longer-term Treasury securities, which likely exacerbated the increase in longer-term Treasury yields.”

Which, of course, led to further downward spirals. The swap spread dropped to -33 basis points on April 22. “Various measures of illiquidity in the Treasury cash market rapidly neared or even exceeded the levels seen in March 2023 during the banking sector stress episode. Importantly, though, they remained well below their March 2020 levels.”

Source: U.S. Office of Financial Research (OFR).

Slouching toward 24/7 single-payer

The extent to which the campaign to downplay the April turbulence is simply a screen to ease a path to further deregulation is an interesting question, but not one we need to resolve here. Bundesbank President Joachim Nagel has since commented that “we experienced considerable turbulence; on certain days, I sometimes felt that we were not far from a meltdown in the financial markets” and warned that strife over tariffs can readily reignite financial markets. We think it is safe to conclude that the early April Treasury market turmoil spotlights real vulnerability in financial markets. Which brings us to Perli’s striking discussion of measures that the Fed is now contemplating for the next disruptions.

His starting point is revealing; indeed, it is all important: An effort to clarify the operational meaning of that Protean term “liquidity.” “I define funding liquidity within the Treasury repo market as the ability to finance existing and new Treasury positions via repos in a timely fashion and at a predictable cost—that is, with little rollover risk. Usually, when funding liquidity is adequate, mispricing across Treasury markets is expected to be limited because investors can finance the transactions to take advantage of arbitrage opportunities.”

As though by an invisible hand, these just happen to be precisely the conditions for profitable massively leveraged trades by banks and hedge funds, high frequency traders, and other players “providing liquidity” in Treasury markets, especially for repurchase agreements (see again Figure 4).[12]

Perli outlines the thinking behind this emphasis: “Funding liquidity is more likely to remain plentiful if money market rates are not too volatile, which, in turn, depends on the availability and efficacy of monetary policy implementation tools for ensuring rate control within the Federal Reserve’s ample reserves framework.”

As tools for such intervention, he emphasizes two Fed facilities for “rate control”: one is the Overnight Reverse Repo Facility (ON RRPF), which “helps put a floor under money market rates by allowing money funds and some other entities to place cash at the Federal Reserve at a predetermined rate.”

The other is the Standing Repo Facility (SRF) set up after the money markets’ March 2020 near-death experience. This “helps support market functioning and dampen upward pressure on money market rates by allowing primary dealers and certain depository institutions to obtain liquidity from the Federal Reserve at a rate equal to, or potentially slightly higher than, the facility’s minimum bid rate.”

This brings us to the heart of the matter: In times of war, military chaplains were fond of repeating that there were no atheists in foxholes. We must conclude that nowadays, in Treasury markets, there are no libertarians, only grateful recipients of single-payer insurance for ailing financial markets.

The conclusion is reinforced by other happy news that Perli delivered: that another round of what would in any other context be decried as state socialism is imminent: “The SRF is an important part of the Federal Reserve’s toolkit, particularly when liquidity conditions tighten….we are always evaluating its parameters….As part of this evaluation, the Desk has conducted technical exercises that consisted of morning SRF operations that also settle in the morning, carried out in addition to the long-standing operations that take place and settle in the afternoon.”

At a time when many prominent Wall Street executives were cycling like Glockenspiel figurines in and out of the major media warning of the need for cuts in government, Perli reported enthusiastically that money markets were thumbs up on the Fed’s proposals.[13]

His desk’s “market outreach following the March quarter-end revealed that primary dealers see the early-settlement SRF operations as an enhancement that increases the likelihood that the SRF will be used when economically convenient to do so….Dealers also reported that early settlement lowers hurdle rates—that is, the rate in excess of the SRF rate they are willing to pay in the market before choosing to access the SRF.”

Thus encouraged, Perli assured his audience that the Fed “plans on making early-settlement SRF auctions part of the regular SRF daily schedule, at some point in the not-too-distant future.”

But there was more. Perli promised further visits from Santa Claus to the markets. “This does not mean that there won’t be room for further improvement…. Notably, reported hurdle rates in the tri-party repo market segment, where the SRF operates, are materially higher than the SRF rate. In other words, our counterparties tell us that they need to see market rates somewhat above the SRF rate before being willing to access the facility…Where possible, Federal Reserve staff will continue to look for ways to improve the efficacy of the SRF.”

Whether the new Fed gift package will arrive in time for Christmas, when the President has suggested that many American children may well be making do with notably fewer dolls than before, is not a simple question. Despite the blithe assurances, it is apparent that policy circles are evaluating a rich menu of options for aiding financial markets in general and repos in particular beyond those Perli mentioned.

In the last few years, increasing numbers of analysts have noticed that the market for “Treasury securities has faltered repeatedly since late 2008.” The 2020 and April 2025 cases discussed here are but two; 2019 witnessed considerable turmoil, 2023 was another. That last provoked astonishment from many outside analysts who worried that

The Federal Reserve risks moving beyond its role as a lender of last resort to a prop that markets need to function even in normal times….

The latest sign of the Fed’s mission creep came on Sept. 30, when typical end-of-the-quarter strains on Treasury markets led to a $2.6 billion drawdown of its funding backstop, called the Standing Repo Facility (SRF), since it was set up in 2021 after a market scare.

