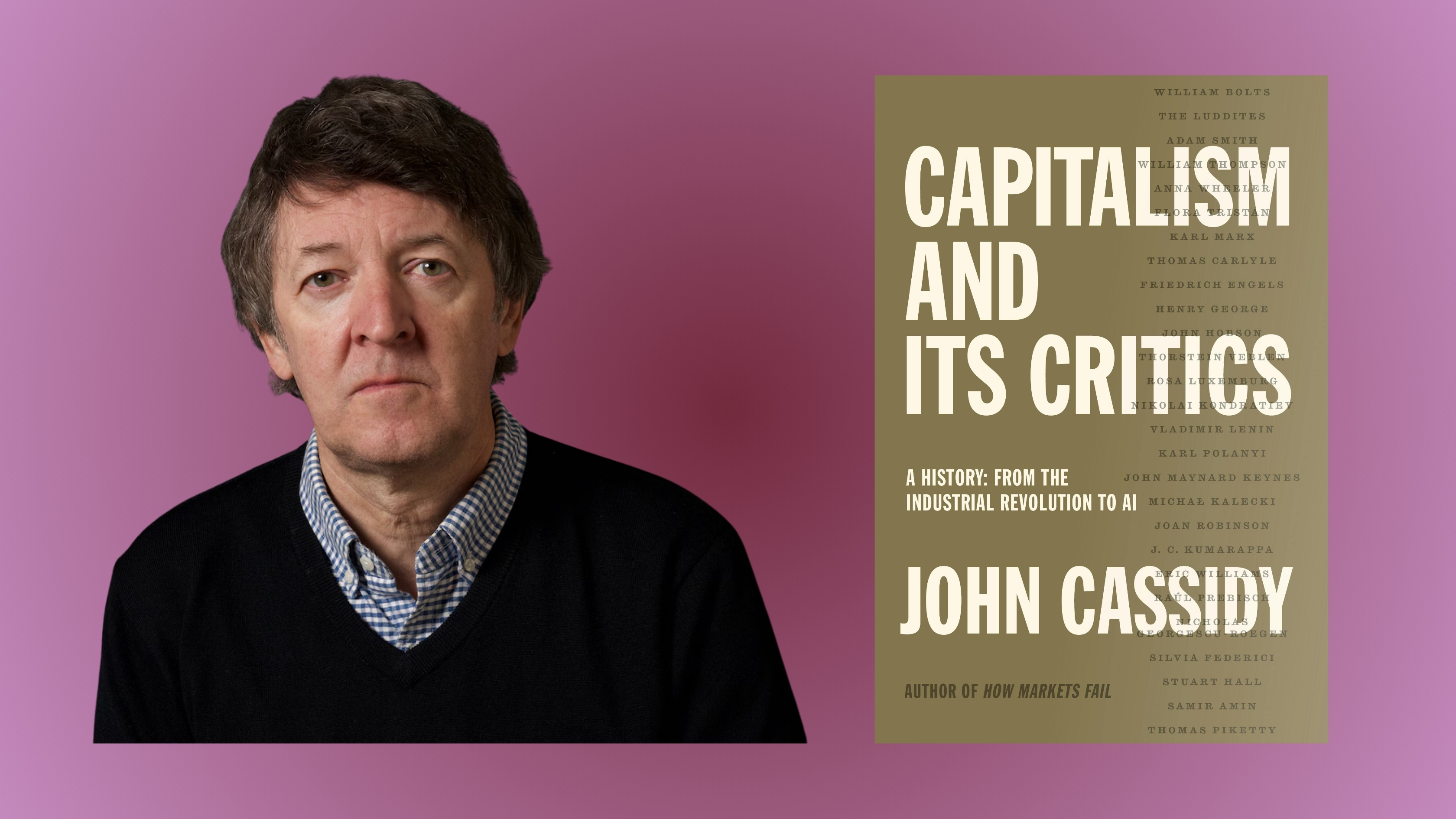

In Capitalism and Its Critics, New Yorker writer John Cassidy brings to life the figures who warned of monopoly power, inequality, environmental peril, and authoritarianism—forces still at work today. He discusses his book with Lynn Parramore.

