The $1.9 trillion stimulus should be large because the need is large

The $1.9 trillion relief package is on track to pass in March but not without a struggle and with some important details still uncertain. The price tag is big, coming on the heels of the nearly $4 trillion Congress appropriated last year. That’s six times the fiscal relief in the first two years of the Great Recession. Even without the new package, the U.S. federal debt is more than GDP, according to the Congressional Budget Office, a level not seen since World War II.

With the stakes so high, disagreement among economists, even those who normally agree with each other, is heated. The question is whether spending at this level is necessary for full recovery or will instead overheat the economy. It appears that the inflation hawks have lost this skirmish, but the war is only getting started.

In the ranks of the inflation hawks are many revered macroeconomists. Most vocal are Larry Summers, a former Secretary of the Treasury, and Olivier Blanchard, a former Chief Economist at the International Monetary Fund. John Taylor, Greg Mankiw, and Bill Dudley have raised similar concerns. On the other side are Janet Yellen, current Secretary of the Treasury, Jay Powell, current Chair of the Federal Reserve, Paul Krugman, a past Nobel Prize winner, and Gita Gopinath, the current Chief Economist at the International Monetary Fund, among others.

All the sound and fury have recently unsettled bond markets. Last week, 10-year Treasury rates briefly hit 1.5% and remain at their highest levels since the pandemic began. Market-based inflation expectations moved up sharply, though their break-evens reflect other factors besides expected inflation. Nevertheless, inflation hawks point to these market signs as evidence of the risk that more deficit spending would push up rates and increase the government’s costs of servicing the federal debt. The markets steadied soon thereafter but the path forward in financial markets is far from certain. Moreover, as is always the case with markets, it is impossible to pinpoint the cause of day-to-day movements.

A critical review of the claims in this debate is plainly necessary. This essay focuses on four main areas of debate: potential output, inflation expectations, targeting on need, and pent-up demand. In each case, the data, research, and prior experience strongly suggest that the risks of doing too little far outweigh the risks of doing too much. The hawks raise valid points, but given what we know now, overheating is unlikely.

The $1.9 trillion package is not too big, it’s our estimates of capacity that are too low.

The risk of overheating rests on the dubious assumption that the relief package will create more demand than can be met easily and will thus lead to uncontrollable inflation. Recent data do not support that gloomy scenario. With ten million fewer jobs than prior to the pandemic, the case is strong to do more to support demand and a rapid recovery in the labor market.