The facility, which allows some lenders to borrow against collateral such as Treasuries, was set up to alleviate cash shortfalls in the market, which can lead to sudden spikes in short-term interest rates that threaten financial stability.

But two banking sources who requested anonymity to speak candidly and a market expert told me there was no liquidity problem that day, and indicators of financial stress were below normal levels.

Instead, these people said the drawdown highlighted a potent structural issue: At about $28 trillion, the Treasury market has become too large….

Already, the Fed and market participants are floating ideas that would pull the central bank even deeper into markets, ranging from centrally clearing some transactions to broadening who can borrow from it and offering the SRF earlier in the day.[14]

This is the real context of the policy discussions now in progress. With swelling federal government debt available for repos, 2023’s wave of bank failures, and the thin capitalization of so many shadow banks, underlying anxieties about money market fragility were intensifying well before the April turbulence. And we are sure that the Bundesbank President is not the only person worrying about what happens next.

Only days before the President’s announcement, for example, the Brookings Institution published a paper by four senior economists, including a former Federal Reserve governor, reviewing proposals for guaranteeing liquidity in Treasury markets. Their favorite would create yet another Fed facility to provide 24/7 surveillance and possible intervention in repo markets. The authors are not blind to the possible moral hazards that come with single-payer insurance, though we do not believe their proposed mechanism is as antiseptic as they suggest. But to term this a straw in the wind is an understatement: it is more like a telephone pole sailing by in a hurricane.

It is obvious that in financial markets the whole is now far more vulnerable than the various parts – and that all too many of the latter are reminiscent of fantasy concoctions dreamed up by a financial engineering team captained by Lewis Carroll and Hieronymus Bosch.

For example, amid all the handwringing over thinly capitalized and opaque shadow banks, those are now far more intertwined with the regular banking system than usually recognized. Crypto is also waiting in the wings, certain to import a wild, toxic array of new hazards into the banking system. And in an increasingly belligerent multi-polar world economy, routine leverage rates of 50 or 100 to 1 are a virtual invitation to disaster: Today tariff threats, tomorrow, somebody’s border claims, or climate disaster, or carry trade reversals can abruptly disrupt everyone’s calculations. We know, because they already have.

There is also the looming question of how the deep tensions between the Federal Reserve and the White House will be resolved when Jerome Powell’s term as Fed Chair runs out less than a year from now.

Sorting through hazards to safe assets in such a world requires explicit consideration of state policies regarding industrial leadership and alliances as well as domestic politics. In such a world, the system’s stability cannot possibly be enhanced by reducing capital requirements for the biggest, most systemically important financial institutions. This is hope that only money-driven political systems could possibly indulge. This dream will very likely turn into a nightmare, because easing the SLR for the biggest banks and dealers in the Treasury market is likely also to encourage the already highly-leveraged hedge funds — the very fragilities that policymakers claim to be mitigating.

