In her new book “Naked Feminism,” Victoria Bateman explains how economic conditions drive restrictions on women’s bodily freedom and why that freedom is critical to economic prosperity.

Economist and feminist Victoria Bateman is a fellow in economics at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. Sometimes she gets asked what feminism and economics have in common. Her response? Not nearly enough.

Bateman, a long-time critic of contemporary economics, challenges her colleagues to overcome a blind spot she believes distorts the understanding of how economies prosper: namely, the status and freedom of women. Bateman, a specialist in economic history, holds that this freedom, particularly bodily autonomy, determines which societies pull ahead economically and which ones stagnate and weaken. In her book, The Sex Factor: How Women Made the West Rich, she argues that it was women’s relative freedom in the West that allowed it to flourish.

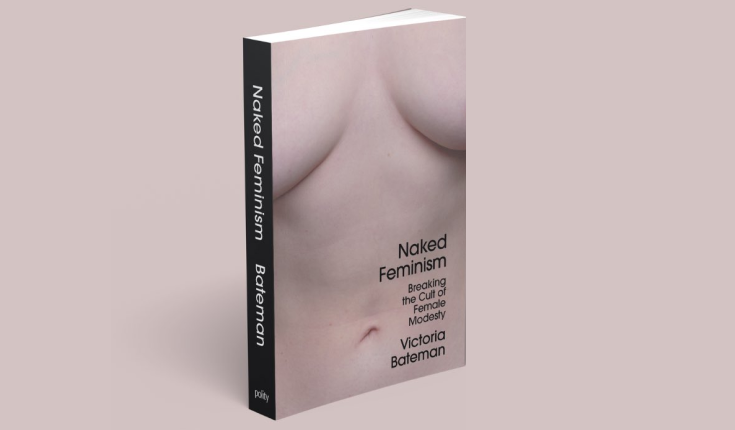

In her new book, Naked Feminism: The Cult of Female Modesty, Bateman describes how changes in economic conditions, such as rising inequality, drive crackdowns on women, particularly restrictions on their bodies, a phenomenon that results from what she terms the “cult of female modesty.” Her book traces the policing and restricting of women’s bodies from the ancient world to the rise of Christianity, Islam, and Confucianism and all the way to the 21st century, a time when, she argues, economic changes like inequality are once again producing a return to Puritanical attitudes and female disempowerment. The modesty cult, she argues, hurts not only women but whole economies.

Bateman is so passionate about confronting the modesty cult that she places her own body front and center – frequently lecturing and discussing her work unclothed, as she did for the following interview. She spoke to the Institute of New Economic Thinking about why women’s bodies matter to economics and outlines how to confront a rising tide of Puritanism, one encouraged, she holds, not only by conservatives and religious leaders but by feminists themselves.

Lynn Parramore: Can you talk about why, as an economist, you focus on the topic of modesty culture? Are you challenging what the field of economics is supposed to encompass?

Victoria Bateman: My last book, The Sex Factor, showed that women’s freedom, economic opportunity, and economic participation are vital to prosperity. I argue that historically, the West not only caught up with, but overtook the Middle East, India and Pakistan, and China – places that had been at the top of the global economic leadership table for millennia – because women had relatively greater freedom to participate in the economy, to engage in paid work.

For example, we can measure the fact that women in Britain in the 1500s, 1600s, and 1700s typically didn’t get married until their mid-twenties, and this was later than they were getting married in places like the Middle East. They were out working, earning an independent living. I draw attention to the economic role of women in the rise of the West and the role they play in creating more prosperous economies.

This work left me with a question: Why do so many countries today actively restrict women’s economic participation even though it’s bad for women and bad for their economies? Why is it, for example, that Afghanistan is pulling girls out of school and women out of workplaces? This isn’t going to help reduce poverty at the family level or help the economy and its finances. In Iran, why are women who don’t cover their hair barred from education? How do we explain so many sexist practices — virginity testing, compulsory hijab, honor killings, female genital mutilation, revenge porn, child marriage? I argue that the cult of female modesty is at the root, and it’s something as economists that we haven’t really faced up to, in part because for economists, gender has been missing for a long time. Sex and sexuality are still such a taboo.

