The need to understand China is obvious, but how to go about it? The lack of Chinese philosophy education in the U.S. presents a serious challenge, compounded by daunting barriers of language, stark cultural contrasts, and disparities in worldview. Concepts may not align neatly with Western philosophical frameworks, requiring a subtle understanding to grasp fully or even perceive the differences.

Anyone who sets out to comprehend China’s complexity confronts an intricate tapestry woven with threads of continuity, bursts of disruption, and variegated patterns. China’s history is filled with paradoxes, merging timeless traditions with the dynamism of transformation. From ancient cultural legacies to the ebb and flow of centralized governance over two millennia, China embodies a profound reverence for its heritage. Yet invasions, dynastic shifts, and revolutions have continually reshaped China’s socio-political and intellectual landscape, showcasing its adaptability. This invites exploration of the interplay between tradition and innovation, enriching our understanding of Western and Chinese thought.

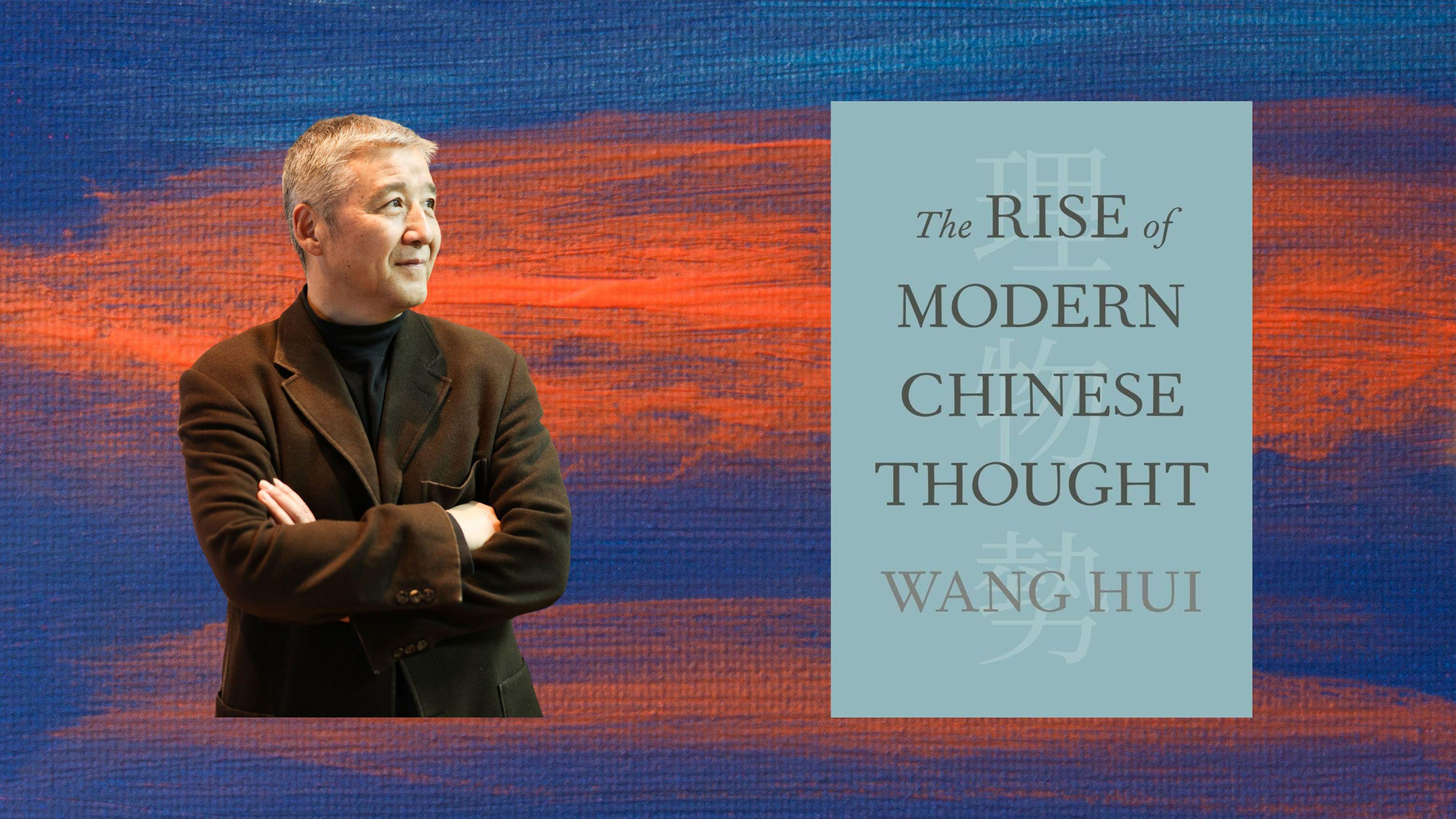

If you’re ready to set forth, the contributions of Wang Hui, one of China’s most prominent intellectuals, are indispensable. After twenty years, English speakers can finally access his magisterial The Rise of Modern Chinese Thought, which provides a comprehensive exploration of China’s intellectual traditions, emphasizing their diversity and interconnectedness. Avoiding teleological narratives, he traces developments in Chinese thinking from antiquity to the present, highlighting key philosophical movements and their impact on Chinese society and governance. Wang argues for a contextual understanding of Chinese thought, viewing it as a dynamic dialogue between tradition and innovation, shaping China’s cultural identity and its interactions with the world.

In exploring China’s intellectual development, it’s essential to pause and delve deeply into the Song Dynasty (960 to 1279 C.E.), a transformative period that continues to shape modern ideology and governance. Wang illustrates how this era witnessed the shift from barter to a currency-based economy, the consolidation of centralized state power, the decline of the aristocracy, and the rise of the gentry-bureaucratic class. Additionally, it saw the emergence of egalitarianism, urbanization, and a Renaissance-like dissemination of knowledge, alongside a philosophical shift towards Neo-Confucianism from Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism. This significant social and economic development profoundly influenced China’s intellectual and political landscape, extending its impact well into the twentieth century.

Neo-Confucian scholars of this period saw public service as paramount, drawing inspiration from China’s revered Sage Kings, who provided guiding principles for conduct, governance, and social harmony, the foundation of what is known as the “rites and music” tradition. This tradition, extending beyond rituals, encompassed broader social and political dimensions. Wang explains how the School of Principle, a dominant Neo-Confucian movement in the Song Dynasty, influenced governance, education, and social beliefs. Emphasizing moral cultivation and self-reflection, this school advocated for a “Heavenly Principle” worldview, aligning morality and governance with universal harmony. Wang emphasizes the role of Song Confucians in shaping the domain of intellectual discourse, advocating for a return to tradition while simultaneously critiquing contemporary practices.