As capitalism confronts rising challenges—from authoritarianism to life-changing technology—New Yorker writer John Cassidy’s Capitalism and Its Critics: A History from the Industrial Revolution to AI offers a timely exploration of the thinkers who have challenged the system for centuries.

From 17th-century monopolists to today’s tech giants and AI upheavals, Cassidy traces a long tradition of voices warning about inequality, unchecked power, and the erosion of democracy. The questions haunting our moment—about elites, monopolies, globalization, and rising authoritarianism—aren’t new, but they feel more urgent than ever.

His book draws on a broad range of voices—from icons like Smith, Marx, and Polanyi to overlooked figures such as William Thompson and Flora Tristan (grandmother of painter Paul Gauguin), along with key modern critics like Joan Robinson, Michał Kalecki, and Paul Sweezy. Across centuries, their warnings echo: capitalism promises progress, but it often brings instability, inequality, and unrest.

In the following conversation with the Institute for New Economic Thinking, Cassidy unpacks how capitalism shapes more than just economies—it reshapes our politics, values, and sense of humanity. His book raises a pressing question: Can we reform the system before it chews up the democratic ideals it once helped build?

Lynn Parramore: You’ve pointed to Bernie Sanders’ 2016 run for president as an event that sparked the idea for your book. What about that political moment got your attention?

John Cassidy: I think people forget now what a momentous time that was. You had Bernie running from the left with a critique of capitalism and globalization. At the same time, you had Trump running from the right with an economic nationalist critique. I’ve been reporting on the U.S. for forty years, and I couldn’t remember another moment when critiques of the system were coming so strongly from both the left and the right.

What’s also notable about 2016 is that most political pundits initially wrote off both Bernie and Trump. And yet Bernie nearly won the Democratic nomination—before the party united against him—and Trump steamrolled the Republicans. It struck me that this was really a crisis of legitimacy for the system, and I thought, “There’s a book to be written here—something to explain how we got to this point.”

Initially, I imagined it would cover a much shorter time frame—maybe going back to the post-Cold War rise of neoliberalism. But then I realized there were already dozens of books written on that subject—some very good, others not so much—and I wasn’t sure what I could add. I also realized that many of the problems and debates surrounding so-called late capitalism, or what I refer to as “hypercapitalism,” go back much further than the 1980s.

So I kept moving backward. At one point, I thought maybe I’d start in the 1940s with the rise of the Keynesian social-democratic state. But then I had to explain how that came about, which meant going back to the Great Depression—and so on. Eventually, I thought, “To hell with it. Why not go all the way back and do the whole thing from start to finish?”

That led me to ask: where do I begin? There’s a long-running debate among economic historians about when modern capitalism actually starts, but I decided to pick around 1770, which marked the approximate start of the Industrial Revolution. It was also a moment when British mercantile capitalism, the precursor to industrial capitalism, was in crisis, with the mighty East India Company on the verge of bankruptcy. The date is a bit arbitrary, but it gave me a starting point. Then I realized I was writing a history of the last 250 years.

LP: How did you hit upon the idea of telling the story through the biographies of individual critics?

JC: For one, there are already many histories of capitalism. But more importantly, I’m interested in critiques of capitalism, and the people behind them are fascinating. Telling the story through them helps bring in readers and humanizes the ideas.

I’d read Bob Heilbroner’s The Worldly Philosophers decades ago, and I even had lunch with him when I first came to New York—he was at the New School at the time. I always admired that book, which focused on great thinkers. I wanted to do something broader—bring in both well-known and lesser-known figures, and make it global rather than just Anglo-centric.

LP: How do you view Trump’s second victory in light of the disillusionment with capitalism bubbling up in 2016?

JC: That’s a great question. In one sense, I think Trump talked and acted himself out of office the first time—just so much chaos and erratic behavior. A lot of his non-core supporters grew tired of that. Telling people to drink bleach during a pandemic isn’t exactly a vote-maximizing strategy.

So, he alienated enough people to lose to a generic Democrat like Biden. But the underlying forces that led to his rise in 2016—the system’s crisis of legitimacy—hadn’t gone away, either. The left-wing critique—led by Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren—remained powerful. And Trump’s brand of economic nationalism had also stuck around. In fact, it had spread to Europe and beyond. So, strictly in terms of the book, I don’t think his re-election changed much of the underlying story. Of course, the actual presidency has been different. The chaos is even more chaotic than before, and the authoritarian aspect is even scarier.

