Ransomware gangs have been causing extensive damage. It’s time that the government takes them more seriously.

Ransomware Operators Are Increasingly Acting Like Terrorists

One brazen incident has created a sense of urgency and catalyzed an acute awareness of the impacts of ransomware. The flow of roughly 45% of the fuel consumed on the East Coast of the United States has been halted because Colonial Pipeline’s information technology (IT) systems (computers, applications, and data) were hijacked by DarkSide, a ransomware operator with links to Russia. Colonial’s temporary halt of its pipeline operations was a proactive measure to protect those systems from being fatally encrypted like other parts of its corporate network.

The result has been fuel shortages and a surge in prices. The timeline for full (and safe) restoration is still unknown. This event has broadly impacted millions of Americans and received significant media coverage, but it is not unique or isolated. In fact, the U.S. Department of Justice claims that at least 4,000 ransomware attacks occur daily[1] and security firm Check Point observed that an organization fell victim to a ransomware attack on average every 10 seconds in 2020.[2]

Ransomware gangs have been hijacking the IT systems, data, and operations of our hospitals, schools, corporations, and critical infrastructure services — thereby disrupting civil order and stability by interfering with the peace, security, and normal functioning of our communities. The ransomware operators’ principal tactics include intimidation, coercion, and extortion until the victim entity capitulates to their demands in order to avoid future injury or secondary effects. Hijacking institutions, intimidating people, coercing companies to pay a ransom, causing serious physical property damage, and disrupting civil order are all threats to the economic prosperity and security of the United States and should be treated as acts of terror. But little has been done to prevent such attacks; and it is time for authorities to start taking action including classifying ransomware activities as a form of terrorism.

A Threat to Healthcare Providers and Citizens’ Safety

Harm and injury are on the rise as the frequency and cost of ransomware attacks continue to grow exponentially. At the top of the list are often hospitals and healthcare facilities. In September 2020, Universal Health Services (UHS) fell victim to a human-operated ransomware by the Ryuk gang. The event crippled all of the UHS systems in the U.S. and caused outages to computers, phone services, internet connectivity, and data centers. Some facilities were forced to turn away patients and ambulances, cancel surgeries, and resort to filling all patient information on paper.[3] In order to prevent catastrophic harm and further spread of the malicious activity, UHS took down the rest of its systems used for medical records, laboratories, and pharmacies across about 250 of its U.S. facilities.[4] The Ryuk gang’s ransom demands typically range between 15 and 50 Bitcoins, or roughly between $100,000 and $500,000.[5] In October 2020, the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued a joint alert for the healthcare industry warning them of the imminent threat presented by the Ryuk and Conti ransomware gangs who are seeking financial gain.[6] In the midst of a global pandemic and as more COVID-19 patients were entering hospitals, these gangs exploited vulnerable institutions and citizens — threatening patient care and citizen safety. Lives are already at risk and these terrorists are taking advantage of the fragility, distraction, and fear of society to co-opt and coerce for economic gain.

A Threat to Educational Institutions

Between January and April 2021, there were over 20 disruptive ransomware attacks in the U.S. education sector, affecting over 550 schools. In March, for example, Broward County Public Schools in Fort Lauderdale, Florida — the nation’s sixth-largest school district with an annual budget of about $4 billion — fell victim to the Conti ransomware gang. Conti was able to encrypt Broward’s servers and exfiltrate more than one terabyte of data files that included personal information of students and employees as well as other important financial and contractual data.[7] The gang then threatened to erase the files and release the students’ and employees’ personal information unless a $40 million ransom was paid (the demand was later dropped to $10 million). After two weeks of negotiations, the district offered to pay $500,000 to retrieve the data, and on 31 March it announced it actually had no intention to pay the ransom (presumably because they couldn’t agree with the ransomware operators).[8] On 19 April, the Conti gang made good on their threat and released 26,000 of the stolen files, including Broward School District accounting and other financial records, such as invoices, purchase orders, travel and reimbursement forms, and hundreds of utility bills.[9] In addition to the reportable breach, the incident caused a brief shutdown of the district’s computer system, and the school warned that the attack could affect the ability to pay employees. Soon after this incident, the FBI published a Flash Alert warning that the operators of PYSA (which stands for “Protect Your System Amigo”) — providers of ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS)[10] — were targeting higher education institutions, K-12 schools, and seminaries in at least 12 U.S. states and in the United Kingdom. The FBI explained that these malicious “actors use PYSA to exfiltrate data from victims prior to encrypting victim’s systems to use it as leverage in eliciting ransom payments.”[11] According to the Alert, the FBI has observed PYSA targeting government entities, educational institutions, private companies, and the healthcare sector since March of 2020.