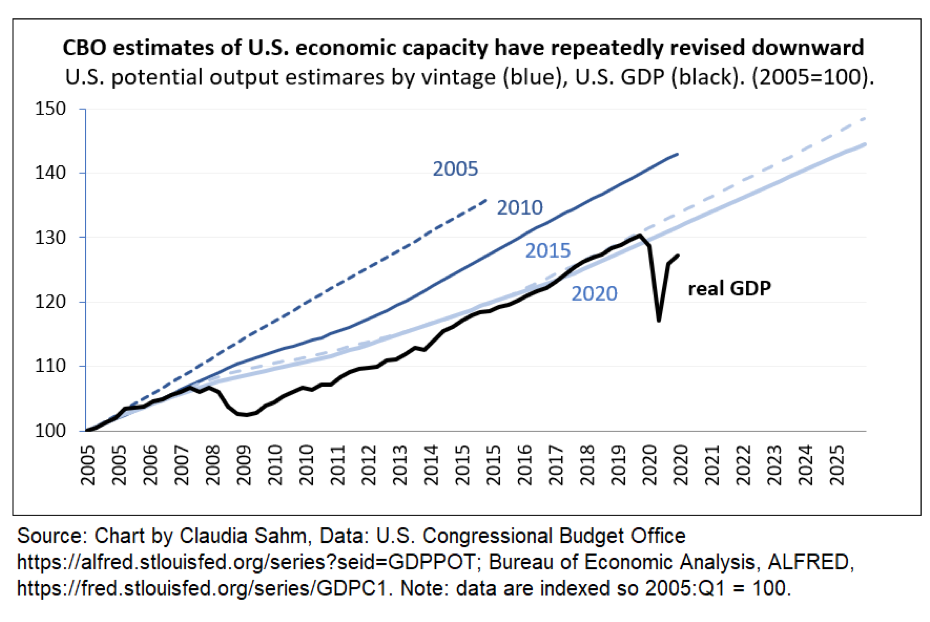

Making the same mistake that so many did in the policy debates of the Great Recession and its painfully slow recovery, the hawks are underestimating the economy’s capacity. They base their argument on elementary comparisons of potential output from the Congressional Budget Office and GDP from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. That approach is outdated and flawed.

So, what is potential output and why is it so prominent in this debate? It’s the level of GDP beyond which inflation would pick up: the point at which demand outstrips supply and prices in general begin to rise. Once inflation picks up the fear is then that it would quickly become uncontrollable.

Conceptually, the hawks’ focus on the difference between GDP and potential output—the so-called output gap—is sensible. But they breeze past the commanding fact that similar calculations during the Great Recession understated the shortfall in demand and led to policy responses that were far too small.

Let’s look at Blanchard’s arithmetic on potential output:

“In January 2020, the unemployment rate was 3.5 percent, the lowest since 1953; it can reasonably be taken as being close to the natural rate. Put another way, output was probably very close to potential. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated the potential real growth for the past few years at around 1.7 percent. Given that actual real GDP in 2020 Q4 was 2.5 percent below its level a year earlier, this CBO estimate implies an output gap in 2020 Q4 of 1.7% + 2.5% = 4.2%, or, in nominal terms, about $900 billion.”

His math checks out, but his assurance does not. For years after the Great Recession, estimates of potential output have been revised downward again and again. See Figure 1. For example, in its forecast published in 2010, CBO expected potential output in 2020 to be $4 trillion (in nominal dollars) higher than its estimate it published in 2020. Using CBO’s earlier forecast and the BEA’s current estimate of GDP, the output gap would be $2½ trillion. That’s more than the relief package and nearly three times Blanchard’s estimate.

The radically different views about the shortfall in output is no simple coding error. They do not reflect a rethinking of CBO’s methods over time. The dramatic differences are the direct result of years of economic distress after the Great Recession and a policy response that was profoundly lacking. It is widely understood now that the output gap was much larger in 2009 than we thought. Summers, who was then the Director of the National Economic Council, could not have known how dramatically the estimates of potential output would revise down. He could not have known how tragically small the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act would prove to be. But he and the other inflation hawks should know better now. How many times do they have to put the economic well-being of American families at risk? Yes, the time could be different. The relief package could be more than the bare minimum. But that thinking was disastrous in the past recession and is a risk too large to take again.

Figure 1

It is unlikely that the U.S. economy could quickly reach the levels expected in 2010. But this exercise illustrates how a timid policy response in the face of the Great Recession led to immense damage in our productive capacity. It is likely that the economy could return to its pre-Covid operation, and with ten million jobs fewer than before the crisis—a larger shortfall than any time in the Great Recession—substantial unused capacity remains.

There are other problems with focusing on current estimates of aggregate GDP. First, the headline number masks a dramatic shift in the components during the Covid crisis. Specifically, services spending, which was half of GDP in January 2021 remains $650 billion lower at an annual rate. Goods spending, in sharp contrast, is $500 higher, and the bulk of that increase comes from outlays on durables. It is striking that the rise occurred rapidly and did not result in uncontrollable goods prices inflation. The second problem is that GDP has become increasing unequal across households. In the new package, contrary to some widely publicized claims, cash relief is targeted to most families, not the wealthiest. Finally, it is important to remember that GDP is subject to revisions, which can be substantial. The BEA release states, “The GDP estimate released today is based on source data that are incomplete or subject to further revision by the source agency.” During the last recession, the downward revisions in GDP were large. Initially, the BEA estimated that GDP declined about only ¼ percent during the four quarters of 2008. The current estimate for 2008, after years of revisions, is a decline of 2¾ percent. It is unwise and at odds with past experiences to assume that the first read on GDP in 2020 fully captures the depths of the Covid crisis. Using current estimates of GDP to judge the output gap could lead us to do too little, as we did in the Great Recession.