In the following conversation, Wang unpacks why he emphasizes specific conceptual frameworks in his historical analyses. He argues that Chinese concepts like principle (li), things (wu), and the propensity of times (shi) are vital for understanding the development of Chinese thought. Wang explores how these concepts reveal a tension between established theoretical paradigms and the complex nature of historical phenomena. He illustrates how Song Confucianism’s focus on concepts like li signifies a critical engagement with contemporary social, political, and moral systems, rather than a blind adherence to tradition. This critical perspective allows for a reevaluation of historical narratives and the development of alternative frameworks for understanding Chinese intellectual history.

Wang’s approach challenges contemporary and historical interpretations and promotes a more nuanced understanding of historical change.

Lynn Parramore: Your book traces the development of three concepts: “principle” (li), “things” (wu), and the “propensity of the times” (shi). What makes these crucial to understanding the progress of Chinese thought?

Wang Hui: Why these very specific concepts? I employed these concepts as clues to describe historical change, rather than employing social history, cultural history, economic history, or military history. I wanted to use these concepts to link different things together. Basically, I think that in all of Chinese studies — and not only Chinese studies, but historical studies, generally, especially in non-Western cultures — two prevalent misgivings have often left scholars feeling frustrated.

First, they struggle with whether or not they can effectively use existing theoretical categories or social scientific paradigms to describe and interpret historical phenomena. For example, if we talk about the traditional Chinese wellfield system [an agrarian plot division for equitable land distribution], people will often describe it as an economic system. But the wellfield system is not only an economic system, but also a social, political, and military system, and, after all, a racial system. So in that sense, once you reduce that phenomenon into the category of the economy, you’ve lost a lot of things. That’s one issue.

The second, of course, is that we are all studying Western social science — it’s a universal phenomenon – so the concepts and paradigms we deploy usually come from studies of Western history. Can they be usefully applied to non-Western historical phenomena? I have found that you always need to construct a dialogue between the different concepts.

In my book, I discuss principle (li), things (wu), and the propensity of times (shi) as philosophical ideas. These are three key categories, but at the same time, I use another set of three antithetical concepts in the more historical analysis. The first is the ancient rites and music culture and institutions. The second concerns political systems, enfeoffment [the feudal land grant system], and centralized administration. The last one was more of a response to what contemporary Western scholars are working on, and also something we’re working on in Chinese studies: the empire and the nation-state. I question these binaries and their application to Chinese studies.

