A look at America’s strange and dangerous approach to medicine, and how to fix it

Editor’s note: Journalist and author Maggie Mahar has written extensively about America’s distorted approach to healthcare. Her book, Money-Driven Medicine: The Real Reason Health Care Costs So Much (Harper Collins, 2006), was made into a 2009 film by Alex Gibney. In a 2-part series, Mahar shares her thoughts on wasteful medical spending, the Affordable Care Act, what’s possible under Trump, and more.

Americans can be glad that the Affordable Care Act has brought medical care to millions of the previously uninsured and underinsured. Nevertheless, our healthcare system remains hugely expensive and wildly inefficient.

Too often, care isn’t well coordinated. Meanwhile, we don’t have enough unbiased research showing which treatments are most effective. Everyone just assumes that the newest, most expensive product or procedure must be the best. As a result, we now spend over $3.3 trillion a year, or roughly $10,000 per person on healthcare —more than any other nation on the planet.

Why is our bill so high? It begins with overtreatment.

In Medicine, More is Not Better

In the laissez-faire chaos that we call a healthcare “system,” one out of three dollars is squandered on unnecessary tests, over-priced drugs, and treatments that provide little or no benefit to patients.

This may seem an outrageous statement, but nearly three decades of research done by doctors at Dartmouth’s Medical School demonstrate the waste. (Others, including McKinsey, the New England Institute of Medicine, and Dr. Donald Berwick, former acting director of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, confirm their estimate: 30 percent of the money we lay out for medical products and services does nothing to improve patients’ outcomes.) Part of the problem is that some providers simply order more tests and recommend more surgeries than others, yet research shows that their patients fare no better.

It doesn’t seem to matter whether a government-controlled program like Medicare or private insurers are paying the bills; in recent decades medical spending has headed toward the skies. From 1970 to 2006 private insurers’ reimbursements for care soared by an average of 9.7 percent each and every year. Medicare pays doctors and hospitals less, but even so, Medicare payments for medical services and products climbed by an average of 8.7 percent annually.

The point is this: Neither the public sector nor the private sector has found a way to cut the waste and rein in the underlying cost of care. Since the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010, health care inflation has slowed. But not enough: it still outpaces economic growth.

Follow the Money

If we want to trim the tab, it makes sense to ask: Just where is all of that money going?