In September 2020, the Fairfax County Public School system — just a few miles from the Nation’s Capital — fell victim to the Maze ransomware. While the school did lose protected information of both employees and students, the incident did not impact online education. At the time, the school’s Superintendent noted that it was just one of more than 1,000 educational systems to have suffered a ransomware attack in the past year.[12] Worth noting, however, is the fact that if an active shooter came into a school, as we have seen in Parkland, Texas and every other state in the U.S., we would activate emergency responders and treat it as a terror event. Ransomware attacks, instead, are still been treated as low-level crimes or an embarrassment to hide despite the significant disruption that they can cause. Our students and faculty are being stalked online, their information is being illegally copied and exposed, and worse, their community’s institutions are being hijacked for money and made no longer operational. Schools are no longer a safe place. This is more than a crime.

A Threat to Corporations and Critical Services’ Resilience

No sector is without compromise and 2021 proves to be an even more challenging year. Ransomware attacks increased by at least 485% in 2020 compared to 2019.[13] On 23 March 2021, CISA and the FBI issued a joint alert warning that another strain of ransomware, called the Mamba ransomware, “weaponizes DiskCryptor — an open source full disk encryption software — to restrict victim access by encrypting an entire drive, including the operating system…[and that] it has been deployed against local governments, public transportation agencies, legal services, technology services, industrial, commercial, manufacturing, and construction businesses.”[14]

The Mamba operators are just building on the progress made by other groups. For example, in 2020, Maze operators targeted many brand-recognizable companies, including Chubb, LG, Xerox, and Canon. They were one of the first ransom groups to initiate the double extortion scheme: steal unencrypted files before encrypting the victims’ data and business critical systems, and then threaten to publicly release the stolen data if a ransom is not paid. Companies often confront the difficult decision of having to pay the ransom to prevent public release of their corporate proprietary and/or protected data as well as to obtain the keys to decrypt their systems and data sets.

If the victim doesn’t pay the ransom demand, then the Maze operators and other malicious groups threaten to expose the data, making the event a reportable data breach as well. Maze was also the first group to include a press release on their dark web site to announce the victimized organizations. Between the threat of not recovering their encrypted files and the additional concerns of data breaches, government fines, and lawsuits, most companies feel compelled to pay the ransom and malicious actors are betting on that. Double extortion schemes increased by 59% in 2020 and the trend is only growing in 2021.[15] Since 2019, over 2,100 organization have had data stolen and posted online after a ransomware attack by at least thirty-four of the most sophisticated ransomware gangs. Of these operations, at least 266 leaks were posted by the Maze group, 338 by Conti, and 222 by REvil.[16]

In February 2021, the U.S. Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center (FS-ISAC) announced that, in 2020, more than 100 financial services firms across multiple countries were targeted in a wave of ransom distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks conducted by the same malicious actor. That malicious actor methodically moved across jurisdictions in Europe, North America, Latin America, and the Asia Pacific, targeting the full gamut of financial services companies, including consumer banks, exchanges, payments companies, card issuers, payroll companies, insurance firms, and money transfer services. In each instance, the criminals sent extortion notes threatening to disrupt the firms’ websites and digital services with a DDoS attack if the demanded ransom was not paid.[17]

