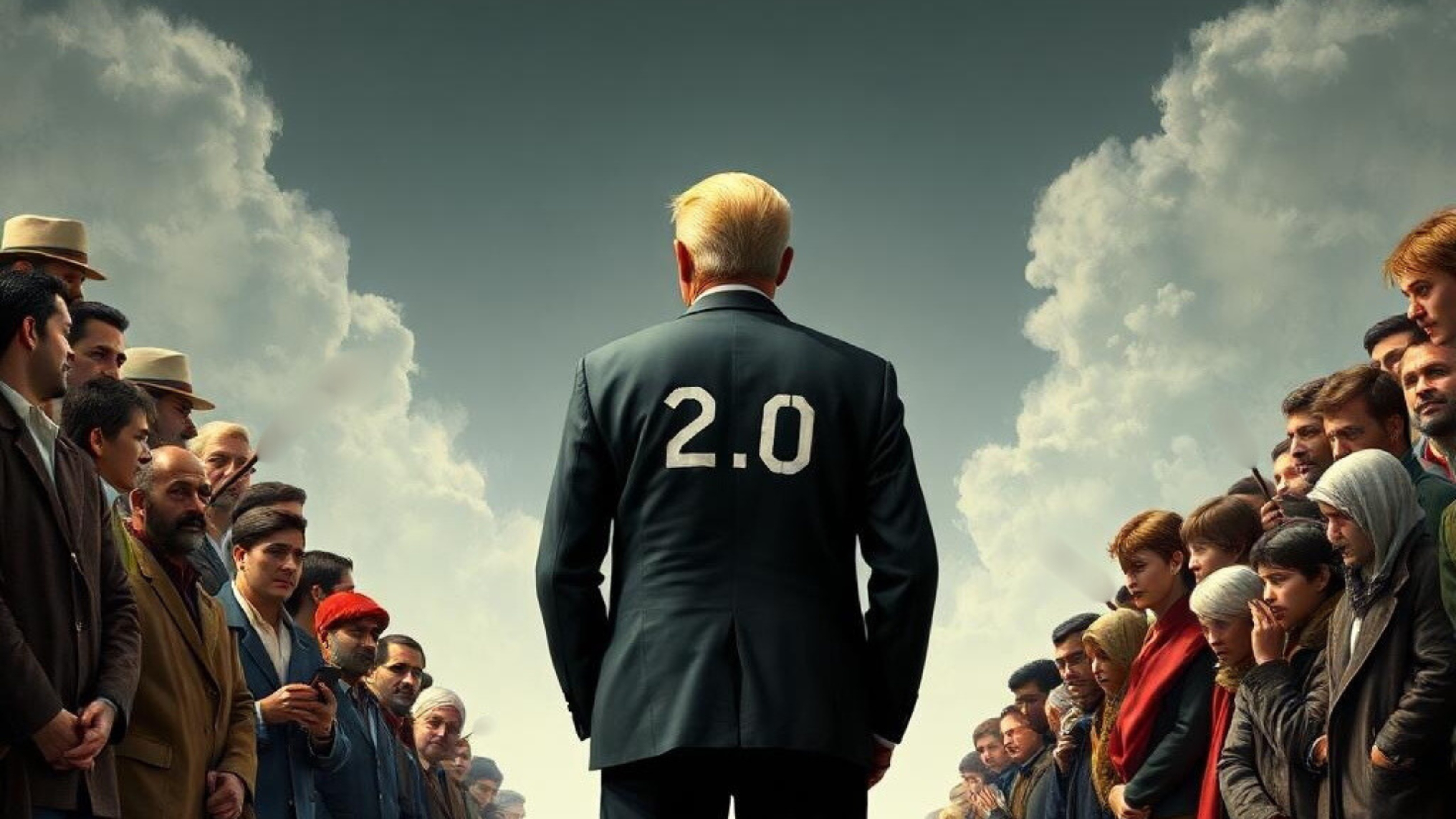

The most likely outcome of the second Trump administration is a recession and an exacerbation of inequalities, and a further degradation of the living standards of working and middle-class Americans.

