Economists’ macro stories

Last December already, Paul Krugman gave his own account of how microfoundations came to be the 70s, and why they unduly spread over subsequent decades, and so did Stephen Williamson. Economists’ need to ground their methodological debates into self-made historical narratives is in itself an interesting feature for historians. But in a recent post dealing with the “Faustian bargain” New Keynesians may have sealed by endorsing of the New Classical microfoundational program, Simon Wren-Lewis asked a more direct historical question:

Is this how it happened? It is true that New Keynesian models are essentially RBC models plus sticky prices. But is this because New Keynesian economists were forced to accept the RBC structure, or did they voluntarily do so because they thought it was a good foundation on which to build?

And Noah Smith added a second one:

“are macroeconomists doomed to always ‘fight the last war’? Are they doomed to always be explaining the last problem we had, even as a completely different problem is building on the horizon?”

It thus seems the kind of narratives economic bloggers are after are of two kinds:

- Brain stories about how and why economic ideas (microfoundations, representative agents, technology-driven business cycles, calvo-pricing types of rigidities) emerged. As Bob Lucas puts it in a reminiscence on Kydland and Prescott’s Time to Build paper,”how did they ever think to put all these pieces together in just this way?” Not quite sure that the appealing “new-ideas-emerge-in-reaction-to-the-latest-economic-crisis” pattern, widely used by economists and historians alike, is an accurate representation of how macroeconomic ideas develop.

- War stories about how such ideas gained traction, spread, and eventually became the exclusive standard for academic publication, forcing their opponents into defensing positions. A possibility that Wren-Lewis entertains (an eventually rejects) it is that New Keynesians’ turn to microfoundations was a strategy “to be reintroduced into the academic mainstream.” Likewise, Krugman mentions a journal “blockade”

For once, let’s refrain from complaining again about the disregard of HET scholarship economists’ half-baked attempts at self-made/ self-serving history reveal, and let’s ask instead: do historians have any such brain and war stories to offer? And if not, is it possible and valuable at all to write such stories?

“How did they ever think to put all these pieces together in just this way?”

The recent book Microfoundations Reconsidered edited by fellow blogger Pedro Duarte and by Gilberto Lima exemplifies both historians’ ability to tell rich and complex brain stories and their failure to produce the war stories that are crucial to understand the current state of macro.

The authors’ concern is not merely to document the intellectual development of those economists usually associated with the dominant breed of microfoundations – the formal derivation of aggregate relations from the inter-temporal optimizing behavior of rationally-anticipating agents – , but more broadly to demonstrate how pervasive the question of the relationship of micro to macro had been since Ragnar Frisch coined the two terms in the 30s. Several chapters trace alternative microfoundational programs back to the 50s, when the word “microfoundations” was coined. Long before Phelps intended to “found a theory of aggregate supply” on “a new kind of microeconomics of production, labor supply, wage and price decisions” and Lucas initiated what would quickly become an “eliminative” microfoundational program – the word chosen by Kevin Hoover to emphasize the centrality of the representative agent –, the general equilibrium framework on which the “neoclassical synthesis” was built had been seen as a bridge between micro and macro and had fueled sustained discussions over the relationships of aggregate equations to individual behavior. In his opening survey of alternative “microfoundational programs,” Hoover also details Lawrence Klein’s long-standing attempts to ground the aggregate relationships of his large-scale macroeconometric models into microeconomic theory without endangering their empirical tractability. Other papers investigate how figures ranging from Marschak, Koopmans, Modigliani, Hicks, Morgenstern, Patinkin, Samuelson, to the usual New Classical suspects, up to Goodfriend, King, Blanchard and Woodford envisioned the links between macro and micro.

While these contributions do not answer Wren-Lewis and Smith’s questions, they clearly belie the kind of crude narrative provided by Williamson: “when the Phelps volume came out in 1970, micro and macro looked like they came from people living on different planets, and you had to convince people that it made sense to take ideas from Mars and use them on Venus.” A consequence of the intellectual hotpot of the 50s and 60s, a wider variety of approaches to microfoundations than is usually assessed were competing in the 70s, in the Phelps volume as in the macro literature at large. Economists were trying to derive consumption, investment and labor equations from formalized data-backed individual behaviors, working on adequate representations of search behavior, dealing with the consequences of the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu results. They were modeling heterogenous agents and coordination issues but wanted tractable models to estimate for policy evaluation purpose.