The glaring gap: finance and the real economy

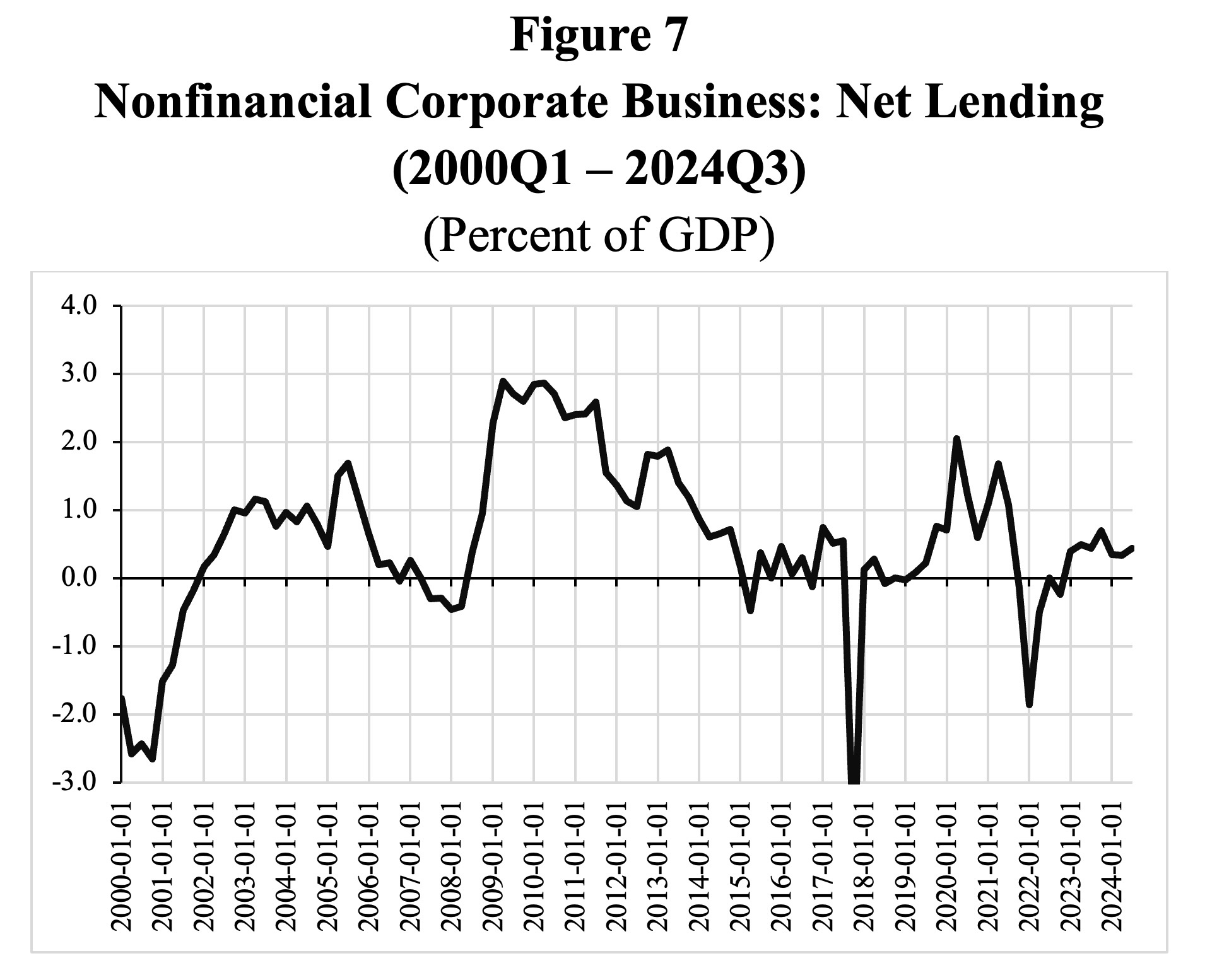

The traditional justification for intermediation in financial markets is its importance for real capital formation. A first point to note is that US non-financial corporations are net lenders, in a macroeconomic sense, because their (high) profits exceed their fixed investments (see Figure 7). This means that the need of (often cash-rich) non-financial corporations for financial intermediation is rather limited, at least at the aggregate level.

Source: FRED Database.

