This post is part of an INET series on BRICS and the global economy. The series is written by authors of the New Development Bank’s report, “The Role of BRICS in the World Economy & International Development.”

About three years ago, the global development community adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as benchmarks to achieve by 2030. They replaced the Millennium Development Goals and emphasized several features—notably, a more universal consideration of development goals that doesn’t limit concerns or responsibilities to developing countries only. Development involves the expansion of effective human freedoms, including the capacity to avoid poverty, to be healthy, and to be equipped to participate in the life of one’s society. In the last 40 years, the collection and availability of survey data has allowed researchers to have a much better sense of trends in global poverty and inequality. In this short piece, I examine trends in inequality and poverty and the contribution of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) countries to reducing global poverty and inequality[1]. To do so, I use data from the Global Consumption and Income Project.

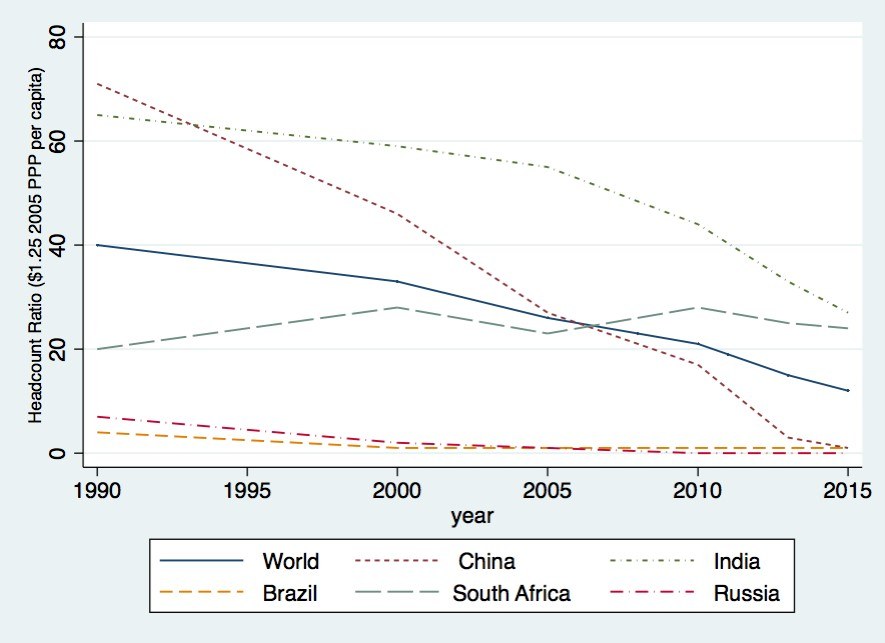

At the outset, it is useful to recognize the massive reduction in global poverty over the last 30 years. Figure 1 below shows the dramatic reduction in poverty across the world in the recent past. In 2000, 33% of the world was considered poor by this standard. By 2013, only 15% lived below this level. Most of this striking decline in global poverty has been due to the rapid economic growth in China and, more recently, India. Given their populations, these two BRICS countries have accounted for most of the decline in the global poverty headcount. Poverty (as defined by the $1.25 2005 PPP poverty line) in China declined between 1990 and 2013 by 68 percentage points, in India by 32 percentage points, and in the world as a whole by 25 percentage points. In absolute terms, the number of individuals deemed as poor declined from 805 million to 40 million in China and from 565 million to 422 million in India. The number of poor in the world declined by 1.04 billion (from 2.11 to 1.07 billion). Out of the 1040 million fewer poor, 908 million came from China and India together.

Table 1 shows the total number of and population share of people living below the poverty line in the BRICS countries in 2013 (the most recent year for which we can make a common estimate for the five countries and for the world as a whole based on the same poverty line). 477 million people or 15% of the population are still poor in the BRICS countries, accounting for 45% of global poverty. It is clear from this statistic that a very large share of the responsibility for continued global poverty reduction still rests with the BRICS. In the rest of the world, the share of people living below the poverty line was also 15% with 573 million individuals living in poverty.

