Thank you, Mr. Chairman, for inviting me here to testify today. I want to congratulate you and your Committee for trying to get to the bottom of why the banking crisis this country experienced was so severe. It is an honor to have a chance to help you in this work.

My testimony is built around the idea that financial markets closely resemble roads. These roads are used simultaneously by individuals and businesses. The purpose of building and maintaining financial roads is to allow ordinary citizens and corporations to create and divide wealth fairly and efficiently. Banking is regulated for the same reason that traffic is regulated: to coordinate potentially chaotic activity and to make all drivers behave more safely. But in banking supervision, norms that foster deception and abuse of the public trust have become imbedded in banks’ and regulators’ organizational cultures.

An organization’s culture has three components: (1) the entity’s professed missions and goals; (2) observable resources and procedures purportedly used to promote the goals; and (3) various unwritten norms that tell employees how they are supposed to behave in different circumstances if they want to have a successful career in that organization. Norms that conflict with the professed mission of the enterprise are drilled into insiders, but such norms cannot be directly observed or verified by outsiders.

Banking crises occur because bankers routinely abuse the financial rules of the road, knowing that supervisory norms are apt to exempt them from meaningful personal penalties. Incentives to exempt miscreants are at bottom a problem of inadequate professional ethics. If systems for supervising traffic flows were as distorted, as elitist, and as slow to respond as those for supervising banks in Europe and the US, ordinary citizens would be afraid to venture out of their homes.

The central problem is straightforward: safety nets encourage unhealthy relationships between banks and their regulators and distort the incentives of both groups in ways that harm ordinary citizens. In good times and in bad, regulatory and banking cultures encourage their country’s largest banks to take on too high a risk of ruin (i.e., too much tail risk). Existing financial accounting systems fail to identify and record the economic value that these incentives transfer from taxpayers to bankers and their stockholders.

I propose two straightforward and interlinked solutions. First, regulators must explicitly measure and manage the cost of safety net guarantees. Second, regulators should impose a series of graduated penalties on

individuals who violate important rules of the road. These two steps would help force TBTF banks to internalize the costs of safety net guarantees, and would negate the elitist norms that continue to corrupt the culture of regulation in the US and Europe.

Narrower Lessons from which these Solutions Arise

1. Safety nets can and often do cause financial fragility. Safety-net subsidies to under-supervised forms of risk taking by financial institutions create strong and enduring incentives for managers to search out proudly —and to exploit aggressively—legally permissible ways of putting institutional survival and taxpayer funds at risk.

To stop this, society needs to make subsidy extraction a source of disdain, rather than admiration. This will not happen until and unless regulators and supervisors strip out from reported profit flows the embedded value of the taxpayer credit support a TBTF bank receives. Much of this value comes from norm-based government delays in recognizing and resolving insolvencies. Extending accounting principles to highlight taxpayers’ stake can force regulators and auditors to focus specifically on whether and to what extent market extensions and financial innovations reduce the effectiveness of prudential policies.

Governments must not turn a blind eye either to regulatory capture or to the anti-egalitarian distributional effects and anger at government that bailouts engender. Although analysts agree that regulators should control systemic risk, most definitions of systemic risk leave out the role that regulators’ propensity to assist rather than to resolve insolvent institutions plays in generating it. A norm of helpfulness leads policymakers to act as cheerleaders for innovative forms of contracting and a norm of giving troubled banks the benefit of the doubt supports a proclivity for absorbing losses in crisis situations. The deference these norms elicit imbeds incentive conflict within the supervisory culture. To restore faith in the diligence, competence, and integrity of officials responsible for managing national safety nets, governments need to rework executive training programs and information systems, and to overcome unhealthy cultural norms that pervert the regulatory and financial sectors.

2. Fragility is rooted in conflicted incentives. Far from having purely altruistic motives, both in the private and the public sectors, managers have identifiable private interests. Because top government officials have to be reappointed by each new administration, they are effectively short-timers. This reinforces the norm of helpfulness by keeping them interested in ensuring opportunities for their own re-employment in future governments or through the “revolving door” into the sectors they regulate. In Ireland and elsewhere, this interest expresses itself in policies that tend to favor industry interests at the expense of ordinary citizens and, as a quid pro quo, enlist industry lobbying support for legislative initiatives that enhance an agency’s prestige, budget, and jurisdiction in the short run.