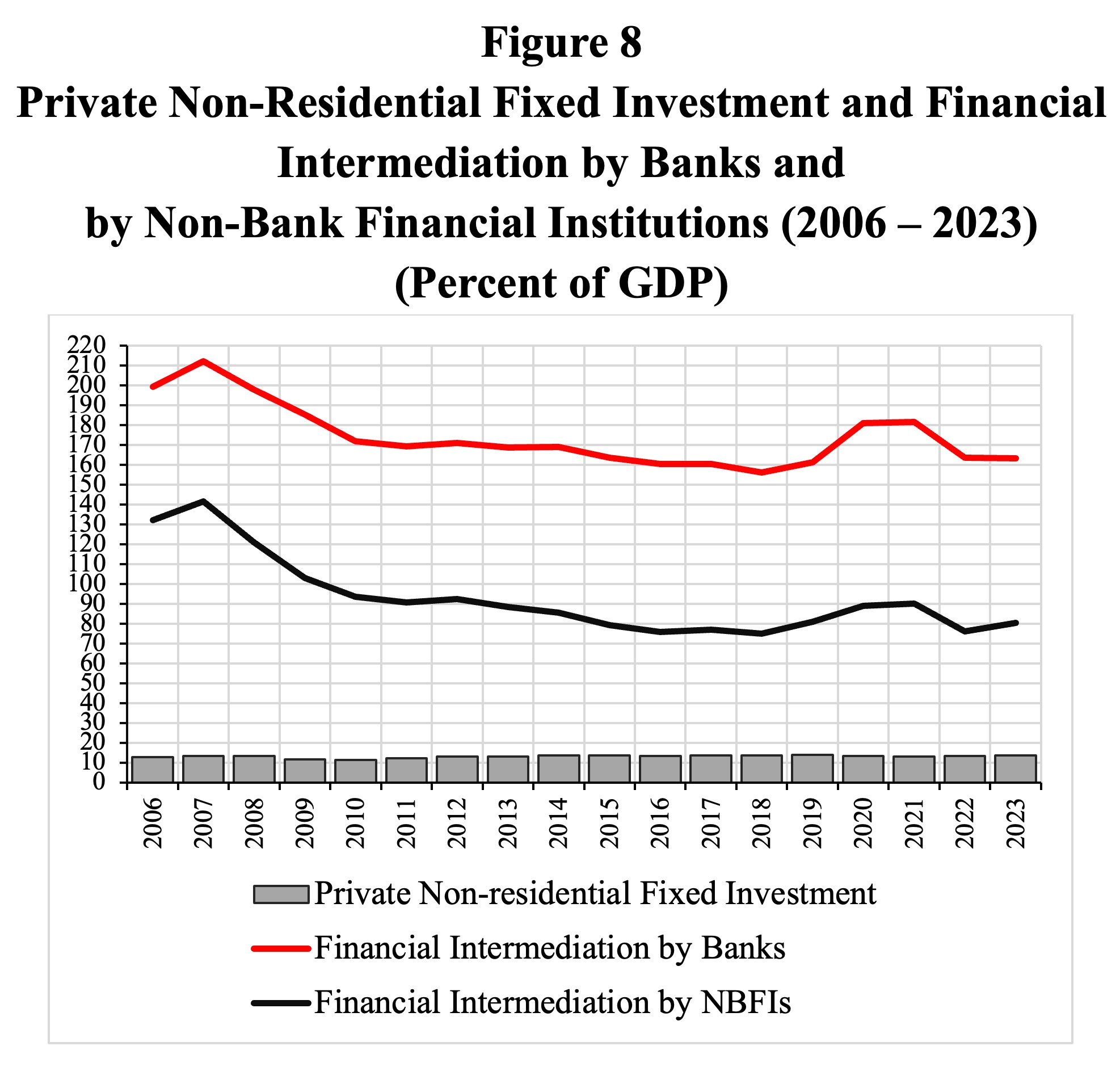

Not that this has stopped the financial sector from expanding exponentially. As shown in Figure 8, the assets of US non-bank financial institutions (aka “shadow banks”) which consist of loans and financial investments, equaled around 93% of American GDP during 2006-2023, while the assets of commercial banks add another 81% (on average); hence, the total scale of financial intermediation is around 174% of GDP, while private non-residential fixed investment summed to only 13% of GDP. It is evident that the bulk of (shadow-bank) financial intermediation in the US does not serve real capital formation in any real sense.[15]

Sources: Financial Stability Board, Database on Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation; FRED Database Notes: The red line shows the sum of bank and NBFI intermediation (as a percentage of GDP). The non-bank financial intermediation (NBFI) institutions include money market mutual funds (MMFs), hedge funds, broker-dealer firms, insurance companies, securitization-based credit intermediation, and other finance firms.

As mentioned earlier, banks and shadow banks are also working and growing closely together. Instead of lending directly to firms, commercial banks are now lending to non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs), which then often lend to the same underlying non-financial corporations (in the aggregate). In fact, as reported by Robin Wigglesworth (2025) in the Financial Times (May 29), commercial bank lending to “these NBFIs has quintupled over the past decade to well over $1tn, and now accounts for more than 10 per cent of all US banking loans (and nearly 5 per cent of all assets).”[16] By lending to non-banks, instead of to firms, commercial banks slip around capital requirement rules: the risk-weighted capital requirements on “Commercial and Industrial Loans” to firms are much higher than the capital requirement on NBFI loans. By evading regulation in this way, the banks provide additional leverage, and as their NBFI lending grows, so too does overall leverage and systemic risk in the financial industry.

The glaring contrast between bourgeoning financial paper and real capital formation is making the claim that finance serves the real economy, to the extent it was ever true, look quite threadbare. The astronomical gross flows surging through contemporary money markets are at most only obliquely related to real economic activity; a high percentage, probably most, originate in efforts to hedge hazards that the process itself, with all its leverage and tiny margins, creates.

Socialism for the Rich

Ever since the post-2008 reforms, financiers have been fighting and spending vast sums on lobbying, political contributions, and revolving doors, to undermine them. They now believe that they stand on the brink of total victory. But piling up of risks and leverage, as the world economy restructures, guarantees a never-ending succession of shocks with the potential to spiral out of control. The result is the precise opposite of free markets: an ever heavier and more obtrusive hand intervening to secure an infinity of profitable transactions for a select few with access to credit, regulatory connections, and the resources required to dominate legislatures and executives.

