Researchers and policymakers often argue that global perceptions of risk are a major driver of international capital flows, financial contagion, and sudden stops. In addition, business leaders often cite crises in foreign markets where they may produce their products, sell their products, or be otherwise exposed as holding up their investment and employment decisions. Although such notions of country risk and its transmission across borders feature prominently in policy circles and boardrooms, quantifying and analyzing global risk perceptions has proven more difficult.

Our new INET working paper aims to fill the gap and re-examine the conventional wisdom systematically by analyzing what global executives and investors say about the exposures, risks, and opportunities their firms face worldwide. In particular, we apply natural language processing (NLP) to the conference call transcripts of publicly listed firms around the world to build an index of perceived risks and opportunities relating to each of 45 major economies that collectively cover more than 90% of world GDP. The key advantage of this approach is its granularity: it allows us to separate global risks from those associated with particular countries, firms, and industries; distinguish variation in perceived risk from variation in perceived opportunities and sentiment; and separate the perceptions of foreign from domestic agents.

Measuring the perceived risks and opportunities of countries around the world from firms’ earnings call transcripts has a number of further advantages. First, it allows us to directly link country risk as perceived by global executives and investors to country-level capital flows, assets prices, and firm-level decisions. Second, by aggregating within-firm perceptions of countries, we can straightforwardly operationalize and test for the nature of contagion between foreign country risk and domestic firm-level investment and employment decisions. Finally, by aggregating across-firm perceptions of countries, we are able to measure, decompose, and diagnose sudden spikes in country risk.

After validating our measures, we use our new time series of country risk to document a number of new findings. First, we demonstrate that countries that become riskier in the eyes of global investors experience falling asset prices. In particular, increases in a country’s perceived riskiness is accompanied by sharp declines in equity prices and increases in equity volatility. We also show that elevated risk is associated with elevated CDS spreads and bond yields, with effects particularly strong in emerging markets. Second, we document a similar relationship between risk and global capital flows. In particular, we find that elevated levels of country risk coincide with foreign investors pulling capital out of the country; this result holds even conditional on country and year-quarter fixed effects, indicating that these flows are moving with country-specific fluctuations in riskiness. There is a large literature demonstrating the importance of “push factors” in explaining global capital flows. These push factors speak to the relative importance of common shocks, particularly in developing countries, in explaining global capital flows. Our analysis introduces a new force: we demonstrate the importance of a country-specific factor (“Country Risk”) in explaining capital flows. Third, because our country risk measures are based on granular firm-quarter-level data, we can decompose these aggregate findings into their source. We find that it is the perception by foreign firms rather than domestic firms that explains the patterns of capital inflows and sovereign credit spreads.

Having demonstrated the importance of country risk in explaining country-level asset prices and capital flows, we then turn to examining its importance for firm-level outcomes. In particular, we demonstrate that elevated country risk is associated with reductions in firm-level investment and employment of firms based in the country. This result holds even conditional on the firm’s own perceived risk as well as on firm and year fixed effects. We view this as providing strong evidence that fluctuations in perceived country risk are an important determinant of real firm outcomes, above and beyond firm-specific uncertainty.

We then move beyond the direct effect of a firm’s home country risk on corporate investment and employment and examine the transmission of foreign country risk across borders. Our key finding is that firm-level exposure to foreign risks affects firm level outcomes; moreover, it is highly heterogeneous and not well approximated by publicly observable financial variables. In particular, we introduce a firm-quarter level measure we call “Transmission Risk” which operationalizes in a straightforward way a given firm’s exposure to risks emanating from foreign countries at a given point in time. We demonstrate that when a firm’s transmission risk increases, it reduces its investment and employment, and experiences declines in its stock returns. This occurs above and beyond not just fluctuations in country risk of the firm’s own home country, but also the firm’s own measured risk. This provides clear evidence that perceived foreign risks spillover to both real decisions and the financial value of firms around the world. Notably, we show evidence that this kind of contagion often operates through complicated exposures that are not well-approximated by customer-supplier relationships or the firm’s observable foreign investments. In this way, we demonstrate that contagion (the spillover of foreign country risk on firm-level outcomes) is an important driver of firm decisions.

