To be clear, what I am going to say is not very deep. The events are too recent and painful. They left me speechless for a couple of days and there’s nothing really bright that can be said on such a dramatic occasion. Seventeen people have been killed and my thoughts, as those of the millions of people who chose either to protest yesterday in the streets or to reflect upon the sad situation at home, go first and foremost to the victims.

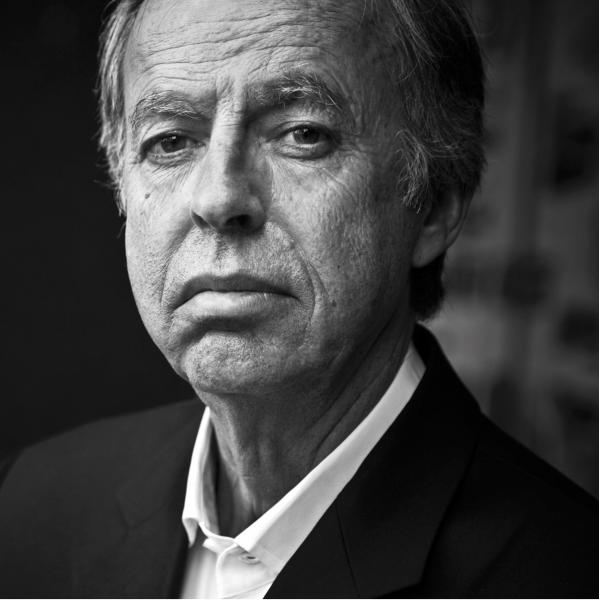

Among them, there was a fellow economist, Bernard Maris (1946-2015). While the focus has been on the cartoonists who were shot during the Charlie Hebdo killing, it is important to remember that other people were killed during the assault: a copy editor, a psychoanalyst, a cleaning operator, a cultural activist, two policemen and, then, an economist. Maris was well known in France as an essayist and as one of the main economic experts on the French public radio France Inter. Because his branch of economics was non-mathematical and he did not use formal models, he was often overlooked by fellow economists for not publishing in professional journals, offering instead his views, expressed verbally, as a public intellectual. Yet, unbeknowst to the public, and maybe to some professional economists, Bernard Maris was a University Professor, who had begun his career at the University of Toulouse from 1975 to 1994, when he passed the ‘Agrégation de l’Enseignement Supérieur” (the competitive exam that allows you to become a full Professor in France) and moved to the Institut d’Etudes Politiques there. So he was in Toulouse with the more mainstream - and equally missed - Jean-Jacques Laffont, as well as with the recent Nobel memorial Prize recipient Jean Tirole, who joined in the early 1990s. What an unlikely cohabitation it must have been! Maris was a heterodox economist who was very critical of mainstream economics, and expressed his views in widely diffused economic essays - which, ironically, some French students have used as introductory textbooks. He had begun his career working on distribution theory - in a neoclassical growth model - but had since then diverged a lot from mainstream economic theory, becoming an exegete of Keynes, and lately, focusing on the relaton between economics and literature. He had also been appointed to the board of the Banque de France in 2012. When I listened to Maris’ economic analyses on the radio, I quite often - but not always - disagreed with his views. Yet it must be recognized that he was a good vulgarizer of economic thinking. That is not, anyway, the point I want to make. My point is that, like his fellow Charlie Hebdo writers, he was killed because he worked for a publication whose caricatures had been considered insufferable by a number of religious extremists. Maris was not only a contributor to Charlie Hebdo, he was one of its co-owners and a defender, not of freedom of speech as many believe, but of the right to be offending, irresponsible and inconsequential.

This brings me to my second point. A lot of people in France, as well as in the rest of the world, want to interprete the killings as a blow against freedom of speech. That has been the main focus of the protests and the debates that followed. One question in these debates, especially in the British and American press, has been to assess whether freedom of speech is a universal concept that should be defended no matter the consequences and, therefore, whether newspapers and magazines located in free countries should publish the cartoons, even if they find them insulting - even racist. This is a very complicated debate, one that shows that free speech is an ultimately relative concept. As a French person, who has lived in the United States, I understand very well why an American editor would/should be reluctant to publish Charlie’s cartoons: they were just not meant for an American audience. That type of mean, filthy, sometimes silly humor has a specific story in France, one that involved the Gaullist period and its frequent anti-liberty practices when it came to the press. Charlie Hebdo was created in 1970 after another newspaper, Hara Kiri, had been shut down by the government for publlishing a very offensive joke about Charles De Gaulle’s death. Hence the name Charlie, a very informal way to call the late President. An emanation of governmental censorship, Charlie Hebdo would continue to exist to test the limits of free expression, but in a very French way: with a lot of bad taste. The cartoonists were all coming from the anarchic tradition, they despised organized religion in all its forms as well as a lot of other -isms, including frequent attacks against feminism and communism. To say that the cartoonists at Charlie were racist - or islamophobic - is a bit of a misjudgment, because the truth is that those guys did not like a lot of things or people in the first place. When I was a freshman at Nanterre, I used to buy Charlie and my favorite section in the newspaper was the weekly column written/drawn by the then younger Stéphane Charbonnier - aka “Charb” - entitled: “Charb doesn’t like people”. Though I see similarities between Charlie Hebdo’s cartoonists and some American graphic novelists - I think about people like Chester Brown or Joe Matt, for instance -, I must say that there’s nothing quite like Charlie Hebdo in the United States. American cartoonists, when they produce some provoking stuff, do it in a more confessional vein or, on the contrary, situate themselves in a larger tradition of critical inquiry - think about Joe Sacco, for instance. Unlike these traditions, Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons were, most of the time, apolitical and amoral. They had respect for nothing or no one, not even for the dead. For this reason, the geopolitical consequences of their publishing the Muhammad cartoons were far beyond their grasp. What they perceived as silly entertainment was interpreted as grand political - religious, social, even racial - statements. The resulting story is, like most of the narratives we write in our history of economics/science paper, one of incommensurability: creative communities who end up facing some very strange culture they do not understand and that do not understand them. But our papers rarely end with a blood bath and a worldwide reaction. That makes the death of these cartoonists - and policemen, psychologist, cleaning operator, receptionist or economist - all the more absurd and saddening.

UPDATE: Thanks to one of my friends, I came across a blog post that does some good job at clearing out misunderstandings concerning the Charlie Hebdo cartoons. As it is intended, I think, for an audience of educated left-wing people,it will not completely erase the incommensurability issues I am evoking but it is interesting, nonetheless.