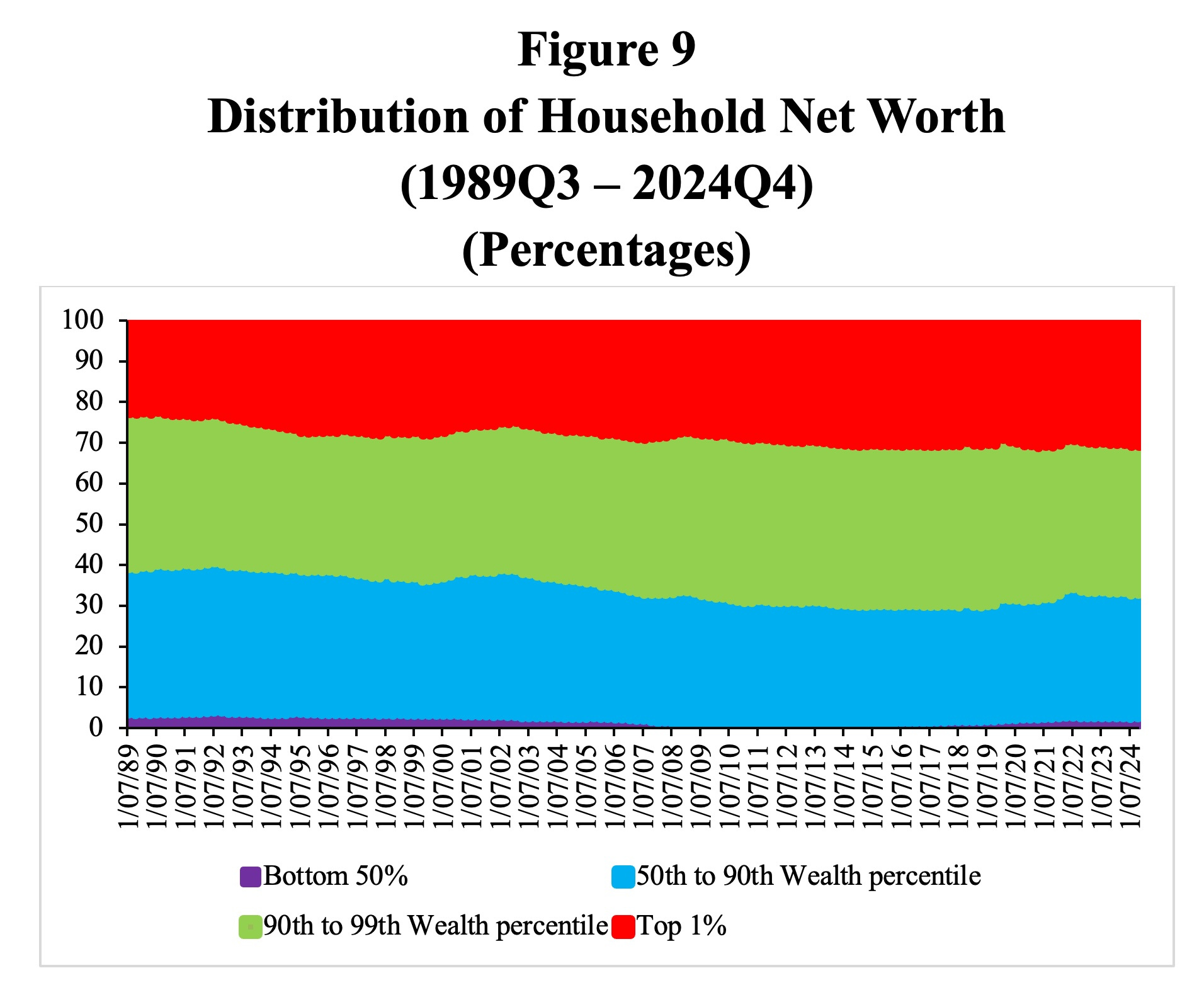

We are witnessing the slow-motion extension of single payer insurance for financial markets, pure and simple, and the perfection of a stunning world-class machine for extracting resources from everyone else. This apparatus makes finance effectively a “heads I win, tails you lose” business: the implicit backstop provided by the Federal Reserve provides banks and now, more and more, shadow banks, with many advantages, ranging from tailored bailouts to enhanced credit ratings and lower financing costs while incentivizing them to undertake risky transactions. By extracting rents from public safety nets, the financial sector is helping the super-rich to prop up their disproportionate share in household wealth, while disempowering the bottom 50% or more American households. As Figure 9 shows, the wealthiest 10% of US households manage to capture more than two-thirds of household net wealth, and the wealthiest 1% claim more than 30% of household net wealth. To do so, the wealthiest need the state.

Source: FRED Distributional Financial Accounts.

The rich and powerful champion free markets only rhetorically. They want to be able to run their own nanny state so that when they are in trouble, the Fed or taxpayers will bail them out directly. The idea that Bernie Sanders is the most prominent socialist in the US is all wrong.

References

Acharya, V.V., N. Cetorelli and B. Tuckman. 2024. “Where Do Banks End and NBFIs Begin?” NBER Working Paper 32316, Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w32316

Acharya, V.V. and T. Laarits. 2025. “Tariff War Shock and the Convenience Yield of US Treasuries – A Hedging Perspective.” Mimeo. University of New York, Stern School of Business, April 23. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5229097#:~:text=This%20note%20explains%20how%20the%20%22tariff%20war%22%20shock,a%20rising%20stock-bond%20covariance%20computed%20using%20intraday%20data.

American Bankers Association. 2025. “Post on X,”April 9. Link: https://x.com/ABABankers/status/1909943479494377657

Bair, S. 2019. “Why Banks Shouldn’t Blame the ‘Repo Rupture’ on Regulation.’”Yahoo! Finance, October 18. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/sheila-bair-repo-market-malfunctions-143450318.html

Bansal, P. 2024. “In the Market: Banks Warily Warm Up to Fed Repo Backstop.” Reuters, February 27. https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/market-banks-warily-warm-up-fed-repo-backstop-2024-02-27/

Bansal, P. 2024. “In the Market: How Harris, Trump Promises Could Feed Market’s Addiction to the Fed.” https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/market-how-harris-trump-promises-could-feed-markets-addiction-fed-2024-10-30/

Barth, D. and J. Kahn. 2020. “Basis Trades and Treasury Market Illiquidity.” OFR Brief Series 20-01, July 16. Washington, DC: Office of Financial Research. https://www.financialresearch.gov/briefs/files/OFRBr_2020_01_Basis-Trades.pdf

Cochran, P., S. Infante, L. Petrasek, Z. Saravay and M. Tian. 2023. “Dealers’ Treasury Market Intermediation and the Supplementary Leverage Ratio.” FEDS News, August 3. Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/dealers-treasury-market-intermediation-and-the-supplementary-leverage-ratio-20230803.html

Committee on Capital Markets Regulation. 2023. “An Overview of the Treasury Cash-Futures Basis Trade.” Washington, DC. https://capmktsreg.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/An-Overview-of-the-Treasury-Basis-Trade-12-20-23-FINAL.pdf

D’Innocenzio, A. and D. Tang. 2025. “Two Dolls Instead of 30? Toys Become the Latest Symbol of Trump’s Trade War.” AP, May 9. https://apnews.com/article/trump-two-dolls-tariffs-toys-7b0e5d3a9035471317e6dc4ee1fbfbc1

Du, W. 2025. “A Mooted Fix for the Treasury Market May Actually Increase Systemic Risk.” The Financial Times, May 22. https://www.ft.com/content/4786286e-1585-4e14-b9fc-e9872b0e1490