In January 2021, Microsoft became aware of critical vulnerabilities in the on-premise version of its Exchange Server product that is used for email, calendar, and collaboration solutions. In March 2021, Microsoft released software updates to address these critical vulnerabilities. Yet, as soon as the vulnerabilities were publicly announced, malicious actors began trying to outpace corporate patch management by scanning the entire internet for vulnerable Exchange servers and targeting hundreds of thousands of organizations in the United States, Asia, and Europe. Companies fell victim to this compromise and lost sensitive business information including intellectual property and, in some cases, had their business operations disrupted. To make things worse, two weeks after the patch was made available, the Black Kingdom ransomware gang and other malicious actors also began exploiting still unpatched Exchange servers. The Black Kingdom group first gains access to a corporate network, performs some reconnaissance, and then starts its encryption, leaving behind a nifty ransom note entitled “decrypt_file.txt” to announce their return. It provides explicit instructions on how to contact them, the ransom amount demanded, the Bitcoin wallet ID to use, and a message stating that they exfiltrated data from the corporate network. The note also states that refusal to pay would lead them to publish the attack and stolen files on social media.[18]

In March 2021, Taiwanese electronics and computer manufacturer Acer was infected with the REvil/Sodinokibi ransomware. The malicious actors demanded $50 million in Monero (a digital currency that is secure, private, and untraceable) — the highest known ransom demand to date — to provide a decryptor, a vulnerability report, and proof of deletion of stolen files. They posted images of the alleged stolen files, including financial and bank information, on their website as proof, and threatened to double the ransom demand if Acer didn’t pay by the deadline. Security researchers believe the malicious actors exploited an unpatched Microsoft Exchange server on Acer’s domain to execute the ransomware.[19] Of note, the REvil group also operates a RaaS business, offering material support to other “affiliates” who handle the technical details of the attack. The affiliate partners launch the initial infection, erase backups and exfiltrate the files (REvil affiliates get 70-80% of the ransom). REvil develops and delivers the target specific encrypted and ransom negotiates the ransom payment.

Yet, the ransom event that changed the risk calculus for many corporations occurred in July 2020, when the fitness brand Garmin suffered a worldwide outage of its systems. The Evil Corp. gang, a group linked to Russia, used the WastedLocker ransomware to successfully penetrate Garmin’s enterprise and knock it offline.[20] Garmin engaged Arete IR — an intermediary for negotiating ransom payments — and ended up paying $10 million to the criminals to restore its systems.[21]

Worth noting, however, is the fact that Evil Corp. and its principal operators are on the U.S. Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) list of Specially Designated Nationals (SDN)[22] for their role in developing and distributing the Dridex malware, used to conduct crimes against hundreds of banks and financial institutions in over 40 countries, causing more than $100 million in theft.[23] The Treasury Department performs a critical and far-reaching role in enhancing national security by implementing economic sanctions against foreign threats to the U.S., and paying ransom to criminal or terrorist organizations on their OFAC list can lead to fines and/or criminal offenses. When Garmin paid the Evil Corp. group — which Treasury considers a financial terrorist organization potentially acting for, or on behalf of, Russia — the company violated OFAC regulations.[24]

After the Garmin incident, the U.S. Treasury Department issued guidance to industry in October 2020, reminding them that “companies that facilitate ransomware payments to cyber actors on behalf of victims, including financial institutions, cyber insurance firms, and companies involved in digital forensics and incident response, not only encourage future ransomware payment demands but also may risk violating OFAC regulations… OFAC has imposed, and will continue to impose, sanctions on these actors and others who materially assist, sponsor, or provide financial, material, or technological support for these activities.”[25]

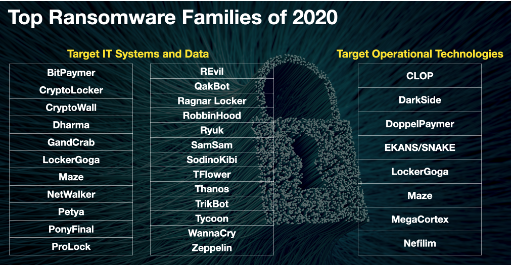

There are hundreds of different ransomware organizations or families targeting our institutions. These transnational syndicates are not just hijacking our IT systems but they are also targeting the corporate operational technologies that deliver citizens’ essential services, like the distribution systems of water and oil and gas.