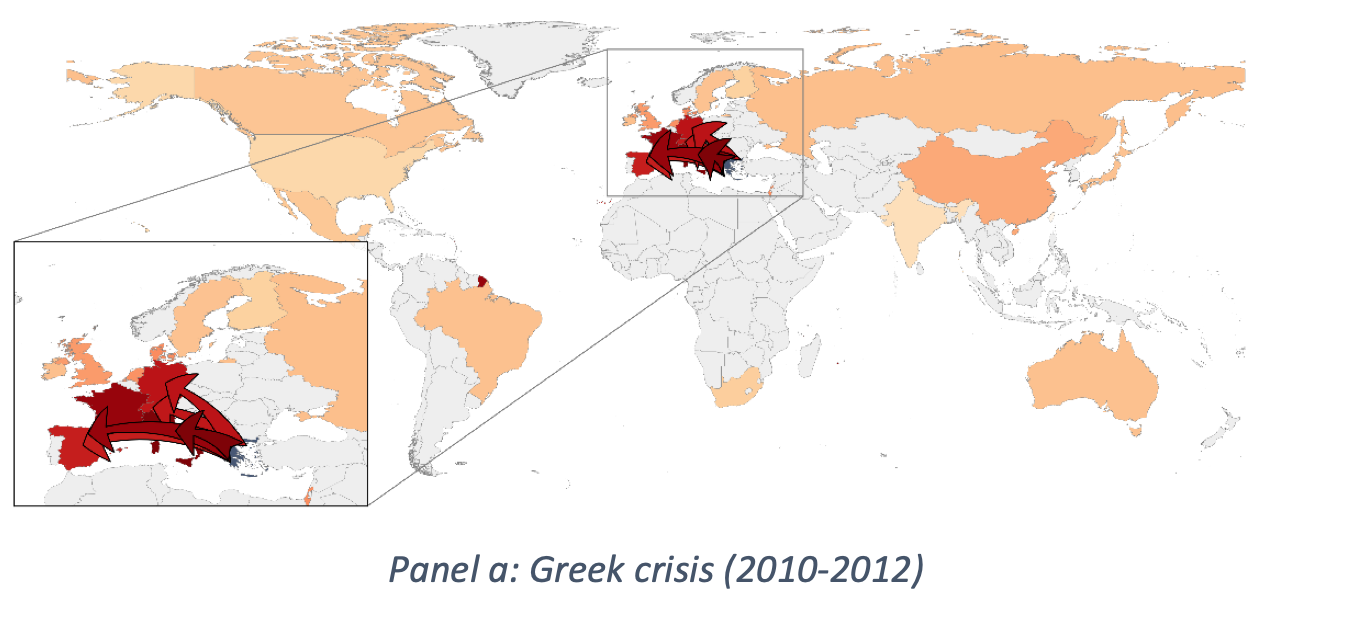

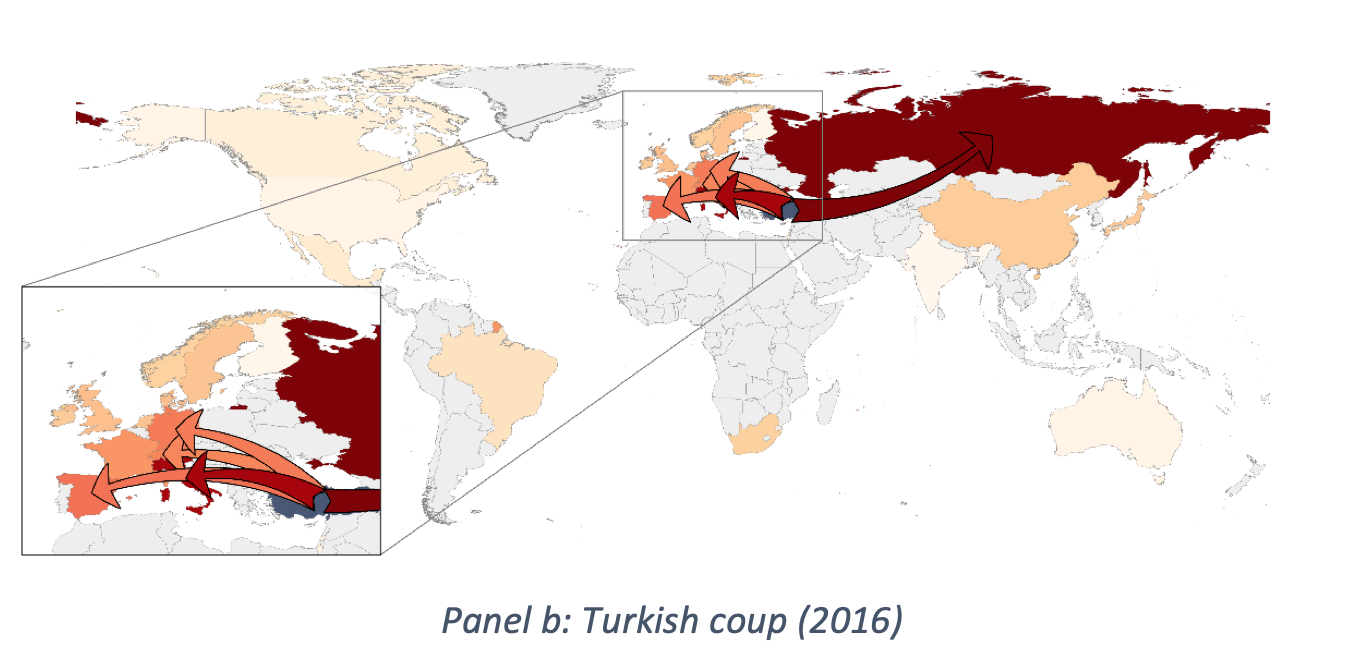

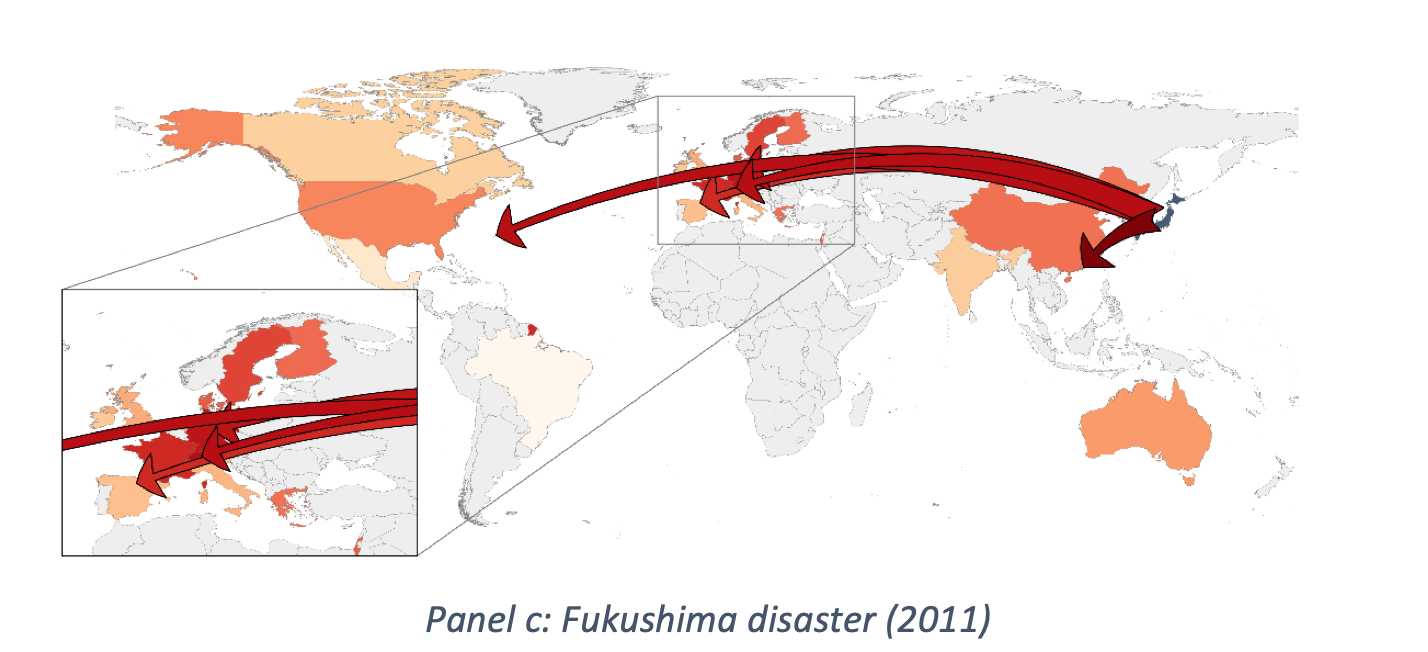

The granularity of our measures allows us to then analyze the nature of this pattern of contagion – or the firm-level transmission of global risk – by examining which firms are relatively more exposed to different countries around the world. We demonstrate that the patterns of transmission of risk around the world follow a gravity structure, with firms on average worrying more about risks in countries geographically closer to them, that speak the same language, and which were in a colonial relationship. To add texture to this analysis, Figure 1 focuses only on the Greek Financial Crisis (2010-2012), the coup against Erdogan in 2016, and the Fukushima nuclear disaster of 2011. It shows how risks from these crises are transmitted to firms across the globe. While the Greek crisis is of course transmitted predominantly to other EU countries, the Turkish coup raised most concerns among Russian and Italian firms, and the Fukushima disaster stands out for having disparate effects in all regions of the globe – ranging from Australian Uranium producers to the French component manufacturers already mentioned above, and insurance firms in Bermuda and Hong Kong.