Figure 1: Global Poverty Headcount Ratios at $1.25 Poverty Line (2005 $ PPP)

Source: Global Consumption and Income Project (see Lahoti et al., 2016)

Table 1: Poverty in BRICS Countries in 2013 According to the $1.25 2005 PPP Poverty Line

| Country/Region | Headcount Ratio (%) | Headcount (in millions) |

| Brazil | 1 | 2 |

| Russia | 0 | 0 |

| India | 33 | 422 |

| China | 3 | 40 |

| South Africa | 25 | 13 |

| BRICS Group | 15 | 477 |

| World | 15 | 1050 |

Source: Global Income and Consumption Project

The remarkable economic growth in BRICS countries in the last few decades has meant that they now have many fewer people living in poverty. But is this sufficient to achieve a world of zero global poverty by 2030? Clearly this is dependent both on the expected rate of growth and the chosen poverty line. Researchers have argued that the $1.25 poverty line is a very stringent one. As a result, poverty levels are negligible in many countries when using the $1.25 line, including Brazil and Russia, but are notably higher when other slightly higher lines are applied). Researchers therefore have argued for the adoption of a higher, more plausible poverty line or for alternative approaches to identifying the poor (see, for example, Reddy and Lahoti 2016, Reddy and Pogge 2003). In recognition of these concerns, one can examine how much growth would be required to achieve zero global poverty in different regions using the $1.25 PPP line as well as a more expansive $2.50 per day (2005 PPP) poverty line for moderate poverty and a $4.16 per day (2005 PPP) standard based on the amount that would be needed to have sufficient resources for nutritionally adequate food intake using US market prices.

Table 3 gives the survey mean growth rates in per-capita consumption required to get to zero poverty as defined by these various poverty lines by the year 2030.[2]

The required growth rates to eradicate poverty in some cases are implausibly large when compared to historical and recent growth rates, especially but not only for sub-Saharan Africa. An important caveat is that survey-mean growth rates (on which poverty estimates and middle class estimates are based) have been historically far lower (on average half) of national income accounts growth rates. In Table 3, we have assumed that growth rates of consumption in the surveys from which distributional and poverty data are collected will be the same as the projected growth rate, corresponding to consumption per capita in the national income accounts[3]. However, even so, the projected growth rates, when applied to an unchanging distribution, will not suffice to eradicate poverty by 2030.

Table 3: Annual Per-Capita Consumption Growth Rates (percentages) of Survey Growth Rates Required to Eliminate Poverty by 2030 for Different Poverty Lines

| $1.25 | $2.5 | $4.16 | |

| Brazil | 1 | 6 | 10 |

| China | <1 | 6 | 10 |

| India | 4 | 9 | 13 |

| Russia | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| South Africa | 6 | 11 | 20 |

| BRICS | 4 | 9 | 13 |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 4 | 8 | 12 |

| West Asia and North Africa | 7 | 12 | 21 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 11 | 17 | 29 |

| World | 9 | 15 | 21 |

| Source: Global Consumption and Income Project. |

Therefore, while growth is essential, it will nevertheless be insufficient to eradicate global poverty by 2030. A more fruitful way of achieving poverty eradication and serious reductions in deprivation is to foster more inclusive growth (interpreted here as growth that raises the incomes of the less affluent more). Growth processes that distribute the gains very broadly may emerge in different ways. For example, ensuring that steps that improve the education and human capacities of the poor or increase access to markets through better infrastructure are pre-market measures that facilitate meeting the market on more advantageous terms. And, steps that ensure that market transactions happen on equitable terms or that surpluses from production activities are equitably shared are in-market measures. Post-market measures are transfer mechanisms based on taxation and supplementation of earned incomes. These may have a role in ensuring that growth processes are able more rapidly to reduce poverty and deprivations and contribute to shared prosperity. Even rapid growth will need to be complemented by suitable sharing of gains to achieve global development goals.

Ensuring lower relative inequality is also in and of itself a Sustainable Development Goal recognized in the 2030 Agenda. BRICS countries have played a prominent role in imagining a path towards more widespread prosperity. Official attention to the ideas of inclusive growth and development in India and that of a harmonious society in China over the last fifteen years reflect this recognition.