We know from the Great Recession that revisions to actual and potential GDP can dramatically change estimates of the output gap. When the Obama Administration took office in 2009, the GDP gap was estimated to be -3%. Within a few years, as discussed in (Sahm, 2015), the estimate of the gap widened to -5%. It’s clear now that the that relief in 2009 should have been much larger. Fiscal restraint cost the American people dearly, and we must not repeat the mistake.

I am not the first to question the standard approach to output gaps. Fontanari, Palumbo, and Salvatori (2019) discuss the construction of CBO-style estimates—developed by Arthur Okun over 50 years ago (1962). They propose an alternate approach that does not depend on unobservables like the natural rate of unemployment and show that it produces better, more stable estimates of economic capacity. They argue that the massive drop in demand in the Great Recession did not lower long-run growth prospects as the CBO revisions suggest. Rather, because of the ways output is usually assessed in mainstream theory, the fall in incomes created enormous gaps relative to true potential output. They argue that the policy should have been much more aggressive in the Great Recession. Likewise, substantial relief is needed now.

Coibion, Gorodnichenko, and Ulate (2018) provide three other estimates of potential output in 2016—a time when the Federal Reserve justified the first increase in interest rates since the Great Recession on the belief that we were nearing full employment and risking overheating. Fed officials now view that step as premature. Other estimates, including Blanchard and Quah (1989), Galí (1999), and Cochrane (1994), all show markedly larger gaps and less cyclicality than those based on CBO’s approach.

Coibion et al. examine a full range of dynamic properties in potential output estimates and conclude that CBO’s framework understated how much the economy could grow in 2016 without overheating. Their analysis predates the Covid crisis by three years, but their work highlights potential problems in recent CBO estimates. To be clear, their findings do not prove that CBO’s current output gaps are too small now or then. But their research underscores the uncertainty around such estimates. Taken together, these problems suggest that it is a mistake for inflation hawks to rely so heavily on them.

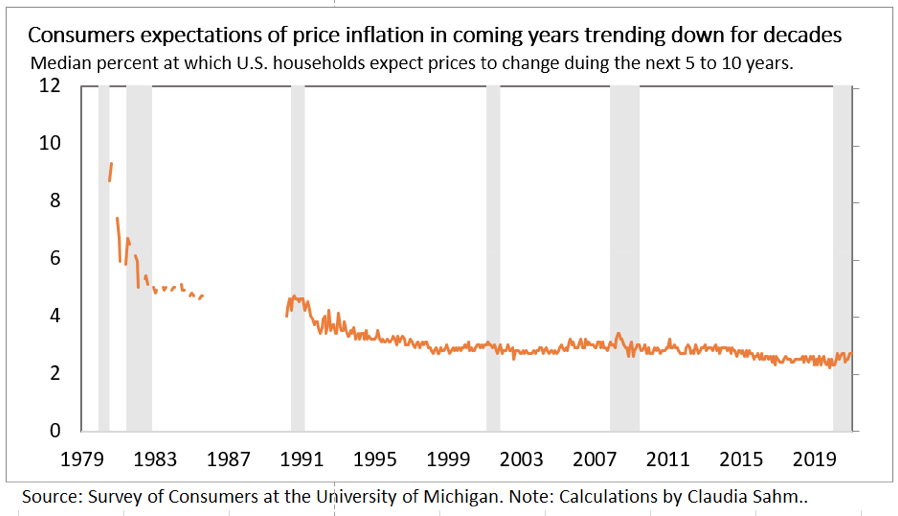

Inflation expectations among families are unlikely to move up and put pressure on inflation higher.

