Recent headlines about year-over-year consumer prices sensationalize with phrases like “worst inflation in 40 years” and “out-of-control inflation.” The reality of high inflation, its real costs on many American households, and the extensive, sometimes excessive, media coverage has been a drag on Biden administration approval and is among the most prominent talking points in the Republican effort to take control of Congress in the November midterms.

In this environment, it is no surprise that Democrats labeled their hard-won and much watered-down legislative victory the “Inflation Reduction Act” (IRA, for short). Yes, the bill contains some pieces that reduce prices, including authorization for Medicare to negotiate prices of some widely used prescription drugs and initiatives to increase the supply of renewable energy over time. But in terms of the inflation data driving today’s news, the impact of the IRA on inflation will be minimal, as predicted by some model-based estimates.[1]

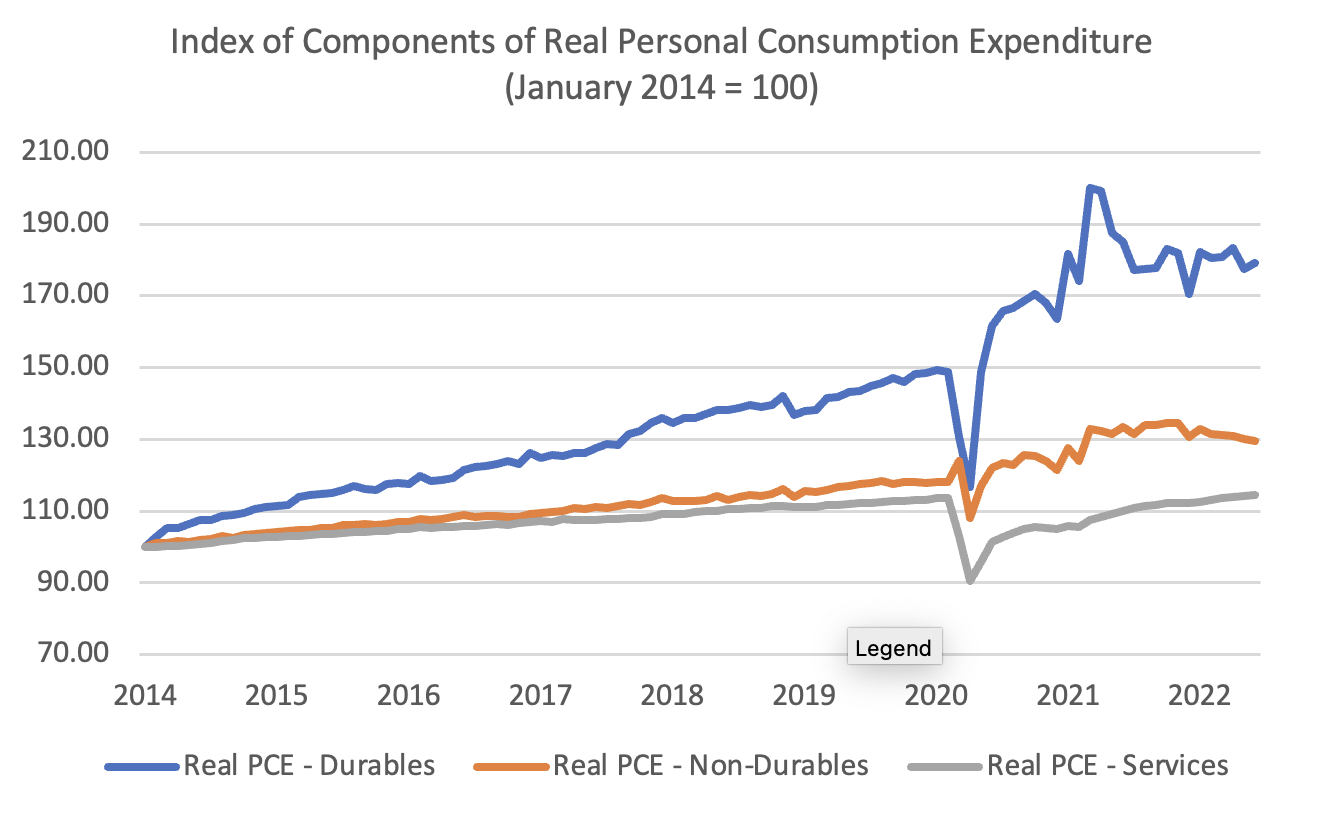

While one might criticize the act’s politically motivated name, it is important to recognize it is likely almost impossible to design an effective fiscal policy to address the recent inflation spike. The high inflation of 2021 and 2022 arose from the enormous economic disruptions caused by the pandemic and were magnified by the Ukraine war. Prior to the Covid-19 crisis, market-driven responses of supply chains to modest economic shocks prevented large shortages: supply almost always adjusted reasonably quickly to the changing composition of demand. But supply chains could not adjust quickly enough to the gut punch of the pandemic disruption. For example, the chart below shows the massive increase in volatility of components of real personal consumption, especially durable goods, that began with the pandemic.

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis retrieved St. Louis Federal Reserve database. Data codes PCEDGC96 (durables), PCENDC96 (non-durables), and PCESC96 (services).

The inability of supply chains to adjust to huge changes in the allocation of demand caused historic pressure on relative prices. A change in relative prices does not have to cause overall inflation, in principle. But the only way it would not cause higher inflation is if the prices of items less in demand fall to offset the increases in prices of items for which demand exceeds restricted supply.

