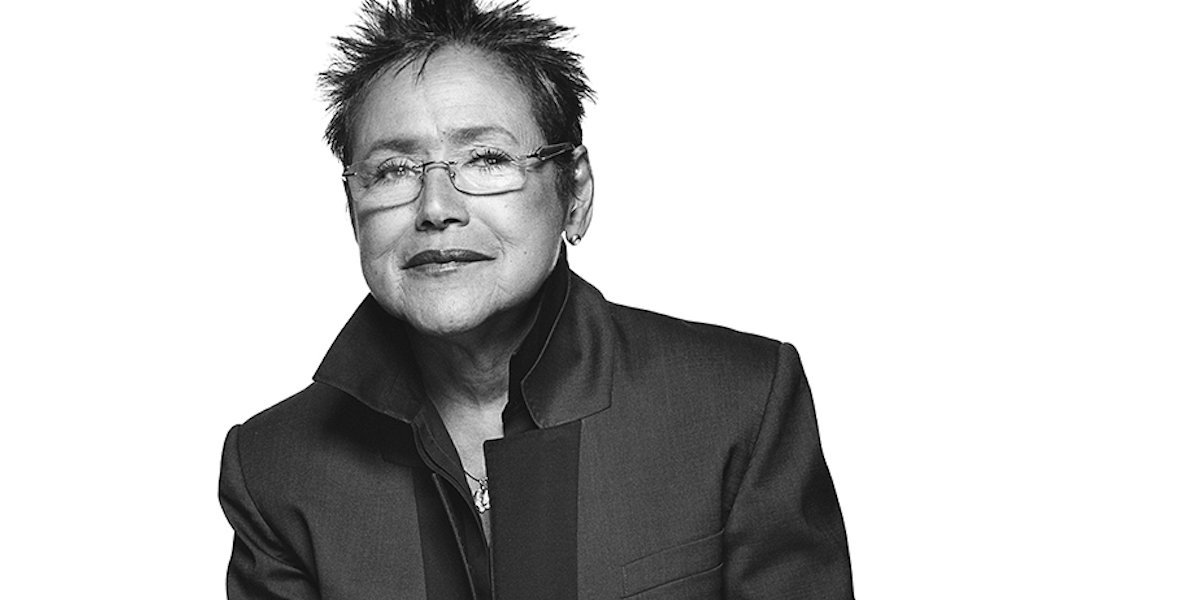

The activist and author shares a free-ranging conversation with INET president Rob Johnson.

Elaine Brown, prison activist, writer, singer, and former chair of the Black Panther Party, has spent a lifetime taking on America’s oppressive systems of racism, capitalism, and sexism with fierceness and clarity. She recently joined Rob Johnson, president of the Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET), in a free-ranging podcast covering America’s current racial reckoning, her social justice work in Oakland, California, and what can and cannot help us navigate these turbulent times. You are urged to listen to part 1 and part 2 [to come soon] of the complete 2-hour discussion – if you dare.

I say “dare” because Brown’s words do not soothe. She offers no succor to white people, the affluent, or those who support the status quo. She has no time for panaceas or pablum, and she won’t be sidestepping anything that might offend you. Her jam is tear-it-out-by-the-roots transformation, not tweaks and weak reforms.

But if you are prepared to reconsider your assumptions and to refocus the lens through which you view America’s social and economic landscape, then buckle up. Brown offers a jolting, but invigorating ride.

In her 1992 memoir A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story and in public talks, Brown describes growing up in a rough North Philadelphia household dominated by strong black women determined to see her educated. Moving between a predominantly white school for gifted students and hanging out with poor neighborhood kids gave her a deep sense of the country’s racial and economic disparities. Later, after studying at the Philadelphia Conservatory of Music, where she wrote her first songs, and a brief stint at Temple University, she moved to Los Angeles where she encountered radical Black Power politics.