In 2019, Temple University began cataloging Critical Infrastructures Ransomware Attacks (CIRWAs), based on publicly available information. Between November 2013 and March 2021, they tallied more than 907 such events.[26] Attacks that affect critical infrastructures risk can have debilitating effects on the country’s ability to function. The incidents against critical services have increased in frequency and severity over the last two years, and data reveals that around five critical infrastructure ransomware attacks occur every week on average.[27]

In February 2020, a natural gas compression facility fell victim to ransomware that impacted its pipeline operations and forced the plant to shut operations for two days. The malicious actor used a phishing email to infect the corporate networks and move laterally to operational networks, while the company lost visibility of assets and operations and was no longer able to read and aggregate real-time operational data. The incident also halted operations in the different geographically distinct compression facilities because of pipeline transmission dependencies.[28]

The Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack resulted in the exfiltration of nearly 100 gigabytes of data from the corporate networks in support of a double extortion scheme, in addition to the disruption of fuel distribution along the East Coast.[29] Colonial Pipeline is the largest refined fuel pipeline network in the country, transporting over 100 million gallons per day or roughly 45% of the fuel consumed on the East Coast of the United States, and is the main conduit of refined gasoline, diesel fuel, and jet fuel from the Gulf Coast up to New York Harbor and New York’s major airports. The incident throttled gas supplies across the easter U.S. for at least a week, causing a surge in fuel prices and impacting fuel supply in the Southeast and Central Atlantic markets. It forced the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Department of Transportation (DoT) to declare a regional state of emergency for 18 states to keep fuel supply lines open. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo stated that the government was “working closely with the company, state and local officials, to make sure that they get back up to normal operations as quickly as possible.”[30] President Biden invoked emergency powers to ensure oil and gas supplies kept flowing to big cities and airports along the East Coast, while Colonial continued to work to bring its pipeline back online in stages and “only when we believe it is safe to do so, and in full compliance with the approval of all federal regulations.” This was the most significant, successful attack on energy infrastructure in the U.S. to date. This event highlights the vulnerability of core infrastructures of the U.S. and demands a more forceful response.

Unfortunately, many victim entities choose to pay the ransom, for three principal reasons: (1) they have inadequate business continuity/disaster recovery processes and cannot restore their systems and, therefore, (2) they must pay the ransom to restore business-critical systems and data sets. Lastly, due to the growing number of data protection and privacy laws, such as Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), and the new California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), (3) companies fear having to pay the fines associated with data loss or for negligence in implementing security controls and would rather pay the extortionist to “promise not to post” about the incident in order to avoid paying the regulatory penalties for non-compliance.

Countries with a long record of hostility against the United States — China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea, among others — often benefit from ransomware attacks that can cripple U.S. organizations and critical infrastructures. The most sophisticated ransomware groups, including Iran’s Charming Kitten, North Korea’s Lazarus Group, Russia’s REvil Corp., and China’s APT27 and Winnti,[31] appear to have protection from their state that offers them a safe haven so long as they give a kick-back or act as proxies in other cyber operations. These loosely affiliated criminal groups often develop a symbiotic relationship with the state — intermittently working together for mutual benefit. The states can leverage these non-state actors (proxies) and their technical expertise and cyber capabilities to commit internationally wrongful acts using ransomware and other malicious software, without having to take responsibility.[32]

What Can Be Done?

The Role of Organizations. Organizations must recognize that the digital assets (software and hardware) that underpin their networks are commodities that have a shelf life that averages five to ten years. At the end-of-life of the commodity, the software/hardware product or service no longer receives the support of updates (that often remedy vulnerabilities) by the original manufacturer. Countless institutions are running legacy or unsupported products and services in their environments and are, therefore, vulnerable to exploitation. Moreover, for those digital assets that are supported with software/hardware updates, it is essential that organizations promptly update their systems when new updates (patches) are released. The so-called “Patch Tuesday” is inevitably followed by a “vulnerable Wednesday” — where malicious actors, who are now also aware of those newly disclosed vulnerabilities, can exploit unpatched systems and steal sensitive data, knock businesses offline and, in some cases, destroy the IT systems that power hospitals, schools, businesses, and essential services.[33]