The past few weeks have been marked by Donald Trump’s announcements of higher tariffs on nearly all of the United States’ trading partners. These tariffs have been justified under an “America First” agenda, which aims at bringing manufacturing jobs back to the U.S. and—according to the populist wing of the Trump coalition—restoring the position of the American middle class.

The rollout of these tariffs has been, to say the least, erratic. Initially, there were increases on imports from China, Mexico, and Canada—some of which were later postponed. This was followed on April 2nd—referred to as “Liberation Day”—by a sweeping hike in tariffs on nearly every trading partner of the U.S., prompting retaliatory measures (e.g., by China and the European Union). The resulting meltdown in financial markets led to a new postponement of the increases for every country except China, for which the tariffs rose even further. In response, China expanded its tariffs on U.S. imports. As of the time of the writing of this piece, the last episode of this drama was the announcement that key electronic product imports from China, as well as cars and car parts, would be exempt from the increases.

An important question related to these developments is what their distributional consequences will be. Are the promises for a regeneration of the American middle class credible? One could argue, for example, that since the ownership of financial assets is very unequally distributed, the stock market crash of the last weeks is either irrelevant—as the stock market does not represent the real economy—or even beneficial from a distributional point of view because it disproportionately affects high income/high net worth individuals.

In this note, we explain that such an outcome is unlikely. If we examine the effects of the new tariffs within the context of the wider policies of the new administration, the most likely outcome is a recession and an exacerbation of inequalities, and a further degradation of the living standards of working and middle-class Americans.

The US trade deficit

According to the Trump administration, the primary reason for the tariff increases is the large trade deficit of the U.S. economy. The U.S. emerged from World War II with a trade surplus and an overall balanced current account. The trade deficit did not appear until the late 1970s and continued to grow until the 2007 financial crisis, a trend that was briefly interrupted in the late 1980s following the Plaza Accord. Over the past fifteen years, the trade deficit has not returned to its pre-2007 levels, largely due to the rise of shale gas extraction and a significant improvement in the trade balance of petroleum products. However, the trade balance for goods excluding petroleum products remains at the same level as it was in 2006.

This long-term increase in the trade deficit—spanning more than four decades—has largely been the result of a deliberate strategy by U.S. capital to outsource production. This was driven by a dual goal: to access cheaper labor abroad and to discipline labor at home. This strategy has played a central role in the widening of inequality in the U.S. during the same period.

The U.S. dollar’s role as the international reserve currency has also contributed to the trade deficit. High global demand for dollar-denominated assets tends to strengthen the dollar’s exchange rate relative to other currencies. Additionally, U.S. policymakers have actively supported the dollar when it has been at risk of depreciating.

Neoclassical economists provided the intellectual justification for free trade and outsourcing production with models that emphasized their benefits. In these models, although it is recognized that removing trade barriers can have positive welfare effects on some economic actors and sectors and negative effects on some others, the net effect is positive. Thus, the “losers” can be compensated by the “winners,” who will be better off nonetheless.[1]

Neoclassical analysis suffers from two major shortcomings: it ignores the role of power, and it is largely static in nature, focusing on the allocation of resources while overlooking the dynamic and evolutionary aspects of capitalist economies. Because of these limitations, it failed to account for two crucial dimensions of the expanding trade deficit.

First, the benefits of free trade were very unequally distributed. The American consumer did benefit, but most of the benefits were concentrated at the top of the income distribution, as firms were able to increase their profits because of cheaper imports from abroad and disciplined labor at home. Meanwhile, the outsourcing of production severely harmed manufacturing workers, many of whom lost their jobs, and entire regions experienced deindustrialization and economic decline. The latter, the “losers,” were never compensated by the former, “the winners,” as the theory suggested. From this perspective, it is understandable that affected communities and manufacturing-sector unions have opposed free trade and supported tariffs.