3. Dangerous incentive conflicts could be reduced if safety-net subsidies were measured conscientiously and compensation schemes paid managers and taxpayers in better ways. Although officials claim otherwise, it is no accident that they repeatedly fail to foresee the emergence of crisis pressures and respond to them in an elitist fashion.

4. These conflicts lead to regulatory capture, and regulatory capture expands implicit and explicit government guarantees that become part of the equity funding structure of too-big-to-fail (TBTF) banking organizations. Contingent taxpayer support deserves to be recognized as an equity claim both in company law and in financial accounting. The rest of my statement develops this important point.

Financial safety nets coerce taxpayers into becoming disadvantaged suppliers of loss-absorbing equity funding. To provide legal protections parallel to those that explicit shareholders enjoy, legislation is needed to establish two things: to clarify that managers of TBTF firms owe enforceable fiduciary duties of loyalty, competence, and care to taxpayers and to criminalize aggressive and willful efforts to transfer value from taxpayers to shareholders and managers.

Characterizing bailout support as owners’ equity leads us to look at taxpayer positions in TBTF institutions as a portfolio of trust funds. This way of thinking casts regulators as trustees and opens up the possibility of installing carefully recruited teams of private parties to serve as co-trustees. The formal establishment of such trusteeships would lead officials to judge regulatory performance in terms of its effects on the value of taxpayer equity positions and exposures to ruin. It would also require regulators and protected institutions to re-work their norms, information systems, and incentive frameworks to support this effort.

5. Incentive conflicts lead TBTF firms’ creditors and internal and external supervisors to short-cut and outsource due diligence. I believe that G-20 and Basel III strategies of reform do not adequately acknowledge these conflicts or the patterns of “deferential regulation” they sustain. To lessen these conflicts, governments need to rethink the informational obligations that insured financial institutions and their regulators owe to taxpayers as de facto equity investors and to change the way that information on industry balance sheets and risk exposures is reported, verified, and used by supervisors. Without reforms in the practical duties imposed on industry and government officials and in the way these duties are enforced, financial safety nets will continue to expand and their expansion will undermine financial stability.

6. TBTF guarantees are more than a form of bond insurance on outstanding debt. The coverage of TBTF guarantees are richer than insurance on outstanding debt because, as long as regulators forbear from resolving its insolvency, a truly TBTF firm can extract further guarantees by issuing endless amounts of additional debt in both domestic and foreign markets.

7. Every guarantee contract has two components. The first allows the guaranteed party to put responsibility for covering losses that exceed the value of the assets of the banking company to the guarantor. The guarantor is conceived as writing the put. But the put is not the whole contract. No guarantor wants voluntarily to expose itself to unlimited losses on a put option.

For this reason, all guarantee contracts incorporate a stop-loss provision that gives the guarantor a call on the assets of the firm. Ordinarily, the stop-loss kicks in just as insolvency is approached or breached. The risk exposure a guarantor assumes from simultaneously writing a put and holding a call is the economic equivalent of an explicit equity position.

Efforts to exercise the government’s call are termed prompt corrective action. In the US and Europe, we did not see much prompt

corrective action for TBTF institutions during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-9. The policy actions we did see have helped the world’s TBTF banks to become bigger and more politically powerful than ever before.

Why and How Safety-Net Guarantees Lower and Distort the Funding Cost of TBTF Firms

In good times and in bad, being too big to fail simultaneously lowers both the cost of a firm’s debt and the cost of its equity. This is because too-big-to-fail guarantees lower the risk that flows through to owners of both classes of securities. Guarantees chop off bondholders’ and stockholders’ losses at a specified point and direct the flow of further losses to taxpayers.

When regulatory norms of helpfulness and mercy prevent the government’s call on assets from being exercised, guarantees shift exposure to ruinous losses away from creditors and stockholders. It is as if TBTF banks’ profit flow moves through a pipeline with a Y junction in it. Insolvency exists when an institution is unable to cover its debts from its own resources. When a TBTF firm such as Anglo-Irish Bank becomes effectively insolvent, a political switch is thrown that channels further losses to taxpayers until and unless the firm manages to recover its solvency again.

