The topic of government job guarantees has generated increased discussion since the 2016 presidential campaign. More recently, a number of policymakers—especially 2020 election hopefuls Bernie Sanders, Cory Booker, Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, and Kirsten Gillibrand—have endorsed the idea. A federal job guarantee means that the government would provide jobs at livable wages to all people who are willing and able to work. The jobs program would address a number of problems including involuntary unemployment, low compensation levels, and labor market discrimination.

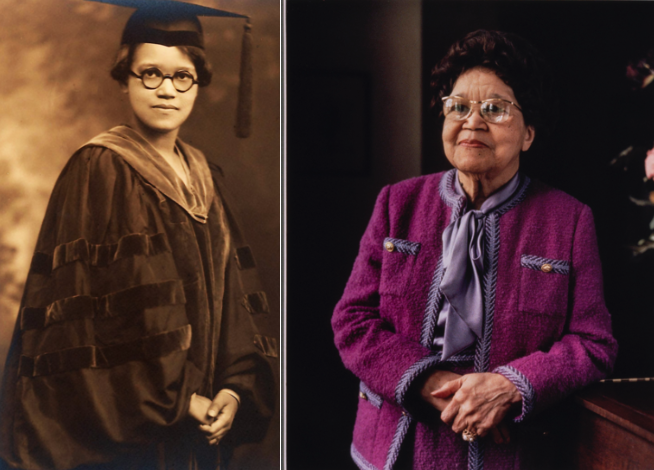

Many contemporary economists have endorsed this idea, which is often credited to Hyman Minsky in the 1960’s[1]. But, its genesis actually begins two decades earlier, with Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, America’s first black economist.

Most economists have never heard of Sadie Alexander because she was not a practicing economist, though she earned her doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania in 1921. Racial and gender discrimination denied her the opportunity to have employment as an economist, so she eventually became a lawyer.[2] I have spent much of my academic career researching Sadie Alexander’s written documents and life in order to determine if she had anything to say of interest to economists and, if so, to recover her economic analysis in order to bring her thinking into the economics profession. It turns out that Sadie Alexander had a great deal to say that is of interest and relevance to our current political economy. One area where this is evident is the renewed focus on federal job guarantees.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt espoused the idea of job guarantees in the U.S. as the nation approached the end of World War II. During the war, the government achieved full employment by having a managed economy that created jobs through public works programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). In January 1944, President Roosevelt’s State of the Union Address argued for a new set of citizens’ rights—the Second Bill of Rights.[3] Roosevelt understood that the growth of the nation into an industrial economy since the founding of the Republic required an expansion of citizens’ rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness in accordance with its economic transformation. Indeed, he believed that it was “self-evident” that “true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence.[4] Roosevelt listed the right to a job as the first right enumerated in his Second Bill of Rights and stated that the nation must move to implement these rights once the war was won.

In March 1945, a year after President Roosevelt delivered his State of the Union Address, Sadie Alexander gave a speech at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College that endorsed the idea of full employment.[5] Seemingly, the speech—given in honor of Mary McLeod Bethune—was organized around the topic of black women’s role in the postwar southern economy, women whom Alexander described as “many of the most capable leaders and thinkers of this nation”.[6] Instead, Alexander used the opportunity to analyze the overall status of black workers and to provide an argument for government assurance of full employment.

Although Roosevelt stated the right of all workers to economic security regardless of race, Alexander’s speech gave a more in depth analysis of the racial implications of economic insecurity. Both Roosevelt and Alexander believed that economic insecurity posed a danger to democratic rule at home and both wished to avoid returning to what Roosevelt referred to as “the so-called ‘normalcy’ of the 1920’s” with its “rightist reaction” to insecurity in the nation.[7] Alexander took Roosevelt’s plan for a fully employed labor force a step further by providing specific policy recommendations for implementing and financing it.