When you look at international economic agencies like the UN studying girls’ schooling and child marriage in poorer parts of the world, things like virginity, purity, modesty just don’t feature in their reports. Yet when you talk to people on the ground, it’s obvious that concerns about the “reputation” of teenage girls drive parents to pull them out of school at puberty and encourage them into child marriages because that’s better than having them mixing with boys and risking ending up pregnant outside of marriage. Economics hasn’t confronted the very thing that’s responsible for so many restrictions on women’s freedom and opportunity: the cult of female modesty.

LP: How do you define the cult of female modesty?

VB: It centers on the question: how do we value women? What drives their worth, the esteem in which we hold them? I argue that within the context of the cult of female modesty, a woman’s worth, respect, and value depend on her body modesty – roughly defined as the degree to which her body has been seen or touched.

At the root of this is the division of women into two camps, the good girls and the harlots, or today, we might say the “brains” (the good girls) and the “bodies” (those we see as pieces of meat, the bad girls). Those in the second camp are seen as doing damage to themselves and lessening their own worth by, for example, showing off their bodies or having lots of sex or even selling their bodies as glamour models or sex workers. They’re also seen as doing damage to other women by causing men to view women in general as sex objects. They are held responsible for sexism and social problems — all kinds of problems, really, from family breakdown to disease and earthquakes to the decline of civilization. Immodest women were actually blamed for the fall of the Roman empire!

In some countries, the cult of female modesty is pretty clear, like Egypt, Morocco, and Palestine, where 80% of men agree that their worth as men depends on how their female relatives dress and behave in a sexual sense. Then there are other countries, like the U.K. and the U.S., where it seems to go under the radar. We think of our countries as being in the grips of “raunch culture” with lots of women showing off their bodies or sleeping around. But underneath this is the legacy of the cult of female modesty, which I argue is growing. A return to modesty is seen as an antidote to raunch culture, and some feminists see it as the antidote to sexism. If only women like me stop parading around naked and had more respect for ourselves, then women in the economics profession could – apparently - be treated with more respect, or women in society could be treated with more respect. This attitude victim-blames, ultimately. It makes women and women’s bodies the problem.

As women, we have come a very long way in the past few centuries in terms of our ability to do what we want with our brains, but the same can’t be said in terms of our freedom to do what we want with our bodies. A United Nations Population Fund report “My Body Is My Own” recently concluded that only one in two of the world’s women have what we would call bodily autonomy. One in two lack freedom to make their own decisions about their body — things like birth control, abortion, and so on. We’ve begun to set free women’s minds but we still don’t have freedom over our bodies.

LP: You hold that freedom of mind and freedom of body can’t be separated.

VB: Yes. Unless you’ve got body freedom – which means breaking the cult of female modesty - you can’t actually have freedom over your mind. It affects your ability to access schooling, to access work. So it’s the final frontier.

LP: How did the bodily modesty of women become an economic asset?

VB: It comes down to property rights. The cult of female modesty hasn’t existed throughout the whole of human history. Up to about 4,000 years ago, women’s sexuality, reproduction, and fertility weren’t restricted in the ways we’re talking about. The cult of female modesty started to descend around that time you get private property, and with it the development of assets and inequality. Once you have private property and the idea of ownership, inheritance becomes important. You want to pass your property on to your own children. Paternity uncertainty becomes a real worry, the fear of passing on the family’s inheritance to someone else’s offspring. You begin to focus on guaranteeing the bodily purity of your daughters, on displaying or signaling that they aren’t promiscuous and so will be faithful wives.

Effectively, you have competition among families for the richest husbands. This is going to be worst where inequality is greatest. As families compete for daughters to marry the richest men, you see the development of purity-related practices like female genital mutilation (FGM) — sewing girls up until marriage so that they can’t be married already impregnated by some other man. You get foot binding in China, virginity testing, and other practices that aim to signal that your daughter will be a pure vessel through which her husband’s family’s property can be passed down.

Where you have higher wealth inequality, the competition becomes more intense for the richest families in terms of the marriage market. And where there are high levels of gender inequality, the practices flourish because girls lacking economic opportunity can only secure themselves financially by becoming dependent on a man, by marrying and offering their body as a vessel for passing down wealth. So it’s where you have not just private property, but where it creates high levels of inequality, both in terms of wealth inequality and gender inequality, the modesty cult grows.