Federal Open Market Committee. 2024. “Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee April 30–May 1, 2024.” Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/fomcminutes20240501.pdf

Federal Reserve. 2025. Financial Stability Report April 2025. Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/financial-stability-report-20250425.pdf

Federal Reserve Bank of New York. 2025. “Household Debt and Credit Report Q1 2025.” Center for Microeconomic Data, Federal Reserve Bank of New York. https://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/hhdc

Ferguson, T., P. Jorgensen, and J. Chen. 2020. “How Much Can the U.S. Congress Resist Political Money? A Quantitative Assessment.” Institute for New Economic Thinking Working Paper Series No. 109. New York: Institute for New Economic Thinking. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3593916

Financial Stability Board. 2025. “Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation: Data.” https://www.fsb.org/work-of-the-fsb/financial-innovation-and-structural-change/non-bank-financial-intermediation/global-nbfi-monitoring-report-data/

Fischer, A. and Ph. Basil. 2025. “The Basis Trade: Financial Fragilities Exposed by Tariff Chaos.” Tariffs Fact Sheet. Washington, DC: Better Markets. https://bettermarkets.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Basis-Trade-Fact-Sheet-4.10.25.pdf

Goodkind, N. 2025. “The Treasury Market Is Sending Alarms. Here’s How the Fed Could Help.” Barron’s, April 9. https://www.barrons.com/articles/treasury-market-yields-alarm-federal-reserve-intervention-7d9979ab

Hancock, E. and E. Vardon. 2025. “EU to Delay Bank Trading Desk Rules for Second Time.” The Wall Street Journal, May 23. https://www.wsj.com/finance/regulation/eu-to-delay-bank-trading-desk-rules-for-second-time-81622abf?mod=author_content_page_1_pos_4

Hildebrand, J. 2025. “G7-Partner warnen vor Trumps Zollpolitik.“ Handelsblatt, May 22. https://www.handelsblatt.com/politik/deutschland/finanzministertreffen-g7-partner-warnen-vor-trumps-zollpolitik/100129528.html

Hosking, P. 2025. “Central Banks Under Pressure to Tighten Leverage Rules for Hedge Funds.” The Times, April 10. https://www.thetimes.com/business-money/economics/article/central-banks-under-pressure-to-tighten-leverage-rules-for-hedge-funds-xqlj2h92c?msockid=344f0524d2426e223edf104fd3f26f3e

Hurley, James. 2025. “UK Economy at Risk of Shock, Warns Bank of England.” The Times, April 9. https://www.thetimes.com/business-money/economics/article/bank-of-england-uk-at-risk-of-economic-shock-0ml3sqd7t?msockid=344f0524d2426e223edf104fd3f26f3e

Hurley, James and M. Kahn. 2025. “Hedge Fund Strategists Count the Cost of Donald Trump’s Trade War.” The Times, April 9. https://www.thetimes.com/business-money/companies/article/hedge-fund-strategists-count-the-cost-of-donald-trumps-trade-war-ms72t9d2d?msockid=344f0524d2426e223edf104fd3f26f3e

Kane, E.J. 2019. “Repo Madness: Fed Plumbing Gone Awry.” INET Blog, November 26. New York: Institute for New Economic Thinking. https://www.ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/repo-madness-fed-plumbing-gone-awry

Kashyap, A.K., J.C. Stein, J.L. Wallen and J. Younger. 2025. “Treasury Market Dysfunction and the Role of the Central Bank.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity Conference Draft, Spring. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/4_Kashyap-et-al.pdf

Krugman, P. 2025. “The Trade War Isn’t Over.” Substack, May 16. https://paulkrugman.substack.com/p/the-trade-war-isnt-over

Liang, N. 2025. “What’s Going on in the US Treasury Market, and Why Does It Matter?” Commentary, Brookings Institution, April 14. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/whats-going-on-in-the-us-treasury-market-and-why-does-it-matter/

Marte, J. 2021. “Fed Establishes Standing Repo Facilities to Support Money Markets.” Reuters, July 28. https://www.reuters.com/article/business/fed-establishes-standing-repo-facilities-to-support-money-markets-idUSKBN2EY2OR/

Mascaro, L. 2025. ‘House Republicans Unveil Medicaid Cuts that Democrats Warn Will Leave Millions Without Care.’ AP, May 12.

Menand, L. and J. Younger. 2023. “Money and the Public Debt: Treasury Market Liquidity as a Legal Phenomenon.” Columbia Business Law Review, vo. 2023 (1). https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/CBLR/article/view/11900

Moody’s Analytics. 2025. “Moody’s Ratings Downgrades United States Ratings to Aa1 from Aaa; Changes Outlook to Stable.” Ratings News, https://ratings.moodys.com/ratings-news/443154

Pellerin, S. 2024. “Bank Capital Analysis Semi-Annual Update.” Bank Capital Analysis. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, October 24. https://www.kansascityfed.org/Banking/documents/10556/Bank_Capital_Analysis_Report_-_2Q_2024_-_final.pdf

Perli, R. 2025. “Recent Developments in Treasury Market Liquidity and Funding Conditions.”Remarks at the 8th Short-Term Funding Markets Conference, Federal Reserve Board, Washington, DC, May 9. https://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/speeches/2025/per250509