Second, the process of a widening trade deficit involved a process of what Myrdal called “circular and cumulative causation” both in the U.S. and abroad. The increase in the trade surpluses of the U.S. trading partners in Asia and Northern Europe allowed them to upgrade their position in the global value chains and become much more competitive over this period. China stands as the prime example in this process. On the other hand, this process worked in the opposite way in the U.S. The hollowing out of the manufacturing sector and its production networks has made it increasingly difficult to reshore production. In other words, due to economies of scale and other dynamic factors, the decision to outsource production is not symmetrical to that of reshoring. Simply raising trade barriers will not automatically bring back the manufacturing jobs that were lost when those barriers were initially removed.

More generally, the fact that neoclassical economics is wrong when it suggests that the removal of trade barriers is always beneficial and leads to welfare improvements does not make the opposite true, namely, that raising trade barriers is always beneficial and leads to welfare improvements. Thus, the effect of tariffs depends on the structural characteristics of each economy as well as on other policies that accompany them. Depending on them, they can be beneficial or harmful—for the economy as a whole or for specific groups within the economy. In the case of the U.S. economy, the change in the structural characteristics of the manufacturing sector over the last decades makes it possible that those who lost from the push for laissez-faire will also lose from the increase in tariffs. We are coming to this below.

Short-run distributional effects of tariffs

We now turn to the distributional effects of tariffs. In the short run, the real impact of tariffs on net exports will be limited, as the potential to substitute imported goods with domestic alternatives is minimal. Whatever margin for substitution does exist—leading to a reduction in U.S. imports—will be offset by the counter-tariffs announced by U.S. trading partners, which will in turn reduce U.S. exports.

On the other hand, higher tariffs lead to increased costs for imported goods. The last time the U.S. economy faced a broad-based import price shock was in the aftermath of the pandemic. As we found in a recent paper—consistent with several other studies—American corporations were able to defend or even raise their markups in response to that shock, passing the cost increases onto domestic prices. The result was domestic inflation and pressure on the real incomes of the working and middle classes.

To the extent that this time around firms will also be able to defend their profit margins—it is not clear what has changed compared to three years ago—the immediate distributional results of the tariffs will be analogous: rising domestic prices and real income losses for the middle class.

As we have explained in another paper, the distributional effects in response to shocks in import prices can also have significant macroeconomic effects. Since the propensity to consume of the working and middle classes is very high, the real income losses due to price increases have a negative effect on consumption and aggregate demand (a point we will return to below).

The budget

It is often said that a government’s true intentions are revealed by its budget. This is especially true in the case of the recent budget approved by Congress with the backing of the Trump administration. One cannot discuss the administration’s priorities without referring to it.

The budget bill includes trillions of dollars in tax and spending cuts. However, the tax cuts will primarily benefit high-income households and corporations, while the spending cuts will disproportionately affect low- and middle-income households. These include reductions to Medicaid, nutritional assistance programs, the layoff of hundreds of thousands of federal employees, and the dismantling of entire government agencies. Clearly, these policies will result in a significant redistribution of income from lower- to higher-income households.

According to recent estimates by the Yale Budget Lab, the average after-tax-and-transfer income of households in the bottom quintile and second-to-bottom quintile is expected to decrease by 5% and 1.4%, respectively. On the other hand, households in the fourth and top quintile will see their incomes increase by 1.4% and 2.5% respectively. These losses are on top of the estimated reduction in median household income by 2.8% due to tariffs. As noted by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the estimated losses of the bottom quintiles are likely conservative, as they do not account for cuts overseen by the House Education and Workforce Committee, which are expected to affect student loan repayment conditions.

The provisions of the budget bill are difficult to reconcile with the neo-populist narrative that the Trump administration seeks to defend the American working and middle class. Instead, the bill follows the precedent set by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which had regressive distributional effects, and will lead to a further increase in income inequality in the U.S.