Eventually she joined the Black Panther Party, rising through its ranks so successfully that when Party co-founder Huey Newton fled to Cuba to escape murder charges in 1974, he appointed Brown to lead the organization in his absence. She is the only woman ever to hold the position.

How did a black woman from a poor background wield this kind of power in America? Not by being nice. In her memoir she writes of how when she took charge of the Panthers, she notified a gathering in Oakland that she would brook no opposition: “I have all the guns and all the money. I can withstand challenge from without and within… Together we’re going to take this city. We will make it a base of revolution.” The tough talk was paired with community-building programs that provided housing and free health clinics, as well as the successful election of the first black mayor of Oakland.

Since parting ways from the Panthers in 1977, Brown has focused on issues including the criminalization of poverty, mass incarceration, and the concrete needs of oppressed communities, such as her work as CEO of Oakland & the World Enterprises, which provides support for formerly incarcerated people and others barred from economic opportunities to build businesses and become self-sufficient.

Brown’s life and work have given her a powerful framework for analyzing the current moment. In her conversation with Johnson she observes that the pandemic has simply served to expose the reality of a country that has institutionalized the oppression of black people and people of every other color, including whites, who happen to be poor. While she finds hope in the rage triggered by George Floyd’s murder and is “glad to see people are at least awake, if not necessarily conscious of what needs to be done,” she warns that you can’t dismantle a “400- year institution or empire with a protest in the street.”

Brown is unimpressed by the “very minor” reforms some are asking for in the face of police brutality and economic inequality when what is required are “fundamental” and “revolutionary” changes – the kind of transformation sought not only by the Black Panthers, but also, she points out, by Martin Luther King, Jr., who, before his murder, was about to embark on a campaign for poor people to address the structural oppressions of a country that needed to be “born again” in the sense of being totally “uprooted and reorganized.”

Asking your oppressor to please stop what they are doing, she says, is not going to cut it.

“Just ask a banker’s big corporations to redistribute their wealth and to think that’s really going to happen by simply marching in the street and annoying people again…to imagine that that is a pathway to dismantling the system in place that put that cop’s knee on George Floyd’s neck is to not have a correct analysis, but I’m happy to see that the spirit of some sort of opposition is finally reappearing.”

Tension between law enforcement and the black community nothing new to Brown, who faced the lethal threat of police violence as a Black Panther. She notes a similarity between today’s young people and those she recalls in the ‘60s who were not interested in appearing respectable when confronted with brutality: “We’re in your face, and we’re angry and we have a right to be angry.” The current movement, she notes, can learn from the past:

“I think there are some lessons that Black Lives Matter has taken from the Panthers—some cautionary tales. There’s a tendency in the Black Lives Matter movement to be less centralized, to be a leaderless movement. Some of that might be as a result of what was one of the great downfalls of the Panthers. Once your leaders get corrupted one way or another, it’s hard to stop the organization from being corrupted.”

Brown is glad to see action ignited, but she knows that this does not necessarily mean that change is going to come. She has been around long enough to be skeptical of easy answers:

“It has the potential for change only if it comes to be developed into an organized force that is going to start the long, hard march of dismantling, trying to dismantle, those institutions that have kept black people oppressed since the beginning of this country in Jamestown.”

She observes that the prison system is just one more arm of all the other aspects of profiteering that the country lives on. The takeaway is that in its current form, America runs on oppression. So, it can’t continue in its current form.

Instead of offering up easy answers, Brown prods us with probing questions.

What does it mean to have police reforms when police exist to protect and serve the institutions that keep us oppressed?

What does it take for America to decide to put money into keeping children and human beings healthy, as other countries have decided?

Why do American schools remain defunded and segregated, well over fifty years past Brown v. Board of Education?

Do we want to deal with these things, or don’t we? Why are we crying? Why aren’t we fighting?

Brown, always attuned to music, recalls the song “Wake Up, Everybody,” sung by Teddy Pendergrass with Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes in 1975. The lyrics resonate with the message of a woman who knows how to fight the long game:

“The world won’t get no better, if we just let it be.”