Historians could yet go even further in painting the diversity of the postwar intellectual landscape. The influence of economists’ tendency to pitch the history of macro as a war between two unified groups (Neokeynesians vs Monetarists, then New Classical vs New Keynesians) has created an biased focus on key characters such as Lucas, Sargent, etc. to the detriment of a wide range of research, such as disequilibrium modeling or sunspot theorists’ attempt to counter policy-ineffectiveness propositions while maintaining a general equilibrium framework with rational expectations. That such a variety of approaches coexisted in the 70s makes the New Classical takeover of the 80s even more dramatic.

Other pieces of HET scholarship show how key protagonists’ agenda are difficult to establish. They suggest that their agenda were presumably muddled and sinuous even to themselves for years, regardless of the apparent straightforwardness or simplemindedness emanating from Nobel reminiscences, or, say, Krugman’s account of the birth of RBC :

But many economists had so committed themselves to the idea that Keynes was dead and rationality roolz that they simply dug in deeper. Rationality-based microfoundations must be right; if their microfoundations couldn’t explain why nominal shocks have real effects, then nominal shocks must not have real effects – it’s all real shocks. And so real business cycle theory was born.

Warren Young’s combined analysis of protagonists’ recollections, unpublished drafts and referee reports sketches an altogether more tortuous path to Time to Build. Throughout the 70s, Kydland and Prescott chased a lot of rabbits in dozens of overlapping and changing drafts: replacing optimal control with a new way of evaluating policy rules, writing up dynamic equilibrium business cycle models, describing the cyclical properties of time series, finding impulse and propagation mechanisms, devising dynamic optimal taxation schemes. Accordingly they kept combining monetary and technology shocks, switching back and forth between dynamic game theoretic, general equilibrium and growth models, models with several heterogenous or single representative agents, with one or several sectors, with or without wage-stickiness or government expenditures.

How to win a science war?

Historians, then, do provide highlighting stories of macroeconomists’ intellectual development. Yet, the crucial issue is not how these ideas came into existence, but how they spread and became dominant. More specifically, the ultimate puzzle is how a bunch of less than 10 guys – Hoover notes that Lucas, Barro, Sargent, Wallace, Sims, Kydland and Prescott together account for 44 of the 81 articles of his anthology of New Classical macro – who neither agreed on the theoretical explanation of business cycles nor on the methods to confront those theories with facts (structural estimation? calibration? vars?) managed, in less than 10 years, to appear as carrying a common program, hijack a whole discipline and set the theoretical, empirical and institutional agenda. While’s everyone has his own opinion, there is no documented story of the offensive and its couterstrikes to be found. I believe writing such history would require:

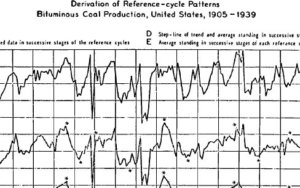

- a decompartmentalization of our field. In particular, writing the history of macro and econometrics together. Stories which beautifully wave economists’ econometric practices, their theoretical understanding of individual behaviors and aggregate fluctuations, their approach to policy, and the wider transformations of the US policy and political context in the 30s to 60s already exist. They show that macroeconomists have always been empirically minded. But I wonder to what extent the ties between macro and econometrics were of different nature after 1970. Economists were not merely using new techniques to test new models, they were coproducing them, and fighting the influence war on both fronts simlatenously. And since the key to the development of macro in the 70s and 80s seems to be the Lucas critique, a better understanding not only of how it was thought but also of of how it was understood, spread and accepted is required. I haven’t yet read Duo Qin’s new book on the history of econometrics after 70, but it looks promising.