Powell, J.H. 2025. “Hearing Entitled: The Federal Reserve’s Semi-Annual Monetary Policy Report.’”Hearings. Washington, DC: United States House Committee on Financial Services, February 12. https://financialservices.house.gov/calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=409453

Rivas, D. 2025. “Basis Trades: The Hidden Amplifier Behind 2025’s Treasury Market Turbulence.” Hidden Alpha Blog, April 10. https://hiddenalpha.blog/2025/04/10/basis-trades-the-hidden-amplifier-behind-2025s-treasury-market-turbulence/

Sindreu, J. 2025. “The Simple Explanation for this Week’s Treasury Market Mayhem.” Wall Street Journal, April 11. https://www.wsj.com/finance/investing/the-simple-explanation-for-this-weeks-treasury-market-mayhem-9351f339?msockid=344f0524d2426e223edf104fd3f26f3e

Sutton, S. and V. Guida. 2025. ‘‘Trust is going down’: Why Trump Should Fear the Bond Market.’ Politico, April 11. https://www.politico.com/news/2025/04/11/trust-is-going-down-why-trump-should-fear-the-bond-market-00285533

Tapia, J.M., R. Leung, and H. Hamandi. 2024. “Banks’ Supplementary Leverage Ratio.” OFR Blog, Office of Financial Research, August 2. https://www.financialresearch.gov/the-ofr-blog/2024/08/02/banks-supplementary-leverage-ratio/

Tooze, A. 2020. “Revisiting The Role of Hedge Funds in the March 2020 Treasury Market Turmoil.” Chartbook Newsletter #7, Substack, December 7. https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/chartbook-newsletter-7

Wigglesworth, R. 2025. “An Emergency Rate Cut From the Fed.” Financial Times, April 9. https://www.ft.com/content/e8b55c84-aadc-49fa-9746-8e9d23b5bef8

Wigglesworth, R. 2025. “The Trades Threatening the Treasury Market.” Financial Times, April 9. https://www.ft.com/content/6e6261e1-42bd-4cca-827e-218c111a6432

Wigglesworth, R. 2025. “The $1Trillion Shadow Bank Lending Boom.” The Financial Times, May 29. https://www.ft.com/content/b7729107-afb1-4fd7-bfd2-434d1ef7edbb

Wigglesworth, R., K. Duguid, C. Mourselas, and I. Smith. 2025. “How the Treasury Market Got Hooked on Hedge Fund Leverage. Financial Times, April 25. https://www.ft.com/content/0bf5bcc2-6ff1-4309-afbf-f470250a4721

Endnotes

The authors benefited from comments by very helpful colleagues with widely diverse views. Our thanks to Phillip Basil, Robert McCauley, Perry Mehrling, and Walker Todd for careful readings and comments. We also owe a longer-term debt to the late Edward J. Kane, whose study of the 2019 repo controversy we are especially gratified to reference.

[1] The Senate has yet to act on the bill, and many changes have been proposed, as demands for bigger cuts become more intense as a result of bond market anxieties. Fears of voter anger at the cuts also run high. As this paper appears, the proposal is to cut Medicaid and other social programs by approximately $880 billion to help cover the cost of $4.5 trillion in tax breaks. According to a preliminary estimate from the Congressional Budget Office, the proposals would reduce the number of people with health care by 8.6 million in 2034.

[2] Nomenclature in financial markets is not precise, for more reasons than we have time to discuss here. That is true even for apparently standardized classifications used by regulatory bodies in different countries. In practice, the label “hedge fund” shades insensibly over to embrace high frequency trading and other activities. And trades involving securities other than Treasuries carry much higher risks.

[3] The name is confusing. Repurchase agreements are economically loans, with the twist that the borrower actually sells the collateral for the loan to the lender for a short period, promising to buy it back at a slightly higher price. That becomes the lender’s profit. Compare with loans from a pawnshop. In those borrowers’ deposit something valuable with the lender, but continue to legally own it as long as they repay. In the basis trade, the treasury bill is itself the collateral, though with, crucially, an extra margin of cash that can change with market conditions.

[4] The main domestic legislation was the Dodd-Frank bill, enacted in 2010. US regulators coordinated with international regulators in several rounds of “Basel agreements.” The US has not ratified the Basel III accords and with the change in administrations likely never will. As this piece goes to press, EU regulators are announcing postponement of some of their own Basel 3 reforms on the grounds that they might disadvantage European banks.

[5] The SLR is a non-risk weighted capital requirement, which is particularly affected by high-volume, low-risk activities such as Treasury market intermediation. For the biggest banks, especially those with large dealer subsidiaries, the SLR rule has implied higher capital requirements than risk-based capital rules in recent years, restricting their willingness and ability to intermediate in Treasury markets. As a result, the market for Treasuries becomes more dependent on intermediation by shadow-bank firms including hedge funds who have picked up the role of banks and their dealer subsidiaries.

Banks subject to specific Federal Reserve’s prudential standards must maintain an SLR of at least 3%. However, the eight US globally systemically important banks (which do not all own major dealers) are subjected to an enhanced SLR, which effectively requires them to maintain an SLR well above the minimum level of 5% (see Table 1). This, they feel, is unduly hurting their businesses.