The Center for Internet Security (CIS) Top 20 Critical Security Controls (previously known as the SANS Top 20 Critical Security Controls) is a prioritized set of technical best practices that, if implemented correctly, should provide an effective defense”[34] Most successful intrusions into an organization often occur because the organization has not implemented these basic controls. Organizations have largely been complacent about their responsibility to secure their digital assets and data sets. In fact, when insurance company American International Group (AIG) conducted an evaluation of the organizations that made cybersecurity policy claims in 2020, it found that at least 70% of those organizations did not have the appropriate controls in place.[35] Due to the frequency and severity of the ransom claims made in 2020 to insurance companies, AIG evaluated the control failures and prioritized 25 controls that it will seek organizations to have in place in order for AIG to underwrite a future policy. Many of these controls map directly to the CIS Top 20, which have been available for over a decade. At the top of AIG’s list are questions like: What is the applicant’s target time to deploy critical patches and what is the applicant’s year-to-date compliance with its own standards? Does the applicant maintain visibility and protect its end-point systems using behavioral-detection and exploit mitigation capabilities (e.g., desktops, laptops, mobile devices)? How does the applicant protect privileged credentials, and how and to what extent is the applicant dependent on Microsoft’s Active Directory for identity, access, authentication, and administration of the networked environment? Other important factors for evaluating an organization’s preparedness to minimize ransomware risks include whether the organization conducts regular backups of data, system images, and configurations; whether it tests backups, and keeps the backups offline; whether the organization knows its mean-time-to-recover from an incident and whether that is acceptable in terms of its risk appetite.

The Role of Insurance. The insurance industry has an important role in demanding and encouraging organizations to invest in the basic digital defenses of their networks and data. Yet, the insurance marketplace for cybersecurity policies still covers less than 30% of insurance policies underwritten so far, and this number may not reflect claims arising from cyber incidents that are submitted under non-cyber insurance policies. Regulators, like the New York State’s Department of Financial Services (DFS), have argued that the insurance market may “fuel the vicious cycle of ransomware” because some victims are specifically being targeted because they have [cyber] insurance.”[36] This may be an unfair claim, but nonetheless, the industry has seen a state change, where from early 2018 to late 2019, the number of insurance claims arising from ransomware increased by over 180%, and the average cost of a ransomware claim rose by 150%.[37] In 2020, the numbers were much higher and the average ransom demand is now in the tens of millions of dollars

In February 2021, Moody’s Investors Service Inc. reported that “a challenge for insurers is the potential for risk accumulations given that the same event can affect multiple policyholders across geographies and industries.”[38] These “ripple” claims can become very costly to the insurance industry. For example, one event can accelerate risk to many other organizations, like in the case of the thousands of vulnerable Microsoft Exchange servers that went unpatched and were exploited by nations and transnational organized crime syndicates in March and April 2021. An event like this could result “in multiple – theoretically, tens of thousands – of companies making insurance claims to cover investigation, legal, business interruption and possible regulatory fines.”[39] A similar event occurred in February 2021, when malicious actors exploited a critical software vulnerability found in the legacy large file transfer product made by software company Accellion. Despite the patch released by Accellion, at least 25 of its customers “suffered significant data theft” as a result of the compromise.[40]

A CISA joint advisory, published in conjunction with the cybersecurity authorities of Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and the United Kingdom, said that the malicious actors had targeted “multiple federal, and state, local, tribal, and territorial government organizations as well as private industry organizations in the medical, legal, telecommunications, finance, and energy fields.”[41] In at least some cases, the Clop ransomware group that exploited vulnerabilities in compromised Accellion appliance contacted victim organizations attempting to extort money to prevent public release of the stolen data. Victimized organizations included the supermarket chain Kroger, cybersecurity firm Qualys, Canadian airplane manufacturer Bombardier, Singapore’s largest telecommunications company Singtel, Australia’s Transport for New South Wales, Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (the country’s central bank), and many more.

The combination of ripple claims and the frequency of ransomed victims are squeezing the industry to increase insurance rates between 20-30% and decrease the market’s capacity.[42] AIG and other insurers are reviewing their portfolios and instituting a higher standard for underwriting policies, which should lead to improved digital risk management and fewer victims.

The Role of Government. The government also must do its part but, to date, many government institutions keep pointing the responsibility back to industry. In February 2021, the National Cyber Investigative Joint Task Force (NCIJTF) released a fact sheet on current threats posed by ransomware and mitigation strategies and measures that organizations should take to de-risk their chance of becoming a victim.