Deeply insolvent banks are zombie institutions. They can only operate because they are backed by the black magic of government implicit guarantees. The most important part of zombification is a passive policy of norm-based regulatory forbearance, which allows institutions that are insolvent to continue to roll over — and even to expand— their debt.

By definition, the government’s right to take over a firm’s assets will never be exercised in a financial institution that is truly too big to fail. Nonexercise means that the government has effectively ceded the value of its loss-stopping rights back to the too-big-to-fail stockholders. The value that forbearance gives away becomes taxpayers’ responsibility.

In the US, the AIG case has much in common with that of Anglo here. My written statement includes a graph, Figure 1, that portrays the behavior of AIG’s stock prices before, during and after the 2008 crisis. The only time AIG’s stock price approached zero –and it did so twice—was when the possibility of a US government takeover fell under active discussion, so that the probability of stockholders’ continued rescue was falling. As soon as this course of action was tabled, the stock price surged again because TBTF policies handed the value of the stop-loss back to AIG’s stockholders. I am sure that the stock prices of a zombie bank such as Anglo in Ireland exhibited similar patterns prior to its nationalization.

The problem of supervisory forbearance is intensified by the ongoing government-subsidized consolidation of the banking business into the hands of the world’s biggest banking organizations. In Ireland, banking appears well on its way to becoming a duopoly with a growing and fearsome ability to pervert and abuse the rules of your financial roads.

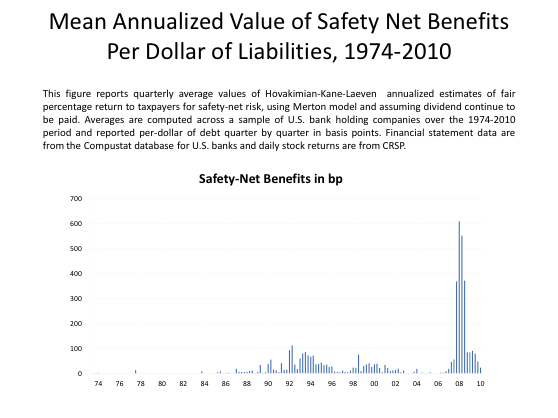

Figure 2 presents estimates that Armen Hovakimian, Luc Laeven and I prepared to track in basis points the value of the average quarterly dividend that US taxpayers ought to have been paid by large banking firms during 1974-2010. The value of this dividend shows a cyclical pattern. But by looking across the cycles, we can also discern the effects of cumulative learning about how to benefit from safety-net guarantees and growing exploitation of the value of these guarantees by large-bank managers. With each successive recession, more benefit is extracted by too-big-to-fail institutions. These patterns ought to be observable in the Irish scene as well. I fear that far greater and more-dangerous subsidy flows will reveal themselves in the next crisis.

How to Think About Guarantees

I want you to think of implicit government guarantees not as a cure, but as a source of instability. It is important for this committee to understand the difference between guarantees, insurance, and loan contracts and the differences in the ethical duties each imposes on the contract’s counterparties. I warn your Committee not to fall into the trap of thinking of bailout expenditures as either loans or insurance payments.

An insurance company does not double and redouble the coverage of drivers that have revealed themselves to act as recklessly as TBTF firms did during the last economic boom.

Similarly, lifelines provided to an underwater firm cannot be thought of as low-interest loans. Loans are simply not available to firms that are in zombie condition.

Something must be done to sanction the reckless pursuit of subsidies at TBTF enterprises. Exhortations are not enough. The type of sanctions I would propose are outlined in the last part of my statement. The key point is for society to recognize that the deliberate exploitation of too-big-to-fail guarantees is a form of criminal theft and develop ways to punish not only individuals who engage in it directly, but also any higher corporate officials who can be shown to have encouraged it.