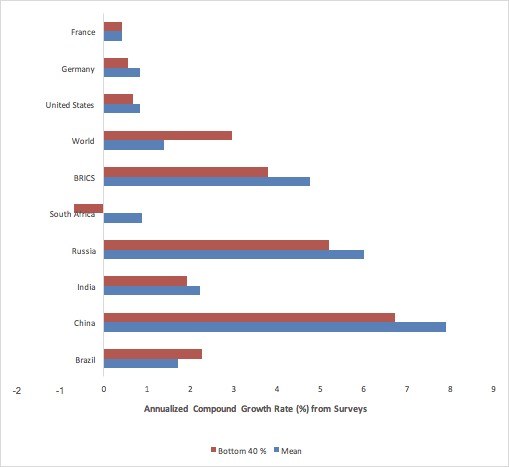

One of the SDG inequality indicators is the growth of the bottom 40% of the income distribution as compared to the national average. Figure 2 provides an indication of the growth of the bottom 40% relative to the national average in all the BRICS countries and across the world between 1990 and 2013. Apart from Brazil, the growth rate of the bottom 40% in the BRICS countries has been substantially lower than that of the mean. That noted, in the world overall, the large growth in the average incomes of China and India has meant that the growth of the bottom 40% worldwide was higher than the mean. The figures reported are for growth rates of survey incomes and therefore are different from national income per capita growth rates as reported from national accounts.[4]

Figure 2: Annualized Compound Growth Rates (%) of Survey Mean Income and Income of Bottom 40% from 1990 to 2013

Source: Global Consumption and Income Project.

Another way of putting this is that the relatively rapid growth of China and India has meant that global inequality has been falling in the last two decades due to decreasing inter-country relative differences. As a result, a greater proportion of global interpersonal inequality is now due to differences within countries than in the past. In 1980 about 78% of global consumption inequality derived from the differences between countries rather than from differences within countries. By 2010, inequality derived from differences between countries had declined to about 56%.[5] Between 1990 and 2013 mean per capita consumption growth in BRICS countries[6] substantially outstripped both that in developed countries and in the world. Continued BRICS growth (most dramatically in China and India) will further reduce global inequality, but we should also note that the gap between the better performing emerging markets and developing countries, or EMDCs (such as China), and the poorest is widening because of their differential growth rates. China’s per capita income from survey measures has increased from 1.18 times that of sub-Saharan Africa in 2000 to 3 times that in 2015. Although the BRICS’ primary contribution to reducing global inequalities is through their own development, this also suggests a need and rationale for BRICS to support development elsewhere, and in poorer developing countries.

The need to reduce poverty and promote more inclusive growth requires a two-pronged effort on the part of the BRICS. First it requires suitable internal social and economic policies aimed at the broad sharing of future gains in prosperity. Second it requires external engagement by the BRICS individually and collectively. This can take the form of supporting EMDCs, especially those which are poorer or have more limited technical capabilities, in their development paths, through mechanisms including development assistance, the transfer of ideas and knowhow through technical cooperation, FDI and other means. The BRICS also have an important role to play in actively creating a world more supportive of development. Such measures can simultaneously benefit the people of the BRICS countries and of EMDCs generally. Addressing structural inequalities in the world system is itself an important contribution to global development goals.

Inclusive growth and development can, as noted already, be achieved through pre-market, in-market and post-market measures. While social programs to ensure widespread sharing of the fruits of growth are important, inclusive growth and development is likely to require measures that allow market processes to generate more inclusive outcomes. Secure employment opportunities are less widespread, both geographically and sectorally, than is desirable. Informality of labour markets, large-scale migration, and other phenomena reflect this reality. The International Labour Organization (ILO) reports that 670 million jobs will need to be created by 2030 to keep pace with the growth of the working-age population.[7] This is a major concern, as the ills of premature deindustrialization, combined with jobless growth, have been widely reported and analyzed (see e.g. Rodrik 2015). There is growing apprehension that the traditionally conceived structural transformation in the form of a shift from agriculture to higher productivity sectors (typically in manufacturing) is no longer very much evident in many countries. Across the world, agriculture is shrinking and urbanization is taking place, but the service sector rather than the manufacturing sector is growing. Moreover, much of the growth in the service sector is in lower value-added forms of employment.[8]

Many middle- and low-income countries, including Brazil, South Africa and India, have been experiencing a weak link between output and employment increases. Others are in danger of experiencing a deindustrialization that again increases reliance on primary exports (see Castillo and Martins 2016 and Rodrik 2015). If manufacturing shrinks without a corresponding rise in high productivity service employment, informality and “precarity” increase and economy-wide productivity is reduced. There is evidence of such shifts both in Latin America and Africa (see McMillan and Rodrik 2011). The prevalence of large labour pools facing poor employment prospects, low job quality and limited socio-economic mobility is a weakness in many EMDCs and may play a role in deepening inequality worldwide. There are likely to be considerable gender disparities as well, since women are often more marginalized than men in labour markets. There is an urgent need to reorient growth to support just, desirable, secure and reasonably paid employment.