Nonetheless, there are many steps the government should still undertake. First, the U.S. Department of the Treasury OFAC should expand its list of Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) to include as many of the ransomware gangs as possible. Of course, this will require support from the intelligence and law enforcement communities, but if we want to stop the flow of ransom payments to our adversaries and their proxies, these malicious actors must be clearly identified and named, so that authorities can begin to impose real costs and consequences.[45]

Second, the U.S. Department of Justice should determine and make clear that paying a ransom is illegal. This step would likely force organizations to further invest in their security and ability to withstand and recover from an incident (i.e., increase their resilience). Categorizing ransom payment as an illegal activity would also clearly remove coverage for these types of payments from insurance policies. Third, the parallel “epidemic” of ransomware attacks should be systematically and operationally dismantled, which requires the government to treat it like terrorism — working operationally across all government agencies and with its international partners. The government has shown that it can track transnational networks, follow their illicit finance, and prevent malicious activities before they can cause harm to society. This type of crime should be no different. These ransomware syndicates work for themselves and for nations as proxies. They have sophisticated services to launch their malicious attacks (ransomware as a service) and rely on infrastructures to turn their cryptocurrencies into cash. Supporting sustained operations that take down their servers of service and monitor and eliminate the cryptocurrency exchanges that launder their money would be a strong beginning.

Lastly, policymakers should prioritize identifying who is backing — or ignoring — these syndicates that are holding our institutions hostage with ransomware. U.S. Representative Jim Langevin recently stated that “if the international community can identify areas where a country is clearly looking the other way and it has a concentration of bad actors and they’re not doing enough to shut down these bad actors, there’s a role for international, multi-nation efforts to hold nations accountable.”[46] If governments around the world began to treat ransomware organizations similar to how they treat terrorist organizations, then a higher priority may be placed on dismantling their operations and refraining from harboring their activities in sovereign territories.

Conclusion

Hospitals, schools, businesses, critical services, and infrastructures are being hijacked by ransomware — rendering their systems and data inaccessible and inoperable. The individuals, groups, and countries conducting these activities are employing intimidation and coercion tactics like terrorists would do and preying on victims’ fears — fear that a hospital will have to turn away patients, or that a school cannot conduct learning activities, or that a corporation cannot deliver a critical product or service, or that critical infrastructure could be irreparably disrupted (serious physical damage), or that an organization may not be able to deliver an essential service to its customers/citizens. The fear goes beyond business disruption, it includes the fear that the malicious actor will expose protected data (e.g., personally identifiable information, protected health information, proprietary information, etc.) and thereby activate a regulatory penalty and possibly reputational damage.

Our corporations and civic institutions are literally paying our adversaries (and their proxies) to restore their network’s functions and data back to normal. It should be obvious that the U.S. and its allies need to know the full extent of the threat and understand how much money is being paid and to whom — whether directly or indirectly. The U.S. and its allies know how to dismantle terrorist networks and therefore should apply this know-how to systematically and operationally take down ransomware networks, the services that they provide to other criminals, and the operators’ ability to extort vulnerabilities for money. This requires a sophisticated, coordinated, transnational approach, where many entities have roles to play and responsibilities to fulfill. Ransomware activities should no longer be allowed to disrupt civil order, coerce organizations into paying large ransom demands, and threaten the economic prosperity, safety, and security of the United States and its allies. The U.S. government has identified the growing threat of ransomware as an epidemic causing grave harm to society; now, they should name the ransom operators as terrorists and neuter their ability to cause harm.

Endnotes:

[1] U.S. Department of Justice, “How to Protect Your Networks from Ransomware,” https://www.justice.gov/criminal-ccips/file/872771/download.

[2] Check Point Research, “Global Surges in Ransomware Attacks,” https://blog.checkpoint.com/20…, and “Cyber Security Report 2021,” https://www.checkpoint.com/dow….

[3] Lily Hay Newman, “A Ransomware Attack Has Struck a Major US Hospital Chain,” WIRED, 28 September 2020, https://www.wired.com/story/un….

[4] Jessica Davis, “UPDATE: UHS Health System Confirms All US Sites Affected by Ransomware Attack,” Health IT Security, 5 October 2020, https://healthitsecurity.com/n….