During the past few decades, actual inflation and expected inflation among families have been low and stable. Many economists credit monetary policy for stable, low inflation and creating the expectations of a similar path going forward. See Figure 2. The stability is referred to as “anchored expectations.”

Figure 2

Inflation hawks worry that the celebrated trade-off between unemployment and inflation, which weakened substantially over the years, as noted in Blanchard, Cerutti, and Summers (2015), could return with trillions of dollars in fiscal spending. They warn of “regime change” in which uncontrollable inflation comes roaring back. They argue that expecting higher inflation will untether expectations, leading to a self-fulling prophecy of more inflation: Workers would demand higher wages, employers would have to raise prices, causing more inflation. If the Federal Reserve were to wait, as Chair Powell (2020), has promised, to raise interest rates only after a period of sustained inflation, expectations might come unmoored. That would force the Fed to raise rates rapidly and risk a downturn.

But the data on expectations do not support such strong causal links. As Jason Sockin and I show, consumers for decades have paid little attention to news about inflation. Likewise, Detmeister, Jorento, Massaro, and Peneva (2015) demonstrated that inflation expectations among consumers do not respond to Fed announcements of more accommodative policy. Contrary to warnings of the hawks, the risk of “unanchored” inflation, after years of stable expectations, is low. In contrast, market-based measures of expected inflation have been volatile lately, but their expectations are more sensitive to policy announcements than consumers. Moreover, markets have considerable policy news to digest with the Fed’s new monetary policy framework and with massive fiscal relief from Congress. Consumers tend to tie their expectations to the inflation they personally experience, so bumps and wiggles in financial markets are unlikely to move consumer expectations and set off a price spiral.

Inflation experts at the Federal Reserve Board, such as Rudd (2020), show convincingly that underlying inflation remains low and persistent. Nor is it likely to step up quickly. As Federal Reserve officials have said repeatedly, they expect pent-up demand to push inflation higher temporarily after the economy reopens. In such a scenario, the Federal Reserve would not raise interest rates to cool the economy. In fact, after a decade of low inflation, Fed Chair Jay Powell sees some more inflation as welcome, allowing the Fed to meet its 2% inflation objective. He views doing “too little” fiscal relief as a larger risk than “too much.” The Federal Reserve—an institution known for its long history of inflation fears—sees little prospect of overheating. Put bluntly, the inflation hawks are out of touch with reality, again.

Inflation phobias are hard to quell, especially among economists who lived through the era of high inflation and high unemployment—referred to as “stagflation.” Malmendier, Nagel and Yan (2021) show that personal experience with high inflation helps explain the behavior of inflation hawks on the Federal Open Market Committee since the 1950s. Many inflation hawks outside the Fed share that same background.

Ironically, recent research suggests that we may have taken the wrong lessons from stagflation. Using geographically detailed data, Hazell, Herreño, Nakamura, and Steinsson (2020) find that changes in unemployment since the early 1980s had essentially no effect on inflation dynamics. Moreover, the world has changed over time and disinflationary pressures appear to have increased. Stock and Watson (2020) argues that globalization is one factor holding down inflation. It is possible that inflation could pick up as the federal debt climbs higher this year. But it is more likely that personal experiences decades ago and a misplaced faith in the unemployment-inflation tradeoff are leading the inflation hawks astray.

The selective memory of the inflation hawks is frustrating. They remember stagflation clearly like it was yesterday, but they forget the Federal Reserve’s decades of experience since then at keeping inflation under control. As Powell has said repeatedly, they are ready to act if the economy starts to overheat. No one wants to see uncontrollable inflation take root. The Fed knows how to fight inflation. The inflation hawks need a whole series of bad events for their doomsday scenario to come true. Each of these events is less likely than the next. In contrast, it is easy to see the scarring scenario come to pass. Doing less, as the hawks argue, would push that likelihood dangerously high.