LP: In Song Confucianism, “li” is seen as vital for both social harmony and moral growth, encompassing both adherence to traditional norms governing behavior as well as broader philosophical and ethical principles. Why did scholars prioritize this concept?

WH: Li was a very early, very traditional idea, and it was only in the Song dynasty, especially the Southern Song and afterward, that it occupied the highest position in Neo-Confucian thought. Some describe Song Confucianism as an archaism, a nostalgia for tradition, because before the Song dynasty, there was a Buddhist dominance, and the Neo-Confucians drew inspiration from a time before that shift.

Various early Confucians viewed rites and music and the [current] institutions as overlapping – seeing little difference between them. For them, the rites and music system, the family system, the wellfield system, and the political system are all the same, together forming the fundamental framework of behavior and encompassing moral doctrine. However, Song Confucians actually sharply divided these systems from each other. They thought that when you talk about rites and music, you’ve lost the essence. We can imagine something similar when people talk about democracy. Democracy is a framework, but a lot of people will criticize that idea and say, no, it’s not democracy — it’s lost its spirit or essence. So though the framework was still there, the Song Confucians’ division between rites and music and institutions actually came from a critical stance. It’s a paradigm shift. This is the first point.

Secondly, Song Confucians strove to reincorporate substantive elements from the time of the early Sage Kings, the Three Dynasties, back into daily life. They talk about the patriarchal clan system, which was part of the rites and music system. They tried to argue that we needed to return to the early Sage Kings’ time in considering the education system, the wellfield system (later described as an economic system), and the system of enfeoffment. However, this perspective can’t be viewed as mere archaism. It can only be comprehended in light of the Song scholars’ critical understanding of the current system, the civil service examination system, which was very different from the traditional education system. They also criticized the centralized bureaucracy in contrast to enfeoffment (the feudal system). The Song Confucians were also very critical of commercialization and social mobility because, in the rites and music culture, morality was based on a certain kind of community. They’re talking about returning to the early days, but they’re also actually trying to have a critical stance on the contemporary world.

Why do they put li at the top of the whole system? Why were they so dedicated to developing a category of li, the Heavenly Principle, and to talking about the Way of Heaven and so on? Confucius himself never paid so much attention to the abstract idea of li— what he talked about is everyday ritual practice. When the Song Confucians talk about li, they are talking about something like immanence. You still have the rites and music — the performance, the ceremony, and so on and so forth — but you can’t take these things for granted as representing the essence of the rites and the music. Now the rites and music exist in a way as the immanence. The Song Confucians went back to the rites and music, but not simply to reconstruct the rites and music. They are developing the idea of li.

LP: How does this fit into the overarching narrative of Chinese intellectual history?

WH: Is this an ontological or epistemological breakthrough? Traditional philosophers, those in the early days in America like Feng Youlan, who wrote a very famous textbook [in English], The History of Chinese Philosophy, treated this Song idea as a philosophical breakthrough. China finally had philosophy!

But really, the idea of philosophy only emerged in China in the early 20th century. The first translation of Youlan’s book was in the 1870s, mainly in Minju, Japan. They translated the Western ideas into Chinese characters. They translated the term zhexue [the study of wisdom] as philosophy. Later, overseas students who studied here had to reconsider Chinese thought. They had to use the frameworks and categories of philosophy, ontology, epistemology, realism, and so on, as well as the social sciences categories, to describe Chinese intellectual history. We need to think about this kind of relationship.

The fact that Song Confucians prioritized relatively abstract philosophical and ethical categories indicates the political thinking embedded in Neo-Confucianism because they are very critical of the current political, economic, educational, and even moral systems. They thought these systems were lost.

They are critical on the one hand, but they also recognize historical transformation. We can imagine a contemporary like John Rawls, who talked about justice, but obviously thought that the reality was unjust, and a lot of problems emerged from that. He tried to construct an abstract system to talk about the problems of redistribution and justice while still recognizing the legitimacy of democracy as a basic framework. In that sense, the Song Confucians, too, recognized historical change. They took the form of archaism, but they recognized the inevitability of historical change. We cannot simply go back to earlier years. We need to study phenomena to grasp the essence – that’s the li. The li can help us to imagine our ideas, systems, and behavior.