Often we think of things like virginity testing, FGM, and foot binding as being patriarchal things, but it’s interesting how many women are involved in them. Mothers ensure that their daughters are cut or their feet are broken or that they are veiled. It raises the question of whether women collectively work a bit like an OPEC organization to restrict the supply of women’s bodies and restrict the supply of sex because in a society with high levels of gender inequality, where women are basically just reproductive vessels, by restricting supply you can increase the price or the reward that women can get from their bodies or from sex. For example, husbands may treat their wives better if they can’t access sex elsewhere (e.g. if unmarried women are kept away from men and sex workers are absent). In societies with high levels of gender inequality, perhaps women act collectively to encourage each other to cover up, to adopt practices that protect their daughters’ reputations because ultimately their survival depends on it.

The modesty cult started around 4,000 years ago in the Middle East and Eastern Mediterranean, but it has fluctuated a lot over time. Three things seem to create upswings: rising inequality, rising population pressure, and rising warfare.

If you look back at medieval Europe, things were a bit more liberal – these were the days of Chaucer and pilgrims collecting badges with genitalia on them. Europe had seen population collapse with the Black Death, along with a redistribution of income as land owned by the rich became worthless and wages for labor went up. As population pressure went down, inequality went down and the modesty cult recedes. But by the 1600s, the population was almost back to where it was before the Black Death, and inequality begins to rise again. Soon the Puritans are on the march. They then returned in the Victorian Age, which was a time of economic growth with the Industrial Revolution, but at the same time, you’ve got rising population pressure in the form of a massive population boom, and rising inequality. In the 20th century, you’ve got the Pill, falling population pressure, and government trying to do something about inequality, the welfare state, and so on. Population pressure recedes and inequality recedes, and so does modesty culture. But now in the 21st century, inequality is going back up, and with it, the modesty culture is coming back.

We’re seeing the way culture affects the economy and the economy affects culture. As economists, we haven’t been very good at thinking about this.

LP: How can we understand a practice like honor killing, the murder of a woman for a perceived immodest act, in an economic context?

VB: Economic opportunities - the ability to go out to work, earn money and purchase what you need on the marketplace - can help women at an individual level to escape the modesty cult. But a woman’s family may still be dependent on her reputation for modesty, even if her own life has become less restricted by it through access to economic opportunity.

Where a family’s survival depends on social networks, and participation in those networks depends on the family’s reputation, transgressions by female members of kin (such as by leaving home and working alongside men, leading others to “gossip”) can have serious ramifications: your father’s job could be at stake; customers may no longer wish to buy from your family’s market stall; richer members of your clan or caste may no longer wish to lend to you; and the sons of promising families may no longer wish to marry your sisters. Honor killings are, therefore, commonly used to punish women and in turn to maintain the broader family’s reputation, and, with it, their economic survival.

LP: How do you see what is happening in the U.S. in terms of the modesty cult?

VB: Within Evangelical Christian communities, you’ve seen a rise in female modesty culture with things like virginity pledges, chastity balls, and a real fear that “harlotry” is leading to the relative decline of American civilization – that badly-behaved women are the reason America is losing its grip globally and economically. So you have attempts to clamp down, to restrict women’s ability to control their own fertility with a view that if you deny them access to an abortion — and ultimately where is this heading, access to birth control – they will behave better, turn away from “harlotry”, with social breakdown and relative economic decline being stopped in their tracks.

Not only do you have religious zealots and conservatives adopting this view, but increasingly feminists as well. Wendy Shalit’s book, A Return to Modesty, was a big seller in the U.S., arguing that if we want to bring sexism to an end then it would help if we became more modest, if we respected our own bodies more. Ariel Levy’s Female Chauvinists Pigs takes a dig at raunch culture and argues that strippers and celebrities who flaunt their bodies are standing in the way of addressing sexism. More recently there’s Bernadette Barton’s The Pornification of America: How Raunch Culture is Ruining Our Society. Feminist writing like this views a return to modesty as a way to solve gender inequality and achieve more respect for women in the workplace and out in public, and better lives for women as a result.