$1.9 trillion should be large because the need is large.

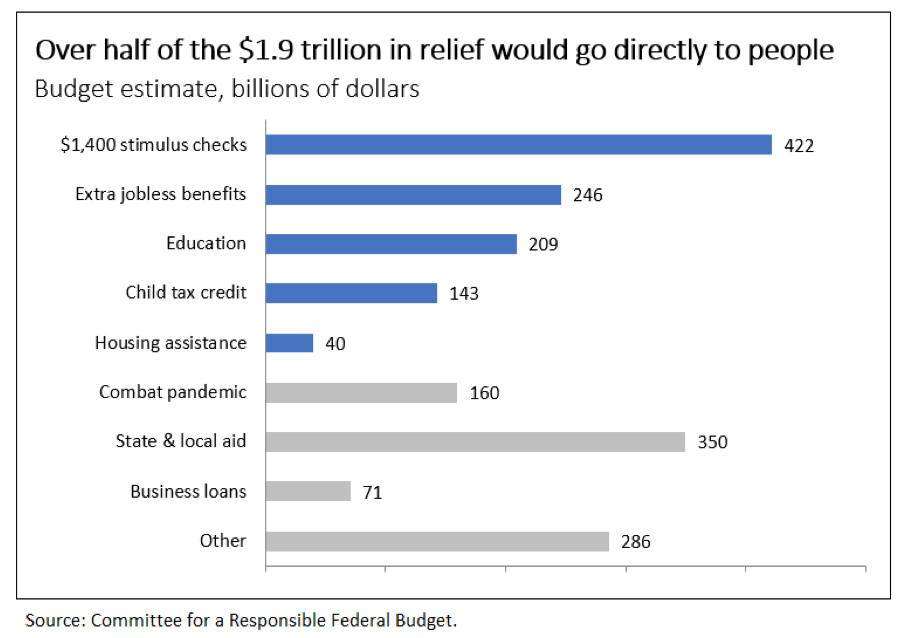

A weak, if now very common, critique of the relief package is that it is “beyond the imperative of relief,” in Summers’ words. Inflationist hawks point to how aggregate employee compensation is back on track.

But narrowly focusing on aggregates is the wrong way to judge the current situation among families. The need remains widespread and urgent. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, half of U.S. families lost employment income last year and less than one fifth received jobless benefits. Millions are behind on paying their rent, mortgage, and student loans. Food banks remain under stress. The breadth of suffering and the gaping holes in our safety necessitate broad relief. Yellen argues, “I want to make sure that Americans don’t suffer needlessly…I think we know what those needs are, and we need to act forcefully.” Over half of the money would go directly to families, including stimulus checks, unemployment benefits, education, housing assistance, and child benefits. See Figure 3. The indirect effects, from ending the pandemic to helping small businesses, will benefit families and workers too.