The inherent historical dynamics for the establishment and the deployment of the Heavenly Principle worldview were clearly set forth in the exploration of the differentiation of [ancient] rites and music culture from [current] institutions. Basically, Song Confucians saw that while moral values are not immanent in systems, they could find moral values by studying the systems. They set forth to explore the differentiation of the rites and music culture, which was the system of the Sage King, from the institutions, or current systems. They found that even the current systems exist on behalf of or within the Sage Kings’ rites and music culture.

I’ll just give an example. If you have a critical mindset, and you hear people defend the current system as a democracy, then the critical mindset will say, no, this is not a democracy. But to criticize in this way also legitimizes the value of democracy. The mindset of critical thinking that came from the Song Confucians was sort of conservative but actually very critical. They argue for this differentiation and also the comparison among the Three Dynasties (the Sage Kings’ time), and the eras that followed. The Sage Kings’ time became the ideal used to criticize contemporary reality. It’s similar to how people resort to Plato, Aristotle, the 18th-century Enlightenment, and so on to criticize current practices and reality. So you have a discussion of the dialectic binaries of centralized administration and enfeoffment; the wellfield system and the equal field system [a system to distribute land fairly among households based on their needs]; and the schooling system and the civil service examination system. In the Song Dynasty, these systems were attached to the centralized administration system and more like a proto-nation-state than what the Kyoto School [a Japanese philosophical movement blending Western and Eastern thought] argued for.

Using ideas or propositions like principle (li) to investigate things and extend knowledge was popular among Song Confucians and later Confucianism. If we simply deploy categories like li for economic, social, political, or historical narratives, we will not only reduce these complex conceptual problems to the components of these later narratives, but once we have encapsulated them as such, we will also have neglected their significance in the intellectual world of antiquity. Therefore, we need to examine these concepts within the framework of the particular worldview of that period, and then explain the phenomena that modern scholars have categorized as economic, political, military, or social in the context of their relationships with Confucian categories such as li (Heavenly Principle), and so on. We can then provide an internal perspective through this narration.

LP: How might an understanding of li aid us today?

WH: This internal perspective is a way to observe our own system. For example, when we talk about human rights, the classical idea of rights is not only a legal concept. It means doing things that are just. But this meaning was lost in modern times because you can weaponize or abuse the idea of human rights. Some people were trying to understand the classical idea of human rights, how to define them, and enrich the category of human rights. In that sense, the classical idea is not simply observing objects, but having an internal perspective for self-reflection. Historical study works in this way: we master observation, but also we are objects for reflection.

That reflection needs certain kinds of categories that construct the internal perspective to understand us. If we think about current crises, political crises, a lot of this links together. We need some perspective to understand it. We can’t understand it if we are simply stuck within it. If we are stuck within a perspective, we may find a solution that is actually the origin of the current crisis. It often happens like that. That’s why the idea of li becomes so important.

When we talk about the concept of things (wu), traditionally in Confucius’ time, wu was part of the rites and music culture. It overlaps. When you think about anything, it’s always within the system of rites and music. In that sense, wu always contains moral implications. It comprises the dynamic structure of our behavior. But if you live in a society that, from a Confucian perspective, is already in differentiation, then rites and music, even the form, have lost their substance. So wu becomes the object. You still do the rites, the ritual practice, but that ritual practice only concerns things or objects, not real moral implications. That’s why traditionally speaking, morality existed in people doing things. That’s the ritual order. But the Song Confucians emphasize that you need to start investigating things to achieve knowledge. Li is invisible within things (wu), so you need to investigate things. The idea of things themselves, when we talk about objectivity or the object, actually came out of what was not only a scientific discovery but also a historical transformation, the result of that differentiation from that perspective.

LP: And what about the propensity of times, this concept of the prevailing trends associated with a particular era, and that shapes its norms and behavior? What makes it important to Chinese thought?

WH: The concept of the propensity of times was also a very traditional idea. Mencius once asked, why is Confucius a sage? The answer: Because he knows the propensity of times. This concept is very different from the idea or the concept of time in the modern world — the linear, teleological, homogeneous, and empty concept of time. This is our time.

The propensity of the times is something else, and I try to use it as the conceptualization of history in Neo-Confucianism. I can understand why the Neo-Confucians re-employed this term to describe history. They said that there was a time before the Sage Kings’ time, the early Three Dynasties, and after. This is a periodization [a division of history into distinct periods based on significant events, developments, etc]. This is not based on the linear, teleological time. It’s based on their understanding of the propensity of times. The propensity of times in Song Confucianism became an inner matter or matter of interiority. So the li is linked together in the interior.