LP: What would you say to someone who might view Trump’s second win as a renewed embrace of capitalism? After all, we have a businessman in the White House again, and capitalists like Elon Musk wield great influence.

JC:. I wouldn’t see it that way. Sure, Elon Musk was in the administration, but his recent departure highlighted the schism between the corporate and populist sides of Trumpism. The main reason Trump won the election, in my view, was inflation. It didn’t only bring down Biden—it hurt Rishi Sunak in the UK, damaged Merkel’s center-right party in Germany, and also impacted centrist parties in France. So I think what we’ve seen was more about disillusionment with the political establishment than any kind of renewed faith in capitalism.

LP: When you look back to the 18th century, long before Marx or Keynes, what issues were early critics raising that still seem familiar or unresolved today?

JC: There are lots of them. As I said, I start the book with mercantile capitalism—or colonial capitalism, you could call it. It was based not only on colonial exploitation but also on state-sanctioned monopolies. My first critic is William Bolts, a whistleblower from the East India Company, which was given a monopoly of trade east of the Cape of Good Hope—essentially all of Asia—by Queen Elizabeth I in 1600. It had developed into a multinational corporation, rivaled only by the Dutch East India Company.

These were trading corporations whose primary goal was to enrich their employees and shareholders. In India, the British East India Company used its monopoly power to underpay local producers—in modern terms, it had monopsony power. And then, when it transported the goods—things like cotton, tea, and spices—back to Britain, it also benefited from being the sole importer.

It’s not widely recognized, but Adam Smith himself was a fierce critic of this kind of monopoly capitalism. When he wrote The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, it was intended as a critique of mercantile capitalism. People think of Smith as a defender of capitalism, but in my book, he appears as a critic—especially of monopolies. He has famous passages criticizing individual businessmen, saying that if more than two or three gather for more than ten minutes, the conversation inevitably turns to raising prices and exploiting consumers.

So, Smith wasn’t defending capitalism per se; he was defending competition. He detested monopolies like the East India Company and strongly criticized them in The Wealth of Nations.

Today, of course, we live in a world where monopoly capitalism has returned—if it ever left. You see it in the tech industry most strikingly, but also in other parts of the economy. For example, look at the private equity roll-ups of what used to be competitive industries—even small businesses like veterinary and doctors’ offices.

Beginning with Smith, many critics of capitalism have focused on monopoly power. In the book, I write about John Hobson, the British left-liberal; Rosa Luxemburg, the Polish-German revolutionary; and Vladimir Lenin. They were all critics of monopoly capitalism, which, in their view, combined monopolies and imperialism. More recently, the left-Keynesian Joan Robinson as well. Basically, almost every major critic—left or right—has flagged this aspect of capitalism, and I think most non-economists agree with them. In Silicon Valley, monopolies are sometimes seen as a “just reward” for innovation, but most people view them as harmful.

Another theme that runs through the book is globalization. People think it’s new, but mercantile capitalism was also a global system. The East India Company was a global multinational headquartered in London, issuing orders to workers in Indonesia and India. The transatlantic slave trade, which was a major feature of colonial capitalism, connected three continents. I quote the historian Joyce Appleby, who said the tropical plantations were essentially “factories in the fields.” They represented mass production—relative to their time—with hundreds of enslaved people producing goods for export.

LP: You mention that in 1829, Thomas Carlyle described his era as the “Mechanical Age,” referencing how industrial routines and mechanical thinking were reshaping life. If you had to name the age we’re in now, what would you call it? What drives its logic?

JC: Well, this is not very original, but I think you’d have to say it’s turning into the Age of Data and AI. There’s a lot of hype around AI, of course, and the companies behind it have a vested interest in saying it’ll change everything. But even skeptical economists acknowledge that we’re entering a new industrial revolution—the third, fourth, or fifth, depending on how you count.