Figure 3

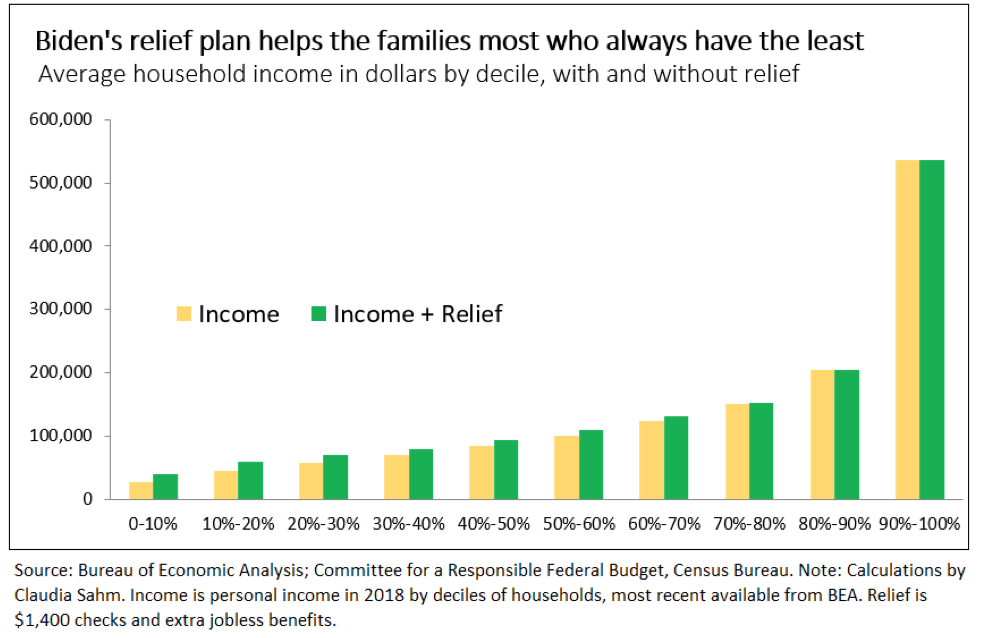

The current stage of the economic crisis differs from the situation last spring when the CARES Act passed. Our economy was in free fall then. Congress, the President, and the Federal Reserve moved quickly to pump trillions of dollars into the economy. It worked. Over the summer we clawed back half of the 20 million jobs lost in the spring. Yet, 10 million jobs are still missing–a loss larger than that in the depths of the Great Recession. And yet aggregate employee compensation has recovered. How can that be?

The answer has to do with the massive income inequality in the United States. Aggregate personal income—the largest component of which is employee compensation—is dizzyingly skewed toward the highest income families. In 2018, the most recent available data, the bottom 60% of households by income have less aggregate income than the top 10%. And the top 10% has markedly more income than the next 10%. Keep in mind that the famous $1,400 checks go the bottom 80% of households and the extra unemployment benefits are even more skewed to lower income families See Figure 4. It is important to remember that many Americans—not just those with low incomes—live paycheck to paycheck with little if any savings (Weidner, Kaplan, Violante, 2014). The need is always there, especially now.

Figure 4

A tepid policy response now risks locking in even more inequality. Inequality worsened during the Great Recession and its slow recovery. In 2018 the top 10% by personal income had $2.5 trillion more in personal income than in 2007. That is two and half times more than the aid to families in the new relief package. The $1.9 trillion package fights today’s crisis and the threat of even more damage.

A big relief package is necessary for a rapid recovery for all.

Without a big new relief package the labor market recovery could take until early 2023, a full three years after the Covid crisis began. With the relief package of the size the President is proposing, recovery should come much sooner. The inflation hawks are wrong. They are denying the obvious solution: more federal spending. After the CARES Act, spending and savings among families and the unemployed picked up rapidly, but as relief ran out, progress stalled. Consumer spending in January suggested that the $600 checks enacted in the December package once again spurred demand. But inflation hawks are not correct to argue that families are so flush with cash that additional checks will do nothing to stimulate spending. Experience in the Covid crisis and prior recessions shows undeniably that relief works. We are far from the finish line now and relief will get us there faster. Congress must do more. The risk of scarring looms larger than of overheating.