Macroeconomic effects

This brings us to the potential macroeconomic effects of the new administration’s trade and fiscal policies. As already noted, net exports are relatively inelastic in the short run, and whatever decrease in imports achieved through higher tariffs will likely be offset by a corresponding decrease in exports due to reciprocal tariffs imposed by U.S. trading partners.

In addition, the redistribution of income away from working- and middle-class households—resulting from both the new budget and the inflationary impact of tariffs—will negatively affect consumption, as low- and middle-income households have a much higher propensity to consume than those at the top of the income distribution. Furthermore, the recent drop in the stock market, along with continued volatility, may contribute to a negative wealth effect, further suppressing consumption.

Government spending growth is also set to slow down in line with the budget, removing another potential source of demand.

This leaves private investment as the only remaining component that could drive economic growth. But is it likely that investment will surge in response to the recently adopted tax cuts and offset the negative pressures on consumption and government expenditure? The answer appears to be no. The consensus regarding the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017—which was similarly justified on the grounds that lowering tax rates for wealthy households and corporations would boost investment—is that it had a small effect on output and investment. There is little reason to believe that tax cuts would be more effective this time.

Moreover, the highly uncertain economic and political environment is likely to dampen the “animal spirits” of entrepreneurs and weigh further on investment. As a result, not only is an investment boom unlikely, but investment will most likely slow down or even decline, placing even more downward pressure on aggregate demand.

Overall, this analysis suggests that it is unlikely that the U.S. economy will avoid a significant slowdown, while the probability of a recession is not negligible.

Two related points are worth noting. First, an economic slowdown will likely reduce the trade deficit—achieving the administration’s stated goal, but for the wrong reasons. Second, the slowdown (or even more, a potential recession) and the accompanying increase in the unemployment rate will have further distributional consequences against wages.

The long run

One might finally argue that all of this is a bitter pill the U.S. economy must swallow in order to revive its manufacturing sector. While it is beyond the scope of this note to offer predictions about the long-term structural transformation of the U.S. economy, we can make three key points.

First, it is unlikely that tariffs alone—especially when implemented in such an erratic and ad hoc manner—will be sufficient to achieve the desired structural transformation of the U.S. economy and its manufacturing base. Such a transformation would require a broader and more coherent strategy, which has yet to be proposed.

Second, some of the stated goals and likely consequences of the announced trade policies risk undermining the dollar’s role as the international reserve currency. Sharp declines in U.S. asset prices and a devaluation of the dollar are inconsistent with its continued status as the hegemonic global currency. It remains unclear how the Trump administration intends to reconcile these contradictions.

Finally, a resurgence in manufacturing does not automatically translate into improved conditions for the working and middle classes. The era between the Civil War and the early 20th century—an era President Trump often idealizes—was indeed marked by high tariffs aimed at protecting U.S. manufacturing. However, besides the fact that at that time the U.S. was essentially a developing economy catching up with the very advanced European economies, this is exactly the period referred to as the Gilded Age, which was marked by very high inequalities. The reduction in inequality and the rise in living standards for American workers and the middle class came later, as a result of organized labor struggles and the policies introduced during the New Deal and the postwar period. The current administration has proposed no comparable policies—in fact, as we have noted, the budget appears to move in precisely the opposite direction.

Conclusion

The U.S. economy has undergone dramatic changes over the past few decades. Average growth rates of real GDP and productivity have declined, while income and wealth inequality have increased, and significant portions of industrial production have been outsourced. These shifts have left workers in many sectors economically insecure. However, the current trade and fiscal policies of the Trump administration—along with the erratic manner in which they are announced—are unlikely to address these issues. On the contrary, their most probable outcome is a worsening of inequality and the onset of a recession, accompanied by rising prices.

Note

[1] The possibility that trade might lead to net welfare losses arises, as in many aspects of neoclassical theory, when various rigidities or market imperfections are introduced. However, these were generally treated as special cases that did not undermine the central message: trade liberalization is beneficial.