[5] Lucien Constantin, “Ryuk ransomware explained: A targeted, devastatingly effective attack,” CSO Online, 19 March 2021, https://www.csoonline.com/article/3541810/ryuk-ransomware-explained-a-targeted-devastatingly-effective-attack.html.

[6] Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) Alert, “Ransomware Activity Targeting the Healthcare and Public Health Sector,” 28 October 2020, https://us-cert.cisa.gov/ncas/….

[7] DataBreaches.Net, “Broward County Public Schools Cyberattack was Ransomware Attack — New Details Emerge,” 27 March 2021, https://www.databreaches.net/b….

[8] Steve Zurier, “Conti ransomware gang hits Broward County Schools with $40M demand,” SC Magazine, 2 April 2021, https://www.scmagazine.com/hom…, and Terry Spences and Frank Bajak, “Large Florida School District hit by Ransomware attack,” Associated Press, 1 April 2021, https://sports.yahoo.com/large….

[9] “Hackers Post Files After Broward School District Doesn’t Pay Ransom,” NBC Miami, 20 April 2021, https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/….

[10] Ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) is a platform designed to enable someone with very little know-how about malware, code, or cyber attacks, to conduct a ransomware attack and turn a profit. RaaS is designed to operate with a user-friendly platform that allows the attacker to simply pick their victim, set the ransom, pick a payment deadline and bitcoin wallet address, and deploy a ransomware variant. The developers of many RaaS platforms take a percentage of whatever the attacker is paid.

[11] Federal Bureau of Investigation, “FBI-Flash: Increase in PYSA Ransomware Targeting Education Institutions,” 16 March 2021, https://www.ic3.gov/Media/News….

[12] Office of Communication and Community Relations, “Update on Cybersecurity Incident,” FCPS Blog, 9 October 2020, https://www.fcps.edu/blog/upda….

[13] BitDefender, “2020 Consumer Threat Landscape Report, https://www.bitdefender.com/fi….

[14] Federal Bureau of Investigation, “FBI Flash: Mamba Ransomware Weaponizing DiskCryptor,” 23 March 2021, https://www.ic3.gov/Media/News….

[15] IBM Security, “X-Force Threat Intelligence Index,” 2021, https://www.ibm.com/downloads/….

[16] The most sophisticated ransomware gangs that employ double extortion schemes include Team Snatch, MAZE, Conti, NetWalker, DoppelPaymer, NEMTY, Nefilim, Sekhmet, Pysa, AKO, Sodinokibi (REvil), Ragnar_Locker, Suncrypt, DarkSide, CL0P, Avaddon, LockBit, Mount Locker, Egregor, Ranzy Locker, Pay2Key, Cuba, RansomEXX, Everest, Ragnarok, BABUK LOCKER, Astro Team, LV, File Leaks, Marketo, N3tw0rm, Lorenz, Noname, and XING LOCKER.

Lawrence Abrams, “Ransomware gangs have leaked the stolen data of 2,100 companies so far,” Bleeping Computer, 8 May 2021, https://www.bleepingcomputer.c….

[17] FS-ISAC, “More than 100 Financial Services Firms Hit with DDoS Extortion Attacks,” 9 February 2021, https://www.fsisac.com/newsroo….

[18] Dan Goodin, “Ransomware operators are piling on already hacked Exchange servers, Ars Technica, 23 March 2021, https://arstechnica.com/gadget…, and Steve Ramey, “Black Kingdom Returns to Exploit Zero-Day Vulnerabilities in Unpatched Microsoft Exchange Servers, Arete, 22 March 2021,

https://www.areteir.com/black-….

[19] Steve Zurier, “Microsoft Exchange exploit a possible factor in $50M ransomware attack on Acer,” SC Magazine,22 March 2021, https://www.scmagazine.com/hom…, and Lawrence Abrams,”Computer giant Acer hit by $50 million ransomware attack,” Bleeping Computer, 19 March 2021, https://www.bleepingcomputer.c….

[20] Lawrence Abrams, “Confirmed: Garmin received decryptor for WastedLocker ransomware,” Bleeping Computer,1 August 2020, https://www.bleepingcomputer.c….