In that sense, the propensity of times is closely linked to what they talk about in terms of the differentiation of rites and music from institutions — in terms of historical changes. The most important thing is that when we talk about time, we actually construct the objective framework. But the propensity of times means that we are all within that propensity. We are the forces that change the propensity of times, and we are the products of the propensity of times, but we are also the active players that force the change of the propensity of times. So it’s a very dynamic term and helps to get rid of an overly teleological narrative of history. That’s why I try to compare this very specific concept of time with the modern concept of time — basically to get rid of the so-called teleological narration of history.

An example is the inquiry into Chinese modernity. The Japanese Kyoto School (1920s to 1940s) argued for the importance of Song Confucianism. One of the leading figures in the Kyoto School raised the issue of the transition from the Song Dynasty to the Tang Dynasty, and later, another figure, Miyazaki Ichisada (and some others), argued that the Song Dynasty already had a certain kind of capitalism. To define the early modern in Chinese history, they used a standard narration, such as the decline of the aristocracy leading to the maturity of a central administration that was labeled as a proto-nation-state, and the growth of long-distance trade, which means a more sophisticated division of labor. And the productivity, urbanization, and the standardization of the civil service examination system, which meant that, because of the collapse of the aristocratic system, now everybody could pass the examination system to be employed.

And that was true — before the Song dynasty, all the high-ranking officials came from the aristocratic system. However, after the Song dynasty, all the prime ministers came from the national service examination system rather than an aristocratic background. A kind of civilian society emerged from then on. So for the Kyoto School, Song Confucianism is a kind of ideology of nationalism, a proof of nationalism. They would argue for these as the starting point of the early modern era.

However, at that time and later, some Marxists argued that the later Ming Dynasty was the starting point of Chinese modernity. They raised the question, what is modern? And also, what is China? The Song, Ming, the Yuan Dynasty, and the Manchu Qing Dynasty were very different in terms of territory and ethnic composition. The systems were very different. So how to define China? And of course, how to define Chinese thought or philosophy? And then how to define the rise of Chinese thought? My book is about the rise of modern Chinese thought – and you can actually question each term itself.

If you talk about the rise in the teleological way, then when was the rise? Was it in the Song or Ming dynasty? Or was it the modern 1911 revolution? Or, like Francis Fukuyama said, did the early modern political system, and its structure, really start 2000 years ago in China in the Qin dynasty? He said that the Qin dynasty was almost like a proto-nation state. Whether or not it can be defined as early modern, that’s very strange to some extent if you really think about it in a teleological way.

So, my question: does the concept of li (Heavenly Principle) embody an antagonism, a tension between its ideas and the Song transition? First of all, I disagree with the Kyoto School when they say that Song Confucianism is proto-nationalist, expressing the ideology of nationalism. Rather, they took the form of archaism, but you cannot reduce it to an ideology. You can only legitimize the transition. They recognize it, they criticize it. There’s a contradictory or paradoxical decision there.

So why did the Kyoto School say that the Song dynasty, or even more, Song Confucianism, was nationalistic? Because they thought the Song dynasty, compared to the early dynasties, was an even more Chinese China. Confucianism was thought of as China, whereas Buddhism was a foreign idea that came from India. How, then, can we represent the Song transition from a Confucian perspective? And how should one portray the social structure in the Mongolian Yuan dynasty after the Song? Or even more to the point, the social system of the Qin dynasty, the last dynasty, the Manchu dynasty? If you argue that the Song dynasty is the more Chinese China, how to define the Mongolian China or the Manchu China?

If you start from the teleological or linear way of thinking about the modern, does that go back to ancient times or something else? It’s contradictory, because if you do that, then you’ve lost the whole narrative thread. That’s why I think that the idea of the propensity of times gives us another way of imagining history, another way to think about these kinds of things. In that sense, we can also rethink contemporary China, and go beyond the binary of empire and nation.

For example, we can talk about modern China, the Republic of China after the 1911 Revolution, as emerging based on the last dynasty, the Qing dynasty. It overlaps with the territory, the populations, and a lot of the systems. Then we need to ask the question, how did Confucianism, as well as other sources, legitimize the Qing as a Chinese dynasty though it was very different from the Ming dynasty? It had the Manchu as the ruling class, but it’s still broadly recognized as a Chinese dynasty. How is that legitimized?

Understanding historical change is very important for Confucianism as a political philosophy. It’s not only the history of ideas. It’s full of the political dynamics within the ideas. People say, well, now we are modern. Then why are you talking about Plato, Aristotle, all the ancient ideas? Because you are still trying to retrieve those ideas for the contemporary world.