Alexander, ever concerned with racial inequality, noted that World War II led to a 100% increase in the number of black workers in war-related industries, from half a million in 1942 to a million workers in 1945.[8] Whereas 7.3% of workers in munition industries were black, only 5.7% of workers in those munition industries that would convert their production to consumer durables in the post-war period were black.[9] Revealingly, although black employment in these other munition industries increased during the war, Alexander believed that it provided an unacceptable benchmark since black employment rates were below the level attained in munitions.[10]

The War Production Board’s projection that there would be a cutback of 40% of jobs in munitions industries once Germany was defeated dimmed the prospect for maintaining high levels of black employment once the war ended.[11] Alexander argued that there were factors unique to the experience of black workers that would make them disproportionately likely to be the first workers to lose jobs: their lack of seniority[12] in munitions industries, and racial discrimination by employers in making lay-offs.[13] Alexander also stated that the prospects for black employment in other (non-munitions) manufacturing jobs were bleak once the war ended given these firms’ low percentage of black employees before the war and their ongoing reluctance to hire black workers even with the urgency of war.

Racial discrimination against black workers relegated them to the status of “marginal workers” who were the last hired and the first to be fired. As such, Alexander knew that black workers would especially benefit from full employment policies in the post-war economy:

Anything short of full employment, the marginal worker is pressing the brick on the streets [looking for work] which creates fear in fellow workers and racial friction and the Negro will continue to be the marginal worker so long as he has less seniority than other workers. Full employment would mean for the Negro worker continuing occupational advancement, increased seniority and the removal of fears of economic rivalry on the part of his fellow white workers. Full Employment is the only solution to the economic subjugation of the Negro, and of the great masses of white labor.[14]

Although focused on the particular benefits to black workers, Alexander’s speech made clear that all workers should recognize that full employment would increase their collective bargaining strength and elevate their purchasing power. This could not occur if whites continued to exclude black workers from the right to work:

When labor, white or black, native or foreign born, understands that full employment means greater purchasing power for all people, which can be obtained only by giving every man capable of holding a job the right to work, labor will have solved its own problems…. The right to work is not a black, nor a white problem but a human problem…. The more men and women who are working, the greater is the demand for goods and the more money is invested to build factories to produce goods to satisfy the demands of workers. Every man should be concerned that every other man is employed, for only in full employment is the individual laborer assured a job.[15]

In this quote, Alexander reasoned that it was in the best interest of laborers to support all workers’ rights to jobs since increased levels of employment would lead to more demand for goods and therefore generate more output and higher levels of employment. Full employment, therefore, would have the effect of providing increased purchasing power as well as job security. Alexander believed that the right to have a job was essential to the health of the nation, saying, “…. I need not state to you that full employment for all willing and able to work is also the solution to all over national difficulties”.[16]

The prospect that economic insecurity and a diminished standard of living would reemerge after the end of World War II was especially concerning to Sadie Alexander. Economic uncertainty over the loss of jobs following World War I led to race riots in 1919 and Alexander wondered about the prospects for workers after the end of the Second World War. In 1919, angry whites attacked black individuals and communities in over 25 race riots across the country, particularly in response to perceptions of black mobility. Alexander also believed that the inequitable distribution of national income in the post-war period of the Coolidge presidency helped to bring about the Depression. Employers did not pass on the benefits of increased productive efficiency to workers in the form of higher wages and lowered prices. Instead, they held onto their profits. Alexander argued that the decreased demand for goods eventually led to widespread unemployment and economic depression. The inequitable distribution of income hindered purchasing power because “the masses had no income to purchase goods and the investors refused to place their income and capital in industry because there was no one with money to buy the products”.[17]