[21] Tim Starks, “US advisory meant to clarify ransomware payments only spotlights widespread uncertainty, CyberScoop, 13 October 2020, https://www.cyberscoop.com/ofa….

[22] The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the US Department of the Treasury administers and enforces economic and trade sanctions based on US foreign policy and national security goals against targeted foreign countries and regimes, terrorists, international narcotics traffickers, those engaged in activities related to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and other threats to the national security, foreign policy or economy of the United States.

[23] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Sanctions Evil Corp, the Russia-Based Cybercriminal Group Behind Dridex Malware,” 5 December 2019, https://home.treasury.gov/news….

[24] Jeff Stone, “U.S. charges two Russians in connection with Dridex banking malware,” CyberScoop, 5 December 2019, https://www.cyberscoop.com/dri….

[25] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “ Advisory on Potential Sanctions Risks for Facilitating Ransomware Payments,” 1 October 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/syst….

[26] Temple University, “Critical Infrastructure Ransomware Attacks,” https://sites.temple.edu/care/….

[27] SentinalOne Blog, “How Ransomware Attacks Are Threatening Our Critical Infrastructure,” 17 September 2020, https://www.sentinelone.com/bl….

[28] Dan Goodin “US natural gas operator shuts down for 2 days after being infected by ransomware,” Ars Technica,18 February 2020, https://arstechnica.com/inform…, and DHS CISA Alert, “Ransomware Impacting Pipeline Operations,” 18 February 2020, https://us-cert.cisa.gov/ncas/….

[29] Jordan Robertson and William Turton, “Cyber Sleuths Blunted Pipeline Attack, Choked Data Flow to Russia,” Bloomberg, 10 May 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news… .

[30] CBS News, “Transcript: Secretary Gina Raimondo on ‘Face the Nation’,” 9 May 2021, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/t… .

[31] Phil Muncaster, “Chinese APT Group Linked to Ransomware Attacks,” InfoSecurity Magazine, 5 January 2021, https://www.infosecurity-magaz….

[32] Office of the Director of National Intelligence, “Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community,” 9 April 2021, https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI… .

[33] Melissa Hathaway, “Patching our Future is Unsustainable and Dangerous, CIGI Paper No. 219, June 2019,https://www.cigionline.org/art….

[34] Center for Internet Security, “The 20 CIS Controls & Resources,” https://www.cisecurity.org/con….

[35] Author’s interview with Tracie Grella, Global Head of AIG Cyber Insurance, 12 February 2021.

[36] NY Department of Financial Services, “Cyber Insurance Risk Framework,” 4 February 2021, https://www.dfs.ny.gov/industr….

[37] NY DFS Cybersecurity Regulation 2020, Cyber Survey of reported events (See 23 NYCRR 500.17).

[38] Claire Wilkinson, “Cyber insurance prices increase on ransomware claims: Moody’s,” Business Insurance, 5 February 2021, https://www.businessinsurance…..

[39] Continuity Insurance & Risk, “MS Exchange attacks could lead to thousands of insurance claims,” 26 March 2021, https://www.cirmagazine.com/ci….

[40] Accellion, “Update to recent FTA security incident,” 1 February 2021, https://www.accellion.com/comp….

[41] DHS CISA, “CISA Releases Joint Cybersecurity Advisory on Exploitation of Accellion File Transfer Appliance,” 24 February 2021, https://us-cert.cisa.gov/ncas/….

[42] Judy Greenwald, “Cyber insurance rates to increase 20-50% this year: Aon,” Business Insurance, 4 March 2021, https://www.businessinsurance…..

[43] “Ransomware - What it is & What to do about it,” https://www.ic3.gov/Content/PD….

[44] Maggie Miller, “DHS Secretary Mayorkas announces new initiative to fight ‘epidemic’ of cyberattacks,” The Hill, 25 February 2021, https://thehill.com/policy/cyb….

[45] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Office of Foreign Assets Control - Sanctions Programs and Information,” https://home.treasury.gov/poli….

[46] Shannon Vavra, “New global model needed to dismantle ransomware gangs, experts warn,” CyberScoop, 17 March 2021, https://www.cyberscoop.com/ran….