Table 1

U.S. Global Systemically Important Banks: Assets and SLRs

(2024, second quarter)

|

|

Total assets ($ billions) |

SLR (%) |

|

Bank of America Corporation |

3258 |

5.98 |

|

Bank of New York Mellon Corporation |

429 |

6.83 |

|

Citigroup Inc. |

2406 |

5.89 |

|

Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. |

1653 |

5.45 |

|

JPMorgan Chase & Co. |

4143 |

6.09 |

|

Morgan Stanley |

1212 |

5.46 |

|

State Street Corporation |

326 |

6.27 |

|

Wells Fargo & Company |

1940 |

6.67 |

|

$ Total, % Weighted Average |

15367 |

6.00 |

Source: S. Pellerin (2024), Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

[6] As discussed below, the remedy is actually another symptom of the disease. Commercial banks directly hold about $1.7 trillion in Treasury securities, accounting for roughly 6% of the Treasury market and 7% of their own balance sheets. As Wenxin Du writes in the Financial Times (May 22, 2025): “The idea that lower total leverage requirements would encourage considerably more Treasury holdings from these commercial banks is questionable. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in 2023 after suffering losses on big holdings of Treasuries when interest rates rose highlighted the risks here. Prudent management would discourage banks from increasing long-term bond holdings funded by flighty deposits.”

[7] The literature on the 2020 crisis is large and features continued rear guard actions. We lack the space to survey it. The same holds for discussions of Fed bailout precedents and the extent to which those stretch traditional divisions between monetary and fiscal policies.

[8] Acharya and Laarits is another detailed analysis of the April turmoil that avows its results are consistent with an unwinding of basis trades, though the study does not focus on them. Interestingly, the minutes of the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee for April 30-May 1 include a comment in the staff review of the current economic situation that “the prevalence of the basis trade by hedge funds appeared to have declined from its peak but remained elevated by historical standards.”

[9] For example, page 27 of the Federal Reserve’s April 2025 Financial Stability Report asserts that “While hedge funds’ leverage rose to historical highs in the third quarter of 2024 and remained concentrated among the largest hedge funds, it likely decreased in early April as some hedge funds unwound leveraged positions amid heightened market volatility.” The study repeats the point on p. 33: “hedge funds’ leverage has likely decreased from historically high levels due to repositioning and unwinding levered trades in April.” And that “hedge fund repositioning and deleveraging may have contributed to the recent market volatility, both in equities and risky assets as well as in some longer-dated Treasury securities.” Of course, basis trades are only one type of leveraged trades.

[10] This point is technical and merits a longer discussion than we need here: “While funds appear to have partially exited these trades based on sales of the cheapest-to-deliver notes, it is not clear that these sales actually impaired Treasury market liquidity. Instead, the basis trade appears to have continued to provide net liquidity to underlying Treasuries relative to comparable off-the-run securities.” Its weight is also affected by how seriously one takes the comparison between March 2020 and April 2025, along with the actions of Fed in the former case and President Trump in the other.”

[11] When asked at a House Financial Services Committee hearing if the Federal Reserve will look into revisions to the supplementary leverage ratio, Powell replied: “Yes, I believe we will. I have, for a long time, like others, been somewhat concerned about the levels of liquidity in the Treasury market. The amount of Treasuries has grown much faster than the intermediation capacity has grown, and one obvious thing to do is to lower, is to reduce the effective [supplementary] leverage ratio, the bindingness of it. So that’s something I do expect we will return to and work on with our new colleagues at the other agencies, and get done.”

[12] A reader of a draft of this paper commented that “part of the point you are making here is the circular nature of much this activity…the Fed is saying there needs to be sufficient liquidity in the repo market, but that liquidity is collateralized by the same asset that the liquidity is being used to purchase.” Yes.

[13] Anticipating increases in governmental borrowing fueled by rising budget deficits, Scott Bessent, the Secretary of the Treasury, wants the money markets to smoothly absorb additional Treasuries. Hence, Bessent favors regulatory reform, stating (on April 9, 2025), “I previously raised concerns about whether the leverage capital restrictions are too frequently binding. The bank regulators are now hard at work to develop a proposal to ensure that leverage capital functions as appropriate.”

[14] Paritosh Bansal, “In the Market: How Harris, Trump promises could feed market’s addiction to the Fed,” Reuters, October 30, 2024.

[15] The financial sector also originates loans for consumption and for mortgages. Consumer credit by banks amounts to circa 16-19% of GDP during 2010-2024. Total household debt (which includes credit card debt, other consumer loans auto loans, student loans, and mortgages) stands at $18.2 trillion in the first quarter of 2025, or around 60% of GDP. Total intermediation by banks and non-bank financial institutions stands at around 170% of GDP. It must be borne in mind that the financial wizardry by banks and other financial firms is critically dependent on (real-economy) collateral including Treasuries, mortgage-backed securities, and asset-backed securities involving car loans, credit card debt etc. Banks are more than willing to originate credit to households in exchange for the underlying collateral that they can then use for their alchemical financial activities. Our conclusion remains unchanged, therefore: the colossal gross flows that sweep through the financial system are not at all necessary to support households and consumers.

[16] Wigglesworth’s article is based on a new report published by Barclays’ macro, credit and bank research analysts Jeffrey Meli, Bradley Rogoff, and Peter Troisi.