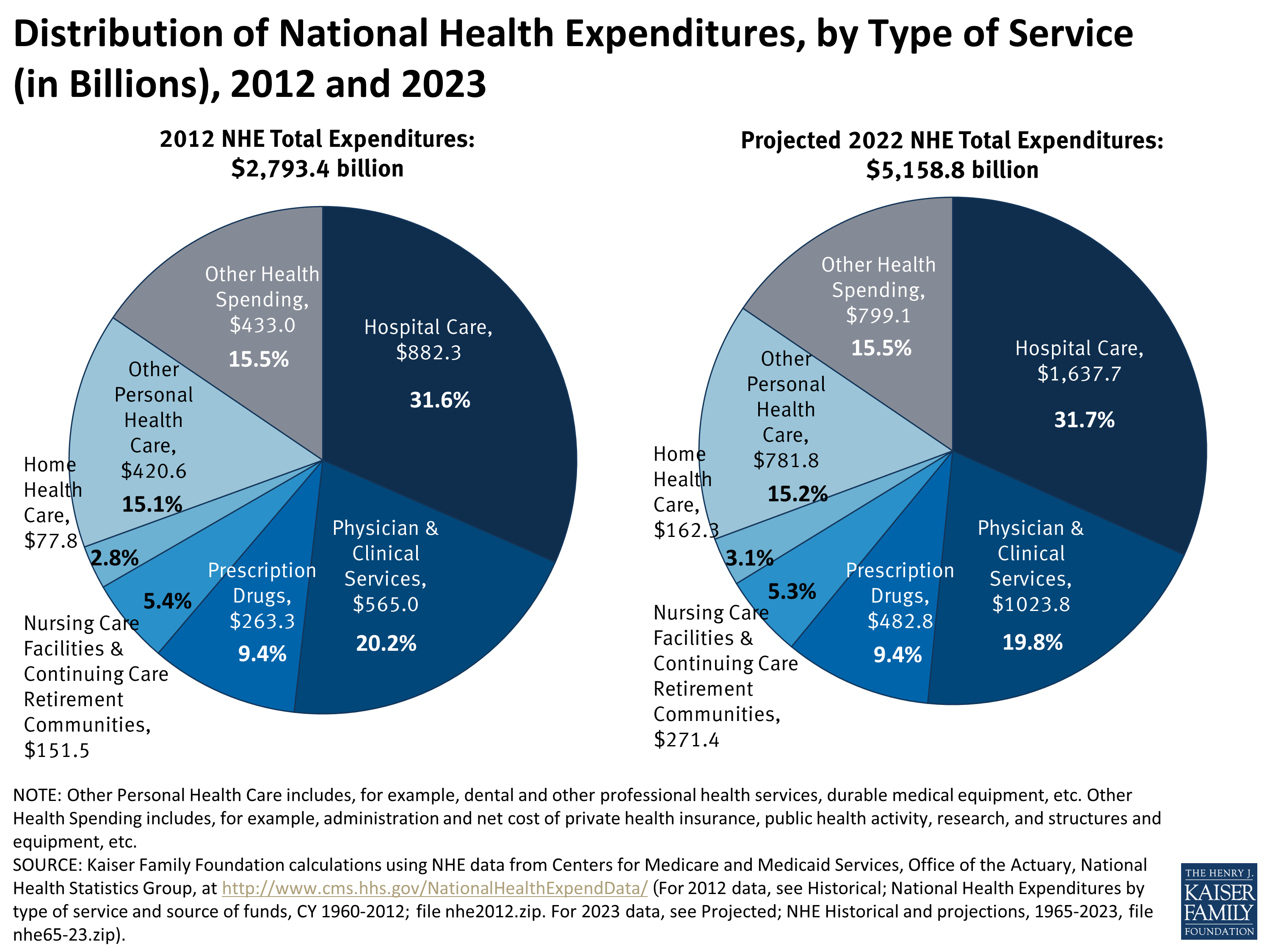

As the pie chart below shows, in 2012 roughly 60 percent of our health care dollars flowed to a combination of hospitals (31.6 percent), physicians (20.2 percent) and drug makers (9.4 percent).

Since the Kaiser Family foundation published this chart, doctors’ and hospital fees have climbed, while drug prices have skyrocketed (they now account for roughly 17 percent of the pie). Add in the rising cost of medical devices, which often are sold by pharmaceutical companies, and it’s safe to say those companies are drawing 20 percent of our health care dollars.

But what about the cost of private insurance? Many Americans believe that U.S. healthcare is so costly because we rely on for-profit insurers, rather the government, to deliver much of our care. Insurers’ critics suspect that a large share of our premium dollars go to fund lavish executives’ salaries, advertising, lobbyists — and profits.

But if you take a close like at the footnotes at the bottom of the pie chart, you’ll find that the “net cost of private insurance” is just one part of a rather small slice of the pie labeled “other health spending” (15.1 percent), a category that also includes medical research and spending on public health.

In fact, as a Commonwealth Fund report shows, from 2012 to 2014 insurers spent 87 to 88 percent of premiums just paying claims, leaving relatively little to pay the salaries of the thousands of employees who provide customer service, the clerks who enroll and dis-enroll customers, and all of the other administrative costs of a labor-intensive business.

The truth is that health insurance is not a hugely profitable industry; profit margins often run in the low single digits. By contrast large drug companies regularly report double-digit margins.

In 2014, the first full year of Obamacare, only about 1/3 of insurers generated any profit; the rest lost money. This explains why for-pofit insurers like United Healthcare are no longer participating in Obama-Care.

The folks who tell you that the ACA was drafted to enrich insurers just weren’t paying attention. Insurers went along with the plan only because they assumed Obama would be a one-term president — and then they could “fix it” to suit their own interests. I wrote about this here.

Under Obamacare, as more Americans signed up for insurance, we’ve seen that hospitals, doctors, drug-makers and device-makers gained more customers. For them, more patients mean more revenues. But for insurers, more customers mean more claims. Nevertheless, many Americans have convinced themselves that the Affordable Care Act represented a windfall for the insurance industry.

In a 2014 Washington Post column, Ezra Klein explains why this assumption is wrong:

“Insurers are the bogeymen of American health care. That’s in part because they’re the ones who say you can’t get something you want, who your bosses blame when they deduct more money from your paycheck to cover health costs…Politicians who routinely rail against for-profit insurers are scared to criticize those who do make money on Obamacare: for-profit hospitals, doctors or device manufacturers (though drug companies come in for a drubbing now and then). These are the people who work every day to save our lives, even if they make us pay dearly for the privilege. No one wants to blame them.”

