As the world turns upside down, Mariana Mazzucato discusses how to shape an economy that works for everyone

Mariana Mazzucato, Professor of the Economics of Innovation at the Science Policy Research Unit of the University of Sussex and author of The Entrepreneurial State: debunking public vs. private sector myths, has made a passionate case for the government’s active role in the economy —sending the old laissez faire notion that markets can run themselves into the dustbin where it belongs. In a new book co-edited with Michael Jacobs, Rethinking Capitalism: Economics and Policy for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth, she offers a bold new vision for contemporary capitalism that works for the people and the planet. What chance does this vision have in the age of Trump and Brexit? Mazzucato shares her view.

Lynn Parramore: The new book is called “Rethinking Capitalism.” What aspects of capitalism do you think were most responsible for recent political shifts, like Brexit and the election of Donald Trump?

Mariana Mazzucato: In the book, we set out various failures in the model of capitalism that has dominated the last three decades — from instability of growth to increasing inequality to the threats of climate change. We argue that these failures are connected to failures of economic thinking.

Effects of these failures on the electorates of the U.S. and the U.K. are fairly well documented, and some – such as the inability to deliver growth that includes everyone – have now become electorally significant. Growth in productivity has diverged from growth in the share that working people can expect right across advanced economies, but this trend started earlier and has been more pronounced in the U.S.

To give you some stats, real median household incomes in the U.S. were basically the same in 1989 as in 2014. But we are also seeing similar challenges in the U.K. in the stagnation of real wages. Recent analysis from the U.K. Institute for Fiscal Studies suggests that wages will still be below 2008 levels in 2021. People work hard and companies make big profits, but employees don’t see that they share in the wealth they help to create.

For too long, these problems have been ignored. And the results of the U.S. election and the EU referendum showed that people were no longer willing to vote for the status quo.

Where there is less agreement is on the reasons why. It would be a mistake to overstate the similarities between the Brexit vote and Trump’s win – but there are common themes, not least in the rallying cries that the winning campaigns used. They focused on a supposed economic threat posed by outsiders – as immigrants or as trade partners. This fuelling of anxieties underpinned a narrative centered on the need to “regain control,” whether of borders or of economic forces. Unfortunately, simplistic framing of the problems leads to simplistic answers.

Another similarity of Brexit and Trump’s campaigns was an attack on so-called ‘elites.’ This is not so much a failure of capitalism as of its high priests in the economic profession – for which we must all take some responsibility.

LP: So what’s the real story of what’s not working for so many?

MM: If we look at the complexity of the challenges facing western societies today, we see that the problems are not really about outsiders, but have their roots much closer to home.

Our current model of capitalism and the dominant ideas in policy making have led to a failure of investment by both the public and the private sector in the things that drive productivity, and which affect its distribution. Shareholder value theory — the destructive idea that companies should be run solely for the benefit of shareholders — has led to financialized businesses that do not invest in the areas that will lead to future growth or the invention of useful new products. Companies prefer to put money in the pockets of shareholders or to hoard cash rather than to raise wages or invest.

But it is not just how these ideas have affected the private sector. They have also had a detrimental impact on our understanding of the role government can play in raising both the rate of growth and shaping its direction. Mainstream economic theories popular in the last several decades have tended to downplay the government’s role in markets and to increase skepticism about even that more limited role. Austerity, particularly in Europe, has added to the problem. It has not worked, even on its own terms.

LP: In your earlier book, The Entrepreneurial State, you describe a model of capitalism that would address many of these problems. How does it work?

MM: My work has shown how a different understanding of the role of the state in growth can unlock private investment. Markets are not static entities that are ‘intervened’ in (for good or bad) but are outcomes of public and private interactions. In my view, the state should be active and work in cooperation with private businesses to spur growth that’s sustainable and inclusive. The policy process is about co-creating and co-shaping of markets, creating new opportunities for business investment —and negotiating a better deal for the public too.

Historically, it has been an entrepreneurial state that stimulates and gives direction to new technological opportunities. It is those opportunities that stir the animal spirits of business to invest—and we can do that again. The examples I give in my book show that public investments are not only important for affecting the rate of growth but also its direction. And that these investments were most successful when mission driven, rather than aimed at single sectors. The venture capital industry entered biotechnology only decades after the National Institutes of Health led the way. Similarly, Apple’s i-products were only made possible due to the hefty public financing of all the technologies that make those products smart and not stupid: internet, GPS, touchscreen and SIRI. Today there are opportunities in green: indeed Germany is using its Energiewende policy as a way of envisioning a green transformation and innovation across many sectors.

If we want growth today to be more innovation-driven, more inclusive and more sustainable, then we need a more active state — not a less active one. Yet we still hear the dogma that we should just fix market failure by focusing on science and infrastructure, and to ‘level the playing field.’

Fixing markets isn’t enough. We have to actively shape and create them and ‘tilt’ the playing field in the direction of the growth we want.

LP: What’s your impression of the possibilities to get things moving in a better direction in the wake of recent political shifts?

MM: Brexit and Trump have brought the problems of capitalism into sharp relief, but both are only making things worse. Take the investment challenge – businesses invest where there they see technological or market opportunity. Brexit has shrunk the market opportunities. Exiting trade deals will do the same for the U.S. Those deals must be actively shaped and governed to make growth more inclusive.

But – to look on the bright side – because the problems are now in greater focus and can no longer be pushed aside, maybe policy makers will be more creative in trying to address them.

