Edit 04/11: meeting of mind. there was a session on just the same topic yesterday at the Kilkeconomics festival, by Peter Antonioni. If any visitor attended, please complement or summarize what was said there.

I’ve thus been looking for a way to bring the urban “field” into the classroom, if not a real one, at least a realistic one. Not a stylized field where the economic dimension of behaviors is readily apparent. Just like in the real world, it had to be intermingled with sociology, psychology and geography.

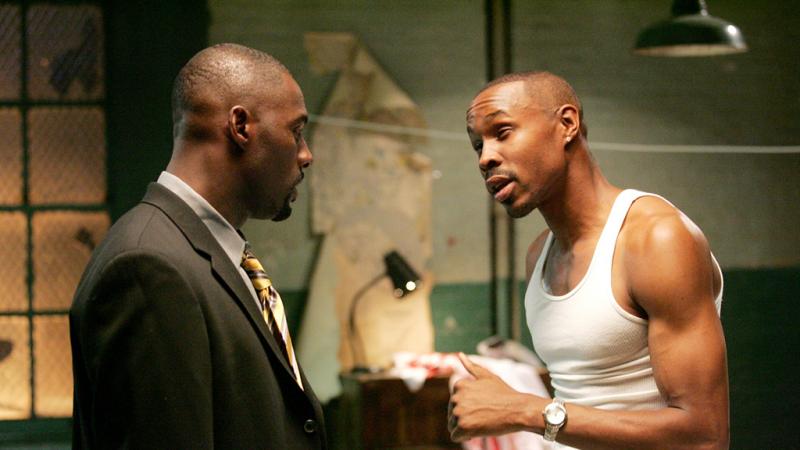

Baltimore is such a field, and the purpose of HBO success series The Wire (2002-2008) is to depict in a fictionalized yet realistic way — so critiques say — the daily interplay of a hundred of its characters, ranging from drugs dealers (focus of seasons 1 and 3), dockers and labor union leaders (season 2), police officers, judges and public attorneys, town councelors and mayors (seasons 3 and 4), public school teachers (season 4) and journalists (season 5). These characters are social agents: they work or, more often, are unemployed, they consume, trade, compete, save, invest, borrow, innovate, bet, devise strategies, build reputations. They make choices, all the time. Sometimes their behaviors rely on economic motives, sometimes other interests or emotions win over.

The Wire features characters who think as economists predict, and others who, under similar circumstances, behave as sociologists or anthropologists describe. One of the most powerful drug gangs, the Barksdale organization, is led by Avon Barksdale with the help of Stringer Bell. Confronted to wars over turfs, to the decreasing quality of their product, and, at the beginning of Season 3, to the loss of their territory ( the Franklin towers), the two characters react very differently. While Avon seeks to recruit hitmen to enforce control over West Baltimore and repeatedly explains to Stringer that, being “just a gangsta,” he praises such control for the sake of power, whatever the price. Stringer Bell, on the other hand, embodies the “businessman,” as Avon says. Stringer attends economic lectures, and seeks to apply them to the drug business: he trades territory for higher quality heroin, creates a retail coop with competing dealers to secure the supply of high quality drug and to internalize the costs of the settlement of conflicts over turf (the costs of external settlements are high : street murders and associated police investigation, arrests, etc.). He launders drug money through real estate investment. Displaying the confrontation between the two men in both econ and socio lectures may thus help counter the old student’s complaint that “this is not realistic, ma’am. People don’t behave like that/ people have other motives.”

In this project, my sociology and geography colleagues can build on existing blueprints: The Wire is used at Harvard and UMontreal to teach urban sociology, at Duke to teach class inequality. The series is the subject of several scholarly papers and dedicated conferences (and that one in French) and seminars. On the contrary, there is very little material on how to teach economics with The Wire. Presumably because the economic method is rather based on the careful analysis of quantitative data rather than field observation. Maybe because a fiction is not the right way to show the “field” in economics. Possibly because there’s not even such a thing as “field” in econ. And ultimately, because, as I quickly discovered, the series is not the best exemple of how ‘principles of economics’ rule in real life.

- In The Wire, nothing’s pure, nothing’s perfect: neither competition, nor information. Dealers and junkies are anything but price takers. The series is fit for urban economics (next year’s project), public choice theory, and especially fit for industrial organization (see that post from younotsneaky) and for game theory. And it almost systematically violate ‘the principles.’ Dealers avoid competition at any rate, through location and product differentiation. Price competition surfaces only once, when Barksdale dealers share their territory with Prop Joe’s dealers. Dealers collude, with incentives to defect. There are games between dealers and the police, and then attempts to turn ‘the game’ (the most important word in the show, that’s how dealers call their activity) into a cooperative one, when officer Colvin opens legal areas to sell drugs. There are repeated games between police officers and local politicians (the Carcetti-Burrell confrontation over crime statistics in season 3). Depending on how the student models the rules of the game and the payoffs from a given scene from The Wire, he’ll end up with a prisoner’s dilemma, a chicken or ultimatum game, and you can introduce him to cooperative and non-cooperative, one-shot and repeated, zero-sum and non zero-sum, symmetric and asymmetric games. Hence the recurring question: is it possible to introduce students to economic reasoning without teaching them the yardstick (neoclassical equilibrium) first?

- Economics is about individual behaviors, including macroeconomics which is, for better or for worse, microfounded. Yet, when journalists and social scientists talk about the economics of The Wire, they usually refer to its implicit critique of ‘capitalism’ (as David Simon, creator of the series, himself claims). For them, capitalism seems to be just another word for “economic system.” Yet, the word is barely used in economics today. I taught for 10 years without using it except in economic history lectures and broad narratives in which I relied on the French regulation school to explain the impact of financial regulation on the economy. Some colleagues told me that the term was outcast because of its ideological load. Yet, capitalism originally means how the production of wealth is organized (and yet it’s not used in courses on long term production and growth), and by extension how economic activities are regulated. The Wire is about the consequences of economic forces which are anonymous, external to the field, which explains why “capitalism” makes sense. So far, I’ve failed to make sense of this viewpoint in my classes.