Of course, it’s already really the Age of the Microchip, which began in the 1980s. But now we’re in a second phase where computational power has become so immense that it’s enabling this data and AI revolution. The major breakthrough isn’t intellectual—the neural networks that underpin the new AI models aren’t particularly new—it’s brute-force computing and the availability of huge amounts of data. Taken together, these factors are transformative, maybe comparable to steam power or electrification.

Another of my subjects, Nikolai Kondratiev, an early twentieth-century Russian economist who was eventually killed by Stalin, argued that capitalism evolved in “long waves” driven by technological innovation and investment. Right now, it feels like we’re entering a new Kondratiev wave—whether for good or ill, we’ll see.

LP: Carlyle talked about how mechanization associated with capitalism significantly changed human life. Do you think this data/AI revolution is reshaping human existence profoundly?

JC: Yes, I think that’s a very important point. Most of my book is focused on economics and policy. But early critics like Carlyle—and of course Marx, in his writings on alienation—have always argued that capitalism affects our humanity. Even before Carlyle, the so-called utopian socialists, whom I also write about, emphasized the dehumanizing aspects of industrialization and the factory system.

Previously, most workers had labored in small workshops or at home. Now, in cities like Manchester, they were forced into these “dark, Satanic mills,” to use Blake’s famous phrase. Conditions were oppressive—long hours, child labor, strict oversight. Even conservatives like Carlyle found it inhumane.

Fast forward 200 years, and there are some obvious parallels. For example, technology-enabled “surveillance capitalism” gives employers the power to monitor workers 24/7. Think of truck drivers with GPS in their cabs—they can’t even take a break without being tracked. AI expands those possibilities. We don’t yet have a full understanding of how it will affect human behavior, but if we reach a stage where machines are truly smarter than us—and they’re controlled by profit-seeking corporations—that’s a world-shattering development.

LP: In the sense that it demotes us?

JC: Exactly. And I don’t want to sound like an alarmist, but an AI-driven economy seems to be an increasingly realistic prospect. Even some academic economists are sounding the alarm. A few years ago, they were generally optimistic, I’d say. They viewed AI as another productive tool—something that would boost productivity and wages, albeit with some disruption during the transition.

But earlier this year, when I was working on a piece for The New Yorker, I found that the mood had changed, and some prominent economists were focusing on a darker scenario in which AI becomes a substitute rather than a complement to human labor. That implies massive job displacement, which, again, echoes the early industrial revolution. Of course, many economists still argue that the lost jobs will eventually be replaced by new ones—we just don’t know what those jobs are yet. Maybe they’re right. We’ll know in 10 or 20 years. But even if you take the optimistic view, it seems like there’s still going to be a huge disruption.

LP: Economist William Lazonick and others critical of unfettered capitalism warn against assuming massive job losses from tech breakthroughs are inevitable—both because history shows otherwise and because that argument has been used to discipline labor.

JC: I think that’s right. If you look at history, the Industrial Revolution eliminated a lot of artisanal jobs, but it also created massive numbers of factory jobs. More recently, automation and globalization have eliminated many factory jobs, but the service economy has expanded greatly. Today, roughly 80% of our economy is service-based.

But you can also turn that argument around. If AI is primarily targeting the service sector—which seems to be true—then it’s striking at the heart of the post-industrial economy.

LP: You have a chapter focusing on Austro-Hungarian economist Karl Polanyi, whose analysis of authoritarianism’s rise in Austria included the belief that unchecked capitalism inevitably leads to either socialism or fascism. Is that idea relevant today?

JC: When I write about the interwar era, I focus a lot on Keynes and Polanyi. I came out of the British Keynesian tradition, which—oversimplifying a bit—held that if you maintained aggregate demand, full employment, and a strong social safety net, capitalism would function pretty well. Add in regulation of the financial sector, as was the case in the Bretton Woods system, and you had a stable framework. And that approach did work very well for about 30 years after 1945.

Polanyi, as you mentioned, had a darker view of things. He came out of the socialist experiment in 1920s Vienna—“Red Vienna”—which provided its residents with things like social housing, education, and healthcare. It was municipal socialism in action, and it attracted progressives from around the world. But in the early 1930s, fascism came to power in Germany and quickly spread to Austria. Polanyi, who was Jewish, fled Austria; some of his family did not escape and perished in the Holocaust. That tragic history deeply shaped his worldview.