Ultimately, if one of the goals of reform is to reduce the cost of care, the insurance industry is not the best place to look. That’s simply not where the money is. Klein sums up the facts:

“In 2009, Forbes ranked health insurance as the 35th most profitable industry, with an anemic 2.2 percent return on revenue. The pharmaceutical industry was in third place, with a 19.9 percent return, and the medical products and equipment industry was right behind it, with a 16.3 percent return. Meanwhile, doctors are more likely than members of any other profession to have incomes in the top 1 percent.”

The “Business” of Medicine

When all is said and done, what makes American healthcare unique — and uniquely expensive — is that the U.S. is the only country in the developed world that has chosen to turn medicine into a for-profit enterprise.

In Western Europe, a hybrid healthcare system includes both private insurance and government plans. The government regulates it, deciding how much doctors, drug-makers, hospitals and insurers can charge, but it doesn’t run the system.

By contrast, Canada & the UK have “single payer systems” controlled by the government. Everyone must have insurance and everyone must pay taxes to fund it.

But from the beginning, our health care system was built on a free-market platform. Traditionally we have treated medicine as more of a cottage industry, with individual doctors, drug-makers and hospitals making their own rules.

In the 1940s and1950s, doctors pretty much charged what they wanted, though their fees were quite small and often they charged poor patients nothing. After all, back then doctors didn’t have “miracle drugs” or MRIs. At best, they could comfort people, bear witness to their suffering, deliver babies and set broken bones. But as technology began to advance, and more and more people had access to that technology, medicine would become a growth industry.

This was one of the unintended consequences of Medicare. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson was determined to push Medicare legislation through Congress despite violent opposition from members of the American Medical Association, who wanted to keep the government from meddling in their business. Physicians feared socialized medicine and price regulation.

In an interview with Roger Mudd, one of LBJ’s advisors recalled a meeting where the president said: “We’ve got to get this bill out of the Way and Means committee, what will it take?”

Larry O’Brien, the administration’s liaison to Congress told him:

“We have to give doctors what they want and hospitals what they want.” (What they wanted, was the freedom to set their own prices).

“What will it cost?” Johnson asked

‘Half a billion dollars a year,” O’Brien replied.

Johnson said: “Only $500 million a year? Give it to them. Let’s get the bill.”

At about the same time, medical school enrollments doubled, thanks to a generously funded federal program, and Johnson reasoned that with more doctors in the marketplace, the cost of healthcare would come down. Johnson was wrong.

As usual, Medicine would ignore the laws of supply and demand. Sick people don’t comparison shop; someone dying of cancer doesn’t wait for the price of chemotherapy to fall.

Instinctively, Americans believed that more expensive care must be better care: You get what you pay for. When it came to their health, they wanted the best.

This is when healthcare inflation began to take off. With the advent of Medicare and Medicaid, the government put enough money on the table to seed a burgeoning industry. With both Washington and private insurers greasing the wheels of commerce, medicine was on its way to becoming a highly profitable business.

Up until that point only 70 percent of the population had health insurance, and often it only covered hospital costs, not doctors and drugs. Now seniors and many of the poor had access to care that reimbursed for physician visits as well as hospitals stays. Only Medicaid put a limit on prices — this is why many doctor refused to take it.

Following Medicare’s example, more employers began to offer comprehensive health insurance. After all, they could write off the cost on their taxes. At the same time more physicians became specialists, and as their numbers increased, so did their fees.

Meanwhile a burgeoning industry attracted entrepreneurs who would invent an endless stream of new services and products. Everyone knew there was money to be made. Inevitably, in the1960s, the for-profit hospital was born.

From 1960 to 1970 the nation’s health care bill snowballed from $27 billion to $73 billion. Along the way, the government’s share soared: in 1965, taxpayers shelled out 10.8 billion for healthcare; five years later, they paid $27.8 billion.

The New, New Thing

In the 21st century, what is the biggest factor pushing our healthcare tab higher?

“Innovation,” says Princeton health care economist Uwe Reinhardt. Speaking at the World Healthcare Congress Europe in 2008, he explained that our for-profit healthcare industry “will continue developing new stuff.” Will that “new stuff” — in the form of new drugs, devices, tests, and procedures — be worth it?

Some of it will be, and some of it will not.

As medical technology advances —and becomes more expensive —it does not necessarily become more effective. A 2006 study in the medical journal Health Affairs reveals that over the preceding decade, while spending on new technologies designed to treat heart disease climbed, the share of patients who survived flattened out.

In many areas, we seem to have reached a point of diminishing returns.

It’s time for evidence-based medicine — healthcare based on objective research comparing the effectiveness of various treatments for individual patients. That is what the Affordable Care Act sets out to do.

*In Part 2 of this post I will discuss the ACA, whether it will be replaced, and how it can be improved.