Finally, we use our novel measures of country and global risk to add to the literature on the connection between global risk and exchange rates. We demonstrate that heterogeneous loadings on our text-based measure of global risk explain a large fraction of the cross-sectional variation in exchange rate movements and currency returns. Most notably, we provide direct evidence that the US dollar, the euro, and the Japanese yen systematically appreciate when global risk perceptions spike. These results provide strong evidence for a prominent theoretical literature, where our new measures of perceived risk allow us to examine the theories more directly than was previously possible.

Figure 1 Country Risk transmitted through firm exposures: Three examples.

Notes: This figure plots the countries in which firms have the highest average Transmission Riski,t during the following three crisis episodes: the Greek crisis in 2010-2012, the Turkish coup in 2016, and the Fukushima disaster in 2011. We also plot arrows to the top 5 countries with firms that have the highest average Transmission Risk[i,t]. For the Greek crisis, these are Italy, France, Germany, Switzerland, and Spain; for the Turkish coup, these are Russia, Italy, Spain, Germany, and Switzerland; and for the Fukushima disaster, these are Hong Kong, Switzerland, Bermuda, Germany, and France. Darker colors indicate higher Transmission Riski,t. Countries in grey indicate that we do not have >25 firms headquartered in that country during the episode.

Notes: This figure plots the countries in which firms have the highest average Transmission Riski,t during the following three crisis episodes: the Greek crisis in 2010-2012, the Turkish coup in 2016, and the Fukushima disaster in 2011. We also plot arrows to the top 5 countries with firms that have the highest average Transmission Risk[i,t]. For the Greek crisis, these are Italy, France, Germany, Switzerland, and Spain; for the Turkish coup, these are Russia, Italy, Spain, Germany, and Switzerland; and for the Fukushima disaster, these are Hong Kong, Switzerland, Bermuda, Germany, and France. Darker colors indicate higher Transmission Riski,t. Countries in grey indicate that we do not have >25 firms headquartered in that country during the episode.

Notes: This figure plots the countries in which firms have the highest average Transmission Riski,t during the following three crisis episodes: the Greek crisis in 2010-2012, the Turkish coup in 2016, and the Fukushima disaster in 2011. We also plot arrows to the top 5 countries with firms that have the highest average Transmission Risk[i,t]. For the Greek crisis, these are Italy, France, Germany, Switzerland, and Spain; for the Turkish coup, these are Russia, Italy, Spain, Germany, and Switzerland; and for the Fukushima disaster, these are Hong Kong, Switzerland, Bermuda, Germany, and France. Darker colors indicate higher Transmission Riski,t. Countries in grey indicate that we do not have >25 firms headquartered in that country during the episode.