I see signs of that, for example, in Theresa May’s explicit embrace of industrial strategy, with a seeming interest in focusing this on missions that help make a better society, which I’ve discussed recently with various people in the government. There is a lot of flesh to be put on the bones – but there is at least an opening for a more pragmatic, less ideological debate about how to build economies that work for people, within the limits of our planet.

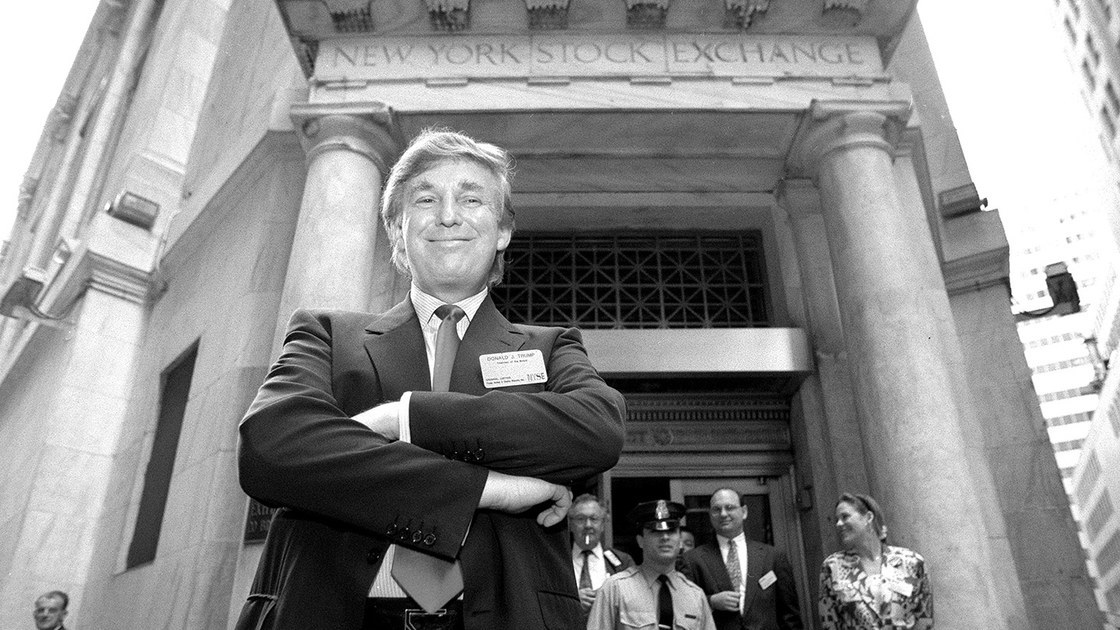

With a Trump administration we don’t know enough yet to make predictions, but if past behavior is any indication, I am not encouraged. As I wrote in an article for the Guardian, as a businessman, Trump has been associated with some of the worst excesses of a particular style of value-extracting and asset stripping capitalism: set up businesses, let them fail, avoid paying suppliers, use bankruptcy laws to avoid taxes for decades, then set up another business somewhere else. It is this model that is the cause of many problems we see today.

LP: Trump seems to be rethinking fiscal policy with his proposal for an infrastructure program, which is interestingly a focus he shares with former candidate Bernie Sanders. What is your opinion of that focus?

MM: Too many politicians seem to reach for ‘infrastructure’ as the default answer to investment, as if roads and bridges were the answer to everything. Even the IMF and the World Bank seem to mainly offer infrastructure spending as an alternative to austerity, although they are right to focus on the need for investment.

While infrastructure is of course important, it must be part of a bigger vision. The point is not to simply dig ditches but to steer those investments towards transformational growth. We should be investing where the public returns are greatest – that is in innovation. If we look at Germany’s infrastructure policy, it has been driven by its mission-oriented focus on green infrastructure. This affects both innovation and infrastructure, old industries and new. The German steel industry, for example, has adapted to the policy by lowering its material content through a ‘repurpose, reuse and recycle’ strategy.

Added to this, my specific concerns with Trump’s plans are that they are likely to investments in infrastructure where the private returns are highest (for example toll roads and bridges) rather than where the public gains are greatest.

LP: Speaking of green, how have the stakes of rethinking the economics of climate change shifted with Brexit and Trump?

MM: Green is not just about renewable energy. It’s also about creating a new direction for the whole economy. This requires government to step up, not step back, creating the kinds of mission-oriented public organizations that will enable us to tackle climate change — as ambitious as those that got us to the moon. It also requires the financial sector to be less short-term since we know that short-term finance has distorted incentives and directions in areas like biotechnology.

A new study we are doing with data produced by Bloomberg New Energy Finance looks at the role of public banks and other public entities in providing the strategic, patient finance for the green revolution. An interesting attribute of public banks is that they don’t only de-risk the downside, but also get a share of the upside. This brings us to John Maynard Keynes’ idea of the ‘socialization of investment,’ which could provide new thinking on the types of public and private deals that the 21st century requires.

Brexit and Trump’s election are forcing countries to come up with new radical ideas. In this context, rethinking capitalism means rethinking the role of the public sector, the role of the private sector, the role of finance, and the relationship between them all. What is needed is both a New Deal in terms of mission-oriented investments but also a new deal in terms of a modern social compact—one that allows the state to socialize not only risks but also rewards. Maybe then innovation-led growth will also become growth that includes all of us.