Within their announced commitment to inclusive and widespread growth, the BRICS have explicitly included respect for environmental boundaries and constraints. Understandably, the major focus of the BRICS over the last few decades has been to ensure relatively fast growth to reduce deprivation. There is now, however, the increasing recognition that the current global growth patterns have resulted in widespread environmental degradation in the form of water shortages, inadequate sanitation, deforestation, air pollution and carbon emissions that contribute to global warming among many other difficulties. Development is likely to continue to have a heavy impact on the physical limits sustaining the Earth as an ecological system. Catastrophic environmental threats generated by this impact are not only bad for future generations but have an adverse effect on current output through such effects as extreme weather and social dislocation. All of this requires conscious and concerted responses in terms of national policies and investments, which must in turn be supported by global efforts.

References

Banerjee, Abhijit V., and Esther Duflo. 2008. ‘What Is Middle Class About the Middle Classes Around the World?’ Journal of Economic Perspectives 22(2): 3-28.

Castillo, Mario, and Antonio Martins. 2016. ‘Premature Deindustrialization in Latin America.’ UN: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, http://www.cepal.org/en/public…

Jayadev, Arjun, Rahul Lahoti, and Sanjay G. Reddy. 2017. ‘The Middle Muddle: Conceptualizing and Measuring the Global Middle Class’. Forthcoming in A Just World: Essays in Honor of Joseph E Stiglitz. New York: Columbia University Press.

Jayadev, Arjun, Rahul Lahoti, and Sanjay G. Reddy. 2015. ‘Who Got What, Then and Now: A Fifty-Year Overview from the Global Consumption and Income Project’. A Working Paper from the Department of Economics. The New School for Social Research, New York. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2602268 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2602268

McMillan, M. S., and D. Rodrik. 2011. ‘Globalization, Structural Change and Productivity Growth’. Working Paper 17143, National Bureau of Economic Research, Washington, DC.

Milanovic, B., and Shlomo Yitzhaki. 2002. ‘Decomposing World Income Distribution: Does the World Have a Middle Class?’ Series 48, Number 2, 155-178. Research Department, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Reddy, Sanjay, and Rahul Lahoti. 2016. ‘$1.90 a Day: What Does It Say? The New International Poverty Line’. New Left Review 97: 106-127.

Reddy, Sanjay G., and Thomas W. Pogge. 2003. ‘How Not to Count the Poor, Version 4.5.’ In: Sudhir, Anand, Paul Segal, and Joseph Stieglitz, eds. 2010. Debates on the Measurement of Global Poverty. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rodrik, D. 2015. ‘Premature Deindustrialization’. Working Paper 20935, National Bureau of Economic Research, Washington, DC.

Stiglitz, Joseph E., and Bruce Greenwald. 2015. Creating a Learning Society: A New Approach to Growth, Development, and Social Progress. New York: Columbia University Press.

United Nations. 2017. ‘Progress Towards the Sustainable Development Goals’, Sustainable Development Goals Report, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/re…

Footnotes

[1] This essay extracts heavily from a background report to the New Development Bank in 2017.

[2] Due to the previously noted discrepancy between national income and survey income growth rates, the per capita growth rates required to eliminate poverty will likely have to be even higher than estimated in Table 3.

[3] If the discrepancies between survey mean growth rates and national income accounts continue to be at their historical levels over the last three decades, the improvements in income levels and in poverty reduction as reported in the tables will be too optimistic.

[4] In particular, starting from the 1990 base, Russia has a steeper rate of growth of per capita consumption from surveys over the period than it did of GDP per capita as measured by national accounts, whereas the opposite is true for India.

[5] Calculation from Jayadev et al (2017) using the Theil index and based on Global Consumption and Income Project data.

[6] This is the case for the BRICS overall and for four out of five of the individual countries. The BRICS overall and two of the five individual countries also outstripped world median per capita consumption growth.

[7] http://www.waipa.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/ILO-Presentation-SDGs-Investment-and-Decent-Work.pdf

[8] See among others, Stiglitz and Greenwald (2014) on such transitions.