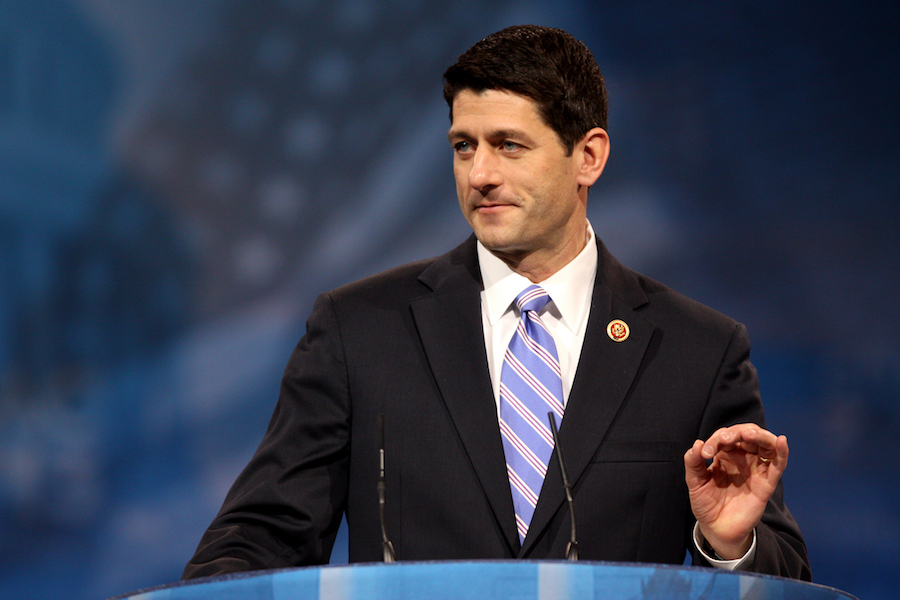

From the lips of Paul Ryan, Chief Spokesman of Blame-the-Poor politics, came a curious mea culpa just last week. Oops! He should not have referred to hard-working Americans trying to feed their families as “takers” (Mitt Romney gained attention for similar remarks in 2012, but his running mate Ryan had already been on the makers/takers theme for years). Ryan further admitted that when it comes to economic distress, he didn’t really know what he was talking about.

“There was a time when I would talk about a difference between ‘makers’ and ‘takers’ in our country, referring to people who accepted government benefits,” said the speaker. “But as I spent more time listening, and really learning the root causes of poverty, I realized I was wrong.”

Well, yes. But a question: If the takers aren’t standing in the unemployment line or rushing home from the second job to change diapers, then just where are they? Because an awful lot of America’s resources have gone missing. Like money that should be going to education, job training, healing the sick, retirement funds, infrastructure, and, you know — life.

Ryan didn’t quite get to that part. As he and the rest of the country’s pundits and politicians puzzle over this crazy political season, they might do well to get themselves a copy of Rana Foroohar’s forthcoming book, Makers and Takers: The Rise of American Finance and the Fall of American Business (to be released on May 17). The title was inspired by Ryan’s very own (now-disowned) rhetoric, the favorite shorthand for trickle-down myths that paint the rich as the creators of jobs and innovative products and the rest of the population as lazy good-for-nothings.

That line worked pretty well before the financial crisis. Now, not so much.

Foroohar, TIME assistant managing editor and economic columnist and global economic correspondent at CNN, has a pretty good idea where to find the takers. They are neither single moms in inner city housing projects nor unemployed white men in Appalachia.

They are the denizens of plush Wall Street offices, and they have pretty much absconded with the American Dream. Despite the remarkable ability of financiers to hide behind complexity and dodge the spotlight of the media, the regulators, and the law, Americans are copping onto the breadth and depth of the swindle. They have just about had it — which is why voters have been flocking in droves to the fiery Bernie Sanders, who wants to jail financial crooks and end to Too Big to Fail, and to Wall Street heckler Donald Trump, who describes hedge fund managers as worthless moneymen who ” get away with murder” and gleefully trashes uber-bankers like Jamie Dimon.

Foroohar has traced a seismic shift that has not only left Washington kissing the feet of Wall Street, but has turned previously normal and comprehensible activities, like making stuff and selling it, into insanely complicated financial death races where ordinary Americans are the road kill. This very shift has turned companies like Apple from makers of cool gadgets to a market-rigging megabanks, pharmaceutical companies into cold-blooded financial predators, and the American Dream of dignity, health, and the pursuit of happiness into a fantasy for large swaths of the population.

For Foroohar, “takers” is how you refer to people who do nothing of value for society and whose activities leave students crushed with debt, retirees living in RVs, capable workers struggling to land a third-rate gig, and sick people so many tasty morsels for financial vultures.

Through in-depth reporting, historical analysis, and consultation with a range of forward-thinking economic minds, including Institute chair Adair Turner, president Rob Johnson, and grantees like Joseph Stiglitz and William Lazonick, her book explains how our financial system stopped funding new ideas and projects and started extracting precious resources from Main Street. Her writing leaves a vivid impression that once the financial wizards get their way, nobody in safe — from the young college grad next door drowning in debt owed to predatory lenders to the child halfway around the world whose dinner fell victim to commodities speculation.

As I turned the pages, I began to imagine Big Finance as a giant exotic vine from some florid catastrophe movie that has grown out of control, creeping onto the roofs of our houses, reaching into the food on our plates, tightening its hold on our wallets — and even taking over our minds. I’m embarrassed to say how many times I hear phrases like “human capital” and “return on investment” issuing from my own lips — finance-originated concepts used to describe relationships and activities that have little to do with spreadsheets.

Foroohar follows the financial Cheshire Cat as he baffles and jumps through tax loopholes, spins through revolving doors, and sneakily gobbles up savings accounts. She shows how the trend of financialization — an ugly word for the ballooning of the financial sector relative to the overall economy — has led directly to the things that have Americans feeling so betrayed, like crappy McJobs, foreclosed futures, rampant volatility and insecurity, a stalled economy, and an increasingly painful gap between the rich and everyone else. Which is why things like the decline of the middle class and economic inequality have become front and center issues in the 2016 presidential campaign, no matter how much elites of both parties would prefer to change the subject.

As Foroohar warns, it matters who is president and whom that president listens to. It was Reagan’s advisors who brought America deregulatory fever and the rise of stock buybacks (once considered unlawful market manipulation in America), while Bill Clinton’s team later opened the floodgates of speculation with the repeal of Glass-Steagall. These presidencies were marked by people whose mindsets favored markets over the real economy. That had better not go on, because if it does, the angry season of 2016 may be the dress rehearsal for something much nastier four years down the road.

The good news is that the giant imbalance of power between finance and the real economy can be fixed, and we know a lot about how to do it. The bad news is that as long as the financiers have the power, they will do everything in their power to stop sensible and entirely doable reforms.