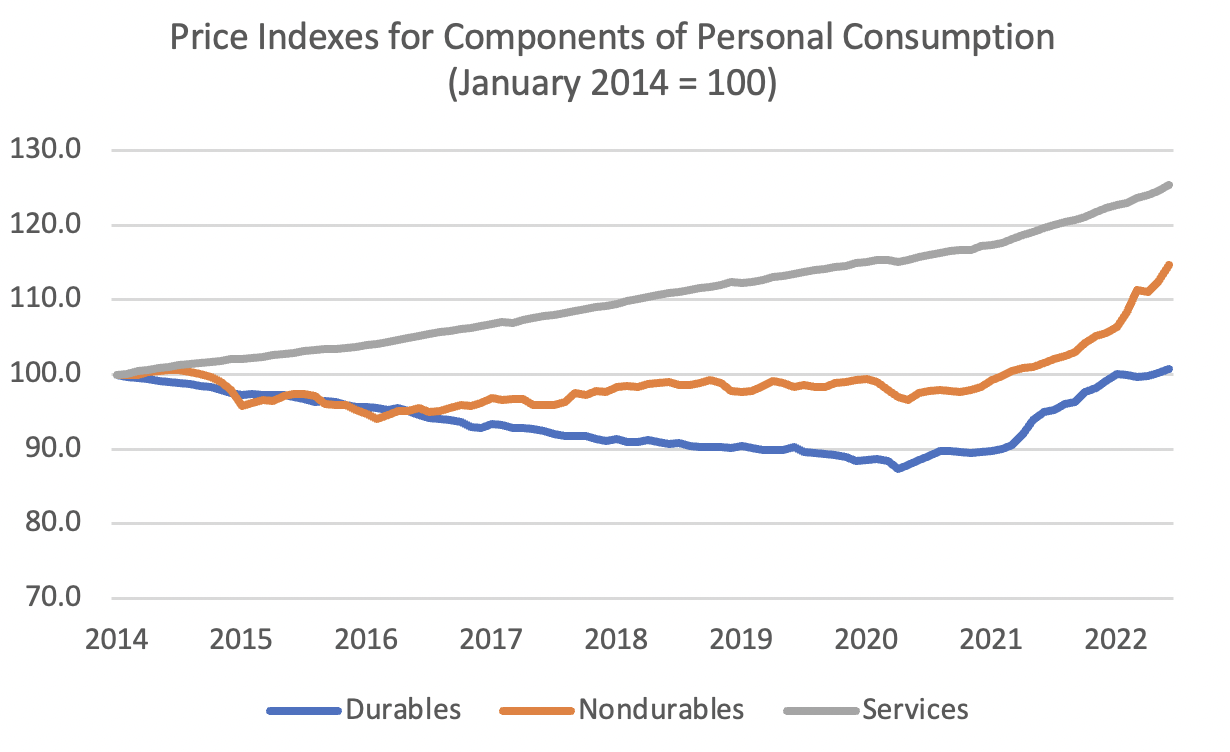

The chart below shows this offset did not occur. As one would expect, durable and nondurable prices rose much faster when demand for these items increased rapidly as the economy bounced back from the initial pandemic lockdown. And the Ukraine war accelerated the price increases for nondurables, which include energy and food consumption. Did the price of services, which account for about two-thirds of personal consumption, fall to offset the rise in the prices of goods? The chart shows the answer is a strong no. Service prices largely followed their pre-pandemic trend. In fact, service price inflation rose somewhat as costs of some inputs into service production (energy, for example) rose quickly. If the prices of some things people buy rise a lot and the prices of others things remain on their long-term trend, the result has to be inflation.

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis retrieved St. Louis Federal Reserve database. Data codes DDURRG3M086SBEA (durables), DNDGRG3M086SBEA (non-durables), and DSERRG3M086SBEA (services).

The economy continues to adjust to these big shocks. Recent data shows some moderation in inflationary pressures. But the adjustment is taking a long time, longer than many analysts (myself included) expected a couple of years ago. But, in retrospect, considering the enormous size of the shocks, we should not be surprised.[2]

No political leader wants to say policy cannot do much in the short term to address problems that reduce economic well-being for many of their constituents, but that may be the unfortunate reality. The IRA has virtually nothing to do with the economic disruptions driving current inflation.

That said, there is a more subtle aspect of the IRA that may have a significant effect on long-term inflation over the coming decades. Servaas Storm (2022, section 11) argues persuasively that economic disruptions required to shift the world economy away from unsustainable production of greenhouse gas emissions will lead to higher long-term inflation. The logic of this argument is a slow-motion version of what I have described here for the pandemic and the Ukraine war. Fundamental restructuring of the sources of energy needed for production and consumption will put pressure on supply chains and possibly cause large shifts in relative prices, especially if these adjustments are induced by the chaos of climate catastrophes. And chaotic adjustments of relative prices will almost surely be inflationary. To the extent the IRA helps create a better, smoother path toward a climate-friendly economy, it could lead to lower long-term inflation through channels not included in conventional macroeconomic models.

Over the next few decades, perhaps the IRA really is an “inflation reduction act” because over shorter horizons it really is a climate bill.

Reference

Storm, Servaas (2022): “Inflation in the Time of Corona and War,” Institute for New Economic Thinking working paper 185, June 2022, https://www.ineteconomics.org/research/research-papers/inflation-in-the-time-of-corona-and-war

Notes

[1] Analysis from the Penn-Wharton model forecasts that the inflation impact of the IRA “is statistically indistinguishable from zero” (https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2022/7/29/inflation-reduction-act-preliminary-estimates ). The Congressional Budget Office predicts “negligible” effects of the IRA on inflation in 2022 and 2023 (https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-08/58357-Graham.pdf ).

[2] In a remarkable, extensive study, Storm (2022) analyzes the recent dynamics of U.S. inflation.