Need for Individual and Not Just Corporate Sanctions

I believe the way we frame problems is critically important in policy making. In the future, legal systems must make it crystal clear that recklessly increasing a bank’s risk of ruin is a form of theft from what I have framed as a taxpayer trust fund. Rules of the financial game must acknowledge that it is wrong for individual managers to adopt risk-management strategies that willfully conceal and abuse taxpayers’ equity stake. These behaviors deserve to be sanctioned explicitly by both corporate and criminal law and not excused by insurance law as inevitable moral hazard.

I have stressed that, as the net value of two options, the risks incurred in backstopping TBTF firms cannot be calculated and priced as a straightforward product of loss intensity and loss probability as loss exposures on bond or insurance contracts can. I have sought to convince you to recognize bailout support as loss-absorbing equity funding provided to a zombie firm at a time when no rational investor will advance it a nickel.

In my view, aided and abetted by deferential regulators, US, Irish, and other European bankers have committed crimes on the public that deserve to be characterized as theft by safety net. The victims are current and future citizens. The people who commit this crime are individual managers and supervisors. In recklessly risking their firms’ survival to gain subsidies from shifting tail risks to taxpayers, managers impose needless costs and dangers on other users of financial roadways.

Banking supervisors have let society down in two ways: (1) by not setting up the equivalent of radar systems and helicopter surveillance to track excessive speed and aggressive driving and (2) by not developing a penalty structure that punishes unruly behavior in a meaningful and timely fashion. Effective regulation and supervision must establish disincentives that can dissuade banks that are tempted to drive at perilous speeds or to undertake dangerous maneuvers. To improve driving habits more than marginally and temporarily, miscreants must be identified and risk shifting must be rendered personally unprofitable for them.

The analogy between regulating banks and regulating vehicular traffic suggests that, country by country, the penalty structure and burdens of proof in cases of safety-net theft could be designed to parallel those used in traffic courts. In the US, we already have administrative procedures for enforcing regulatory findings whose jurisdictions resemble those of traffic courts. Most states combine: (1) fines for minor violations, (2) a point system which hikes the penalty for repeated or more-serious violations, and (3) procedures for transferring particularly consequential cases (such as vehicular homicide or extreme drunken driving) to ordinary criminal and civil courts.

No matter what regulators finally do with their traditional tools such as capital and liquidity requirements, if they do not set up sanctions that punish individuals for acts of willful or complicit safety-net theft, we are bound to get more wrong-doing in the future.

Between 2008 and late 2013, fines levied for bad behavior on the ten largest US and European banking firms amount to roughly 157 billion pounds sterling (Bryant and McCormick, 2014). I believe that genuine reform would require authorities to prosecute publicly

individuals in banking organizations whenever they have compelling evidence of costly forms of common-law fraud. I believe there is substantial value in documenting egregious violations and prosecuting violators in open court. Settling violations of banking law by large fines negotiated out of court shames the firm, but tends to conceal embarrassing details of regulatory and ethical failure and reckless risk-taking whose revelation promises to deter other individuals from engaging in similar behaviors in the future. The public needs to understand how much miscreant managers benefit when the burdens of the corporate fines and admissions of guilt they do or do not negotiate serve principally to punish shareholders instead of naming and sanctioning individual managers.

References

Bryant, Hugh D., and Roger McCormick, 2014. “The Conduct Costs Project-Description and Suggested Prescription,” Posted on CCP Research Foundation Website (July 21).

Gurgiev, Constantin, Charles Larkin, and Brian Lucey, 2014. “Learning from the Irish Experience – A Clinical Case Study in Banking Failure,” Comparative Economic Studies (forthcoming).

Leach, James A., 2011. “The Lure of Leveraging: Wall Street, Congress and the Invisible Government,” in Tatom, John (ed.), 2011. Financial Market Regulation. New York, Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 187-220.

Morgenson, Gretchen, 2014. “Fresh Doubts over the Bailout of A.I.G.,”

New York Times (Dec. 20).

Figure 1

AIG Stock Never Became Valueless

Figure 2

* I wish to thank Robert Dickler, Stephen Kane, Brian Lucey, and Frank Partnoy for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this testimony. The extra line in the title “Thinking About Banking Crises” has been added by the INET editors for clarity.

Leinster House, Dublin, Ireland

Speaking Version Used at Hearing, January 28, 2015