Given the lessons of the earlier post-war period, Alexander favored government taking an active role in the economy when there were shortfalls in production. She anticipated that unemployment would be temporary in the next post-war period if government took actions to ensure that there was adequate purchasing power during the period when industries reconverted to their prewar uses. In order to have a fully employed labor force with 60 million jobs in the post-war period, Alexander believed that the country should study the factors that generated wartime full employment, going from 45 million to 55 million workers from 1939-1945.[18] The factors she believed created the 10 million additional jobs were the: 1) pressing need for goods, 2) availability of resources for production, 3) determination to use all available resources, and 4) government planning and controls on prices and labor supply.[19]

These factors were redistributive and made use of all available resources. Alexander thought that the fourth factor was necessary in order to create mass purchasing power based on an equitable taxation policy. The government would put revenue from excess profits into use for public works programs that focused on pressing needs to: “clear slums, provide electricity to every farm and reduce illiteracy”.[20] Alexander also cited the need for other policies that would increase workers’ standard of living, including a guaranteed minimum annual wage tied to the cost of living.

Three-quarters of a century ago, Sadie Alexander promoted full employment as the solution to the overall problem of economic insecurity and as the means for countering persistent racial discrimination in labor markets. She envisioned that full employment policies would ameliorate many of the economic problems that continue to plague workers in the U.S.: income inequality, marginal work, inadequate wages and the racial anxieties and disparities these problems exacerbate. Alexander stated this most eloquently in her plea for the guarantee of all citizens to freedom from want and fear: “I hold it the obligation of every American to remove those inequities which have crept into our national life and caused men to fear want and to fear each other”.[21]

The idea that the federal government should guarantee jobs paying livable wages to workers who are willing and able to work but who are unable to do so because of the failure of the private sector to provide adequate jobs is not radical. It is an idea that recognizes the corrosive nature of economic insecurity in our communities and the benefits of shared prosperity. Federal job guarantees is an idea that should appeal to people on both the left and right since it affirms the dignity of work, the freedom from deprivation, and the right of all people to contribute to the economy through meaningful production.

[1] Minsky, H.P. (1965), The Role of Employment Policy, in M.S. Gordon (ed.), Poverty in America, San Francisco, CA: Chandler Publishing Company.

[2] Malveaux, J. (1991) “Missed Opportunity: Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander and the Economics Profession,” American Economic Review 81(2): 307-310.

[3] President Roosevelt, State of the Union Address, January 11, 1944. https://fdrlibrary.org/address-text

[4] Roosevelt (1944).

[5] Alexander, S.T.M. (1945) “The Role of Negro Woman in the Economic Life of the Postwar South,” Speech given at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College in honor of Mary McLeod Bethune. STMA, Box 71 FF80. University of Pennsylvania Archives.

[6] African American women have long been active in leadership roles within the black community. The current calls to “Trust Black Women” and “Follow Black Women” in the wake of recent politics is indicative of black women’s political acumen.

[7] Roosevelt (1944). For a discussion of Alexander’s arguments about economic insecurity and racial antagonism, see Banks, N (2008) “The Black Worker, Economic Justice and the Speeches of Sadie T.M. Alexander”, Review of Social Economy 66(2):139-161.

[8] Alexander (1945), p. 3.

[9] Ibid, p. 4.

[10] Alexander’s assessment is similar to statements made recently by economist Janelle Jones in response to discussions over the lowered black unemployment during the Trump Administration. Jones was quoted in Vox, as saying, ““We don’t get to set a very low bar for economic success for black workers and then applaud ourselves when we reach it.” https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/1/18/16902390/trump-black-unemployment-rate-record-decline

[11] Alexander (1945), p. 4.

[12] Black workers had less seniority in munitions industries because they were the last to be hired, indicating that racial discrimination also affected seniority levels.

[13] Alexander (1945), p. 5.

[14] Ibid, pp 16-17.

[15] Ibid, pp. 6-7.

[16] Ibid, p. 7.

[17] Ibid, p. 15.

[18] Ibid, pp. 12-13.

[19] Ibid, p. 13.

[20] Ibid, p. 15.

[21] Ibid, p. 9.