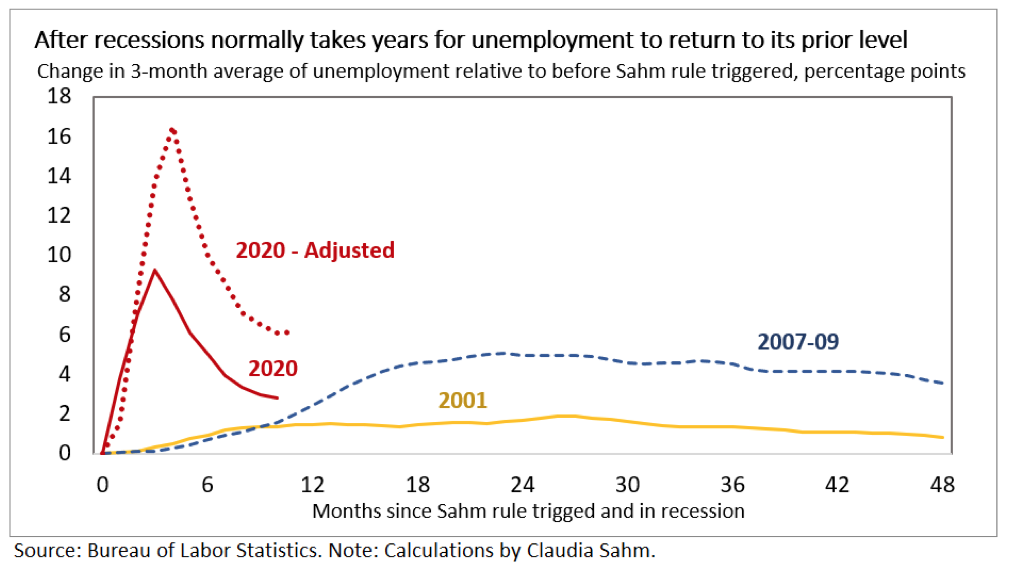

Yes, Americans entered the Covid crisis in a better place financially than before the Great Recession. Household debt levels are far more manageable in 2020 than in 2007. The financial system was better capitalized and more closely monitored than before the global financial crisis. The shock that pushed us into recession was different too: a global deadly pandemic, not a bursting housing price bubble. It is reasonable to expect the direct effects of Covid will dissipate faster than those of real estate prices in the Great Recession. However, a year into the current crisis the job losses reman massive. Moreover, we know from the 2001 recession, led by a tech bubble in the stock market and preceded by 4% unemployment, that even a mild recession can hold back the labor market for years. In fact, the unemployment rate had not returned to its pre-2001-recession level when the Great Recession began.

Since 2001, jobless recoveries where the labor market lags GDP have been the norm in the United States. Another would be devastating. The real unemployment rate—adjusted to include the millions who have dropped out of the labor force in the pandemic—is close to 10 percent, which is 6 percentage points above its pre-recession level. See Figure 5. The rapid improvements we saw early in the recovery slowed in the fall, even before the recent surge in Covid cases and deaths. To close the current shortfall in payrolls, we would need to add one million jobs, on average, every month for the rest of the year. More relief could help us achieve that ambitious goal. Wringing our hands over the low inflation risk will not.

Figure 5

We do not already have “all the ingredients for a booming economy,” and more relief will not “light a fire” leading to uncontrollable inflation. Let’s face facts: millions of Americans are suffering, the cleavage between the haves and the have nots is widening, and relief works. We need a robust recovery. The economy does not have the tailwinds to heal itself. Finally, for the inflation hawks to be right we would need to see wages as well as prices pick up substantially. With mass unemployment now that’s nearly impossible this year. Moreover, wages grew slowly well into the prior expansions. They are unlikely to take off even when most people are back to work.

Conclusion: Complacency, not inflation, is enemy number one. Congress must do more.

Now is the time for action. Now is not the time for inflation fears. The need is to do more is immense, and policymakers must deploy every tool they have. It is appropriate to consider the risks of overheating and the risks of suffering. It is not appropriate to downplay the suffering. The evidence and the research clearly show that the risks of doing too little are ones on which we should base policy. The hawks are peddling outdated thinking. When the world changes, we must change, especially when our decisions and advice could affect millions of people. It’s time to listen to Americans and help them back on their feet quickly. It’s time to build an economy that works for everyone.

The inflation hawks are wrong. Congress must go big.