In the 1930s, Polanyi published a series of essays arguing that capitalism and democracy were ultimately incompatible. He believed capitalism created internal contradictions and tensions that would eventually destroy liberal democratic systems, leaving only fascism or socialism as viable alternatives. When I was first studying economics 40 years ago, that vision had largely faded. It was widely assumed that capitalism and democracy could coexist—with some tensions, but fundamentally they were compatible. However, with the recent rise of right-wing authoritarianism and capitalism, Polanyi’s skeptical arguments have become much more salient.

Later in life, Polanyi became a bit more optimistic. He admired the New Deal and Roosevelt, and he initially supported the postwar Labour government in Britain, which founded the welfare state and nationalized some large companies. But the onset of the Cold War made Polanyi more pessimistic again; he viewed it as another form of authoritarianism.

So while Keynes was the dominant mid-century thinker, I think Polanyi deserves to be recognized alongside him. Keynesianism—particularly American Keynesianism—didn’t grapple much with political economy, and that’s a major omission. In the 1940s, two more of my subjects—the Polish economist Michał Kalecki and the American Marxist Paul Sweezy—criticized the original Keynesian vision for this reason. What the last few decades have taught us is that political economy is central—you can’t ignore it when you’re talking about economics. I think that’s why Polanyi is experiencing a revival as a major figure.

LP: It sounds like you’ve evolved into a sort of Keynesian/Polanyian hybrid.

JC: Up to a point. But I should note that some of the original British left-Keynesians thought deeper structural reforms were necessary. Joan Robinson, for example, supported a mixed economy that included nationalized industries and extensive government efforts to stimulate investment. Kalecki argued that the business community—the capitalists—would not support full employment over the long term because it would undermine their control of the workplace.

Over the past few decades, I’ve come to appreciate those critiques. So these days, I sometimes call myself an “old Keynesian.” I’ve never considered myself a “New Keynesian.”

LP: One figure who intrigued me in your book was the Irish economist William Thompson. While he’s likely unfamiliar to many readers, his insights into capitalism, put forth in the early 19th century, feel remarkably prescient. He warned about extreme wealth inequality and its ability to empower unqualified elites. What can we learn from that?

JC: Yes, Thompson is fascinating. Maybe I was drawn to him because of my Irish roots—both sides of my family came from Ireland, and my maternal grandmother was born in Cork, which is where Thompson lived. But he is also a major thinker who was writing about capitalism and inequality decades before Marx and Engels. He was a member of the Protestant gentry.

As a young man, he managed to crash the family business, and thereafter he lived as a landlord—a pretty benevolent one by all accounts. He spent most of his time writing, reading, and engaging in public debates. He was a friend of Jeremy Bentham, the utilitarian philosopher, with whom he stayed in London.

In the 1820s, Thompson argued that inequality is inefficient. Using a utilitarian logic, he highlighted the diminishing marginal utility of wealth—the idea that extra income adds less and less to well-being the richer you are. That idea, taken seriously, justifies a more equal income distribution. He made this case clearly and rigorously, even without formal mathematics.

Thompson also coined the term “surplus value” and criticized the exploitation of labor. In practical terms, he was deeply involved in the cooperative movement, which proposed small, self-sufficient communities as an alternative to industrial capitalism. These proposed communities faced major challenges, and Thompson never could raise enough money to launch one of his own, but you can see echoes of them today in the degrowth movement and renewed interest in localism and sustainability.

LP: Capitalism spent the last century shifting between Keynesianism and neoliberalism. Where do you think it’s heading now?

My book is primarily a history, not a prediction. But at the end of it, I do speculate a bit about where things may be heading.

One option on the table is the Chinese model—a hybrid of state socialism and capitalism that I call state capitalism. After witnessing the failures of shock therapy in Russia, China kept its state enterprises intact and layered a capitalist system on top of them. It’s been enormously successful economically, lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty and making great advances in technological terms. I don’t think Western democracies will adopt this model, but it’s a powerful example for the Global South.