- a greater awareness to the intellectual and institutional ecology of specific places. Understanding the genesis of rational expectations is not possible without a clear sense of what kind of intellectual hothouse Carnegie was in the 50s to 70s ( see all the works listed here, and follow closely Judy Klein’s research on the Cold War and Carnegie economics-as-engineering style as a craddle for macrodynamics). Similarly, understanding macro in the 70s 80s may require looking more closely at Minnesota, where Sargent, Sims, Wallace and Prescott were interacting in the dissertation committees of 2013 Nobel Prize Lars Hansen, Larry Christiano and Martin Eichenbaum, among many others, teasing each other’s econometrics with fancy “don’t regress, progress” jingles (see note 36), and actively contributing to the monetary policy views developed by the Federal reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Studying what the graduates were taught there may be a good idea. For New Keynesians, such crucial place may be the NBER, after it was reorganized under the leadership of Martin Feldstein, in particular its program on economic fluctuations, headed by Bob Hall.

- to drop the usual focus on a limited set of key academic papers. Economists’ recollections are riven with references to textbooks, readers, programatic introductions, and the like: what if the impact of Sargent 1979, Sargent and Lucas 1981, Sargent 1987, Blanchard and Fischer 1989, Mankiw and Romer 1991, Woodford 2002 was in fine as decisive as Lucas 1972 or Kydland and Prescott 1982?

-to study the changes in the reward structure of the discipline, the referee process, the academic publishing industry (see what economists say about the need to provide microfoundations to publish in a top journal)

-to look beyond departments of economics. What about other research bodies (NBER, Brookings, IMF etc.), central banks, policy makers, and the media? Who organized seminars, controlled discussion forums, provided publication outlets (count how many New Classical papers were first published in outlets edited by the Minneapolis Fed), who was whispering to the ear of such and such central banker, who governed the Council of Economic Advisers ?

From wishful thinking to active writing: missing data and pigeonholing

Granted, such wishful thinking is of little use, since we don’t have access to the data necessary to write such stories. While published articles and books are the first stone on which to build our narratives, they are far from sufficient. Roy Weintraub’s comments to Tom Scheiding’s thoughtful post, as well as Ezra Klein’s complaint against academic journals explain why published papers is a frustrating material. It freezes an entire intellectual and institutional process into a much constrained form. It collapses the initial identification of a puzzle, the compromises between co-authors, the technical trials and errors, successive drafts, workshop discussions, suggestions, revisions, the impact of peer-reviewing, the expectations of the publisher. Disentangling these various elements requires access to preliminary drafts, correspondence, workshop minutes, grant applications, referee reports. Tracking the spread of economic ideas similarly commands not only bibliographic work but also careful investigation of departmental and institutional records. Which usually comes with a 30 to 50 years lag. But the first thing is to make sure it will come, by worrying where the papers of Kydland, Prescott, Wallace, Romer, Fischer will be deposited, and how the archives of the NBER and US and worldwide central banks are curated.

There’s one final move to contemplate. Economic historians/philosophers/methodologists are driven by a variety of aspirations, such as assessing the theories and practices of contemporary economists, using fine-grained studies of “past” texts as another means (besides modeling) to contribute to contemporary public debate, or highlighting the sequence of events and the underlying individual and collective dynamics which had led economics to its current state of affairs, regardless of its desirability. While it doesn’t reflect any sort of pecking order, this post deal only with the latter kind of history, and a historian writing with different aspirations will rightfully advocate altogether different investigation methods. Which is not a problem. The problem is with the eternally simmering debate between advocates of more intellectual/internal/analytical and more institutional/contextual/external history. It is one not only utterly meaningless, but also potentially harmful for the quality of our work. Obviously, “contextual” historians have read and reflected on Lucas 1972 as well as on Christiano, Eichenbaum and Trabandt 2013. Obviously, “analytical” historians know that the theories developed by economists were influenced by the ideas and practices of their spouses, of central bankers, prime ministers, military bodies, foundations. And answering any of the questions listed above obviously requires the combination of both perspectives, if they can be separated at all. Less pigeonholing and more collaborative work is thus in order.