With all this in mind, in America, there is an increasing demonization of women who reveal or monetize their bodies, like strippers, glamour models, and sex workers. But why shouldn’t women who monetize their bodies have the same rights and respect as women who monetize their brains in the economy? There’s a lot of morality that gets in the way of achieving that. You’re seeing women in adult entertainment having their bank accounts closed down or being denied access to credit cards – the type of financial exclusion that is seriously impacting women who are simply trying to make a living.

LP: In the book you point out that it wasn’t so long ago that women making money through acting or singing were looked down upon, seen as immodest.

VB: Yes, female singers and actresses have in the past been considered tantamount to sex workers. The seventeenth-century Puritans, amongst others, clamped down on them. But the pendulum of female modesty swings, and in the eighteenth century, women actually had quite a lot of freedom. During the Georgian era, it was normal for women to be out there working, earning a living, including in the artistic sphere. Women had a big readership in the book market, so there were many famous novelists from the time, like Frances Burney, one of Virginia Woolf’s favorite novelists. It was a more liberal time. The symbol of the French Revolution was actually a topless woman! Women could take to the barricades topless and fight for revolution. Mary Wollstonecraft was part of the French Revolution and became pregnant outside of marriage, writing her own books critiquing women’s bodily “purity.”

With the Industrial Revolution, things started to take a negative turn for women. There was a return of the Puritans and an obsession with saving women from harlotry. By the middle of the 19th century, almost half of the charitable institutions in London aimed to rescue fallen women. The original Suffragettes argued that for women to make progress, politically and economically, we need to be respectable. The colors of the Suffragettes were purple, green, and white, with the white symbolizing bodily purity. Their idea was that if we can prove ourselves more chaste, more respectable on a bodily level than men who are being promiscuous and sleeping with prostitutes, then we will be listened to and get better treatment. I think it was a big mistake to build freedom on women having to pass a modesty test, on the idea that women have to be respectable in terms of their bodies in order to be given the same rights as men.

It was only in the twentieth century that feminism started breaking away from this purity culture by supporting things like birth control and abortion. The Suffragettes were very anti-abortion, anti-birth control. But today, there is a return to that type of illiberal, Puritanical feminism which I find worrying, with feminists demonizing “immodest” women. Perhaps it’s quite natural that the pendulum will swing between periods when we’re much more liberal about women’s bodies and sexuality and periods when we think it’s gone too far and we need to crack down. But we tend to forget how bad the past was. We look at the good sides of the Puritanical ages, when women seemed to “look” respectable, and we forget about things like the demonization of sex workers and the literal flogging of single moms.

LP: What do you see as effective ways to challenge the modesty cult today?

VB: Three steps. The first one is to look inside ourselves. Many of us have been brought up explicitly or implicitly within this cult of female modesty. If ever we have been called a whore or used the word “whore” or any of its many variants, then we’ve been part of it. If ever we’ve worried about our reputation, if ever we’ve worried about how we dress to go to a conference, to the office, if we’ve been a victim of revenge porn — there are so many aspects of our lives that have been touched by modesty culture and it’s very easy to internalize it. So part of it is questioning the way we judge ourselves and other women. Certainly, in my case, it took a very long time to break free of the cult of female modesty.

The second thing is to challenge whorephobia within feminism, collectively, as a group. If you’re looking at feminist writing that argues that sex workers need to be wiped off the face of the Earth, or that scantily clad women are responsible for sexism, then we need to call that out and understand that what we should be aiming for is a world in which all women have rights and respect, not just those of us that behave modestly. If we are demanding freedom for our brains, we also need freedom for our bodies. The same rights for women who monetize their bodies as those that monetize their brains. That won’t occur unless we break the modesty cult.

Finally, if we’re going to crush this Puritanism within feminism, then we need to replace it with something else. I believe there is a lot further to go with the idea of “My Body, My Choice.” We can broaden the concept to include not just abortion, but the rights of all women to do what they want with their own bodies. That requires tolerance because we’re going to make different decisions from one another. More generally, whether we’re in the playground, in the office, or out on a Saturday night, we need to call out anyone who uses “whore” as a term of insult. We need to challenge anyone who is judging women on the basis of their bodily modesty when there are much more important things in life, like how kind and generous you are, or your achievements.

Ultimately, a woman’s worth should not be based on something as superficial as what she is wearing or whether her hymen is intact. All women deserve respect – not just those who pass a modesty test.