On the right, there’s the rise of economic nationalism—Trumpism, basically. High tariffs, impermeable borders, crony capitalism. This resembles Mussolini’s 1920s model in some ways. Despite its economic incoherence, it has a strong political appeal. We see versions of it across Europe: Farage in Britain, the AfD in Germany, Le Pen in France.

In the center, you still have remnants of neoliberalism, but it’s weaker politically. On the left, traditional state socialism is largely discredited. However, anti-capitalist degrowth is gaining some traction, particularly among young people concerned with climate change and consumerism.

What’s the center-left offer? In my last chapter, I highlighted some of its elements. As in the original Keynesian vision, full employment is central. Since the Fed began targeting lower unemployment about ten years ago, wages at the bottom have risen for the first time in decades. But with weakened labor unions, other labor market mechanisms could also be employed to strengthen labor—things like wage boards in particular industries and regional minimum wages linked to the local cost of living. Then there is vigorous anti-trust to tackle monopolies, international cooperation to tackle tax evasion, and maybe a global wealth tax, which could well become essential if AI leads to another big shift in income from labor to capital that further denudes the tax base. And, of course, more effective action to tackle climate change.

So intellectually, I think some of the framework for a new social bargain already exists. The biggest challenge is political: how do you build a coalition to support it in a time where much of the old working class has moved to the right, drawn by nationalist demagoguery? That’s a huge task.

LP: Several of the critics you explore—and you alluded to this earlier—see capitalism’s problems as going beyond just policy. They identify a values issue, arguing that capitalist systems tend to promote dehumanizing values. Keynes, for example, expressed a hope that capitalism would move past capitalist values. I’m curious how you see the reforms you mentioned in light of that kind of critique.

JC: That’s always been the challenge. If you’re a center-left person, you’re often accused—particularly by the far left—of being an apologist for capitalism. In some ways, they’re right: you are trying to reform and preserve the system while also making it more humane and equitable.

Recently, I did an event with Jared Bernstein, one of Biden’s economic advisors, and he offered a great typology for understanding the critics I discuss in my book. He said there are two kinds: critics of baseball and critics of zoos. Critics of baseball love the game but think it’s gone off track—they want to reform it. Maybe the strike zone is too big, there’s too much money involved, the games take too long. But they still love baseball and want to make it better. Then there are the critics of zoos—people who believe zoos are fundamentally immoral. They don’t think zoos should exist at all because it’s wrong to lock up wild animals.

As Bernstein said, my book includes both kinds of critics. Take someone like Rosa Luxemburg: she was a zoo critic. She believed capitalism was fundamentally immoral and exploitative, and that it should be overthrown. During the Spartacist uprising in Germany after World War One, she gave her life for that belief. She was murdered by members of a right-wing militia.

Then you have the baseball critics—like Keynes. He saw capitalism as a necessary evil. He believed it was based on pathological, money-grubbing values, but he also believed it delivered material progress in a way no other system could match. That’s always been the strongest argument for capitalism: over the long term, it raises living standards. In a famous essay published in 1930, he said that, because of productivity growth, by 2030 people’s wages would have increased dramatically and their basic needs would be met. In that world, he imagined, capitalist values would fade. People would only work a few hours a day and spend the rest of their time on more enriching pursuits—going to the opera, reading philosophy, tending a garden, playing sports.

LP: If only!

JC: Of course, that didn’t happen. Living standards have certainly gone up, but the values of capitalism—consumerism, individualism—remain incredibly powerful, and many of the problems of the system, such as inequality and monopoly, seem to have gotten worse. So, if you’re a reformist rather than a revolutionary, you have to acknowledge that failure. And it pushes you toward policies that aim to soften capitalism’s harder edges—things like a stronger social safety net, robust environmental regulation, and more protections for workers. But I don’t think we can assume that people will naturally grow out of capitalist values. That doesn’t seem to be happening.

LP: Maybe that reflects who we are as human beings. We contain both positive and negative qualities. We function as communities, but we’re also individualists. Those contradictions are deeply embedded in us.

JC: I think you’re right. Capitalism taps into some deep human instincts—whether they’re socially transmitted values or fundamental behavioral traits, I’m not sure. But that doesn’t invalidate the case for reform. These tensions don’t negate